Why, I ask Will Ferrell, does transphobia exist? He blinks, opens his mouth agape, and shakes his head. “I think we fear what we don’t know,” he replies, softly.

Ferrell is still getting used to questions like this. As a comedian and a movie star, he’s spent decades quietly existing behind a litany of absurd, fictional man-babies. As audiences, we have a handle on Anchorman’s Ron Burgundy, or Ricky Bobby from Talladega Nights, or Buddy from Elf – big, flashy creations who whine and wonder and peacock. The man behind all of it, though, is more of a question mark. Think about it. Do you have any idea of Will Ferrell’s personal life and politics? So, when asked about the state of the world – and not, as he usually is, about whether there’ll ever be a Step Brothers sequel – he speaks slowly, deliberately and carefully. A funny man with his serious hat on.

I’m asking Ferrell about transphobia because of a new documentary, Will & Harper, named after the actor and his best friend of nearly 30 years, the comedy writer Harper Steele. In 2022, at the age of 61, Steele sent Ferrell a letter in which she told him she is trans, and was newly in the process of transitioning. “I just ask you as my friend to stand up for me,” Steele wrote. “Do your best to, if I’m misgendered, just speak up on my behalf, that’s all I ask.”

Steele didn’t know what her loved ones would think, or the extent to which she’d be treated differently by them. She was also worried about America – before she transitioned, she’d often travel the country and venture to parts unknown, stumble upon the grimiest of far-out dive bars, and make friends with total strangers. Would this no longer be possible? In search of answers, she and Ferrell decided to hit the road together, taking along with them the filmmaker Josh Greenbaum. The result, a touching if melancholy snapshot of friendship and queerness, is streaming on Netflix from Friday.

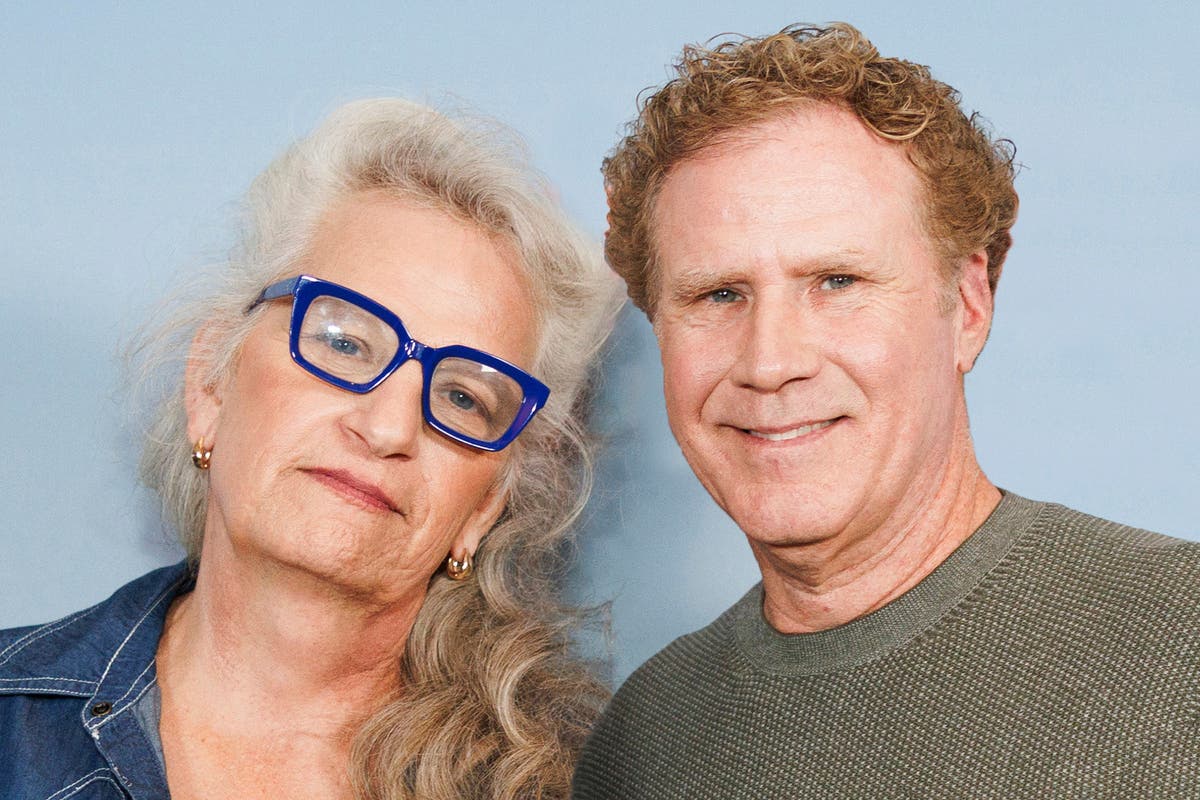

“We met a lot of people who were just…” Ferrell searches for the right phrase, glancing over at Steele. He finds it. “Who were just… ‘You do you – you’re not a threat.’” The three of us are sitting in a London hotel suite, Ferrell dressed in a grey knit jumper, Steele in a pink blouse accessorised with pearls. She wears multicoloured spectacles, and her hair is a flood of cascading white waves.

“There is hatred out there,” Ferrell continues. “It’s very real and it’s very unsafe for trans people in certain situations.” He ponders my original question. “But I don’t know why trans people are meant to be threatening to me as a cis male. I don’t know why Harper is threatening to me.” The pair have a gentle rapport – there are lots of appreciative smiles back and forth. “It’s so strange to me, because Harper is finally… her. She’s finally who she was always meant to be. Whether or not you can ultimately wrap your head around that, why would you care if somebody’s happy? Why is that threatening to you? If the trans community is a threat to you, I think it stems from not being confident or safe with yourself.”

I first tend to ask reporters who interview me if they believe in me. Do they believe that I exist? That I’m valid? Because there are many people in the liberal community who can’t seem to get their heads around it for one reason or another

Harper Steele

Ferrell seems to clock the seriousness in the room. “Well, that’s my lame answer,” he deadpans. He and Steele laugh. “It was a good one,” Steele says. “You should write a paper on it.”

Ferrell and Steele met in 1995 when they were hired for the venerated US sketch show Saturday Night Live – Ferrell as a performer, Steele as a writer. They quickly found each other. “There were a lot of personalities competing for airspace,” Ferrell remembers. “And when I see that, I tend to just pull back.” He got a bit of a reputation. “People were like, ‘Hey, has anyone met that tall guy? He’s pleasant but he doesn’t seem that funny.’”

Steele, though, had noticed him. They had a similar sense of humour, favouring off-the-wall, experimental comedy, which they’d later infuse into the sketches they wrote together. “I found out later that, unbeknown to me, she’d been a mini-advocate of mine,” Ferrell says. “She’d been reporting back to the main bullpen of people, I guess, like, ‘That guy’s actually kind of funny!’” They ended up becoming close collaborators, both at SNL and beyond – Steele has written many of Ferrell’s more outré projects, among them the Spanish-language comedy Casa de Mi Padre and the Netflix hit Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“Comedy is their love language,” Greenbaum tells me later. “It’s the thing the two of them always dip into.” The filmmaker, best known for his zany buddy comedy Barb & Star Go to Vista Del Mar, had known Ferrell and Steele for years before Will & Harper, and hoped to honour the pair’s friendship on film. It meant the resulting work became a tonal rollercoaster, though – too comedic and the seriousness of Steele’s journey would get diluted; too heavy and you’d lose the innate levity of both of its stars. A running joke about different flavours of Pringles was kept in, for instance. An extended bit in which Ferrell was seen hiding in the air ducts of Washington’s International Spy Museum? Nixed.

Largely missing, too, is acknowledgement of the political climate into which the film is being released. There is one particularly wince-inducing scene in which Ferrell and Steele shake hands with a US politician at a basketball game in Indiana, only to find out later that he had voted for a raft of anti-trans legislation. But it’s an outlier in a film that prioritises the personal over the political.

“We were all aware that it would be received as a political film and brought into the political conversation,” Greenbaum says, “but at its core it’s a very pure, simple story of two friends. I think more hearts and minds can be changed and affected by that. In the climate we’re in now, if you smell an agenda, or you sniff out that someone is trying to convince you of anything, you lose half the audience. In no sense were we trying to avoid politics, but it didn’t feel central to the story we were telling.”

Will & Harper is, fundamentally, a film of two halves. The most powerful half is related to Steele’s journey, as she unpacks years of private struggle and begins to piece together a new life. Then there is the presence of Ferrell, who very much serves as a surrogate for viewers at home who, even if completely unbothered by trans people, still might have questions about trans identity that are typically tiptoed around.

“It’d be disingenuous not to point out that we were aware of the reach that Will Ferrell has,” Greenbaum says. “The fanbase he has crosses all spectrums, but it also has a very traditionally straight, cis-male, bro-y [element]. On some level, for sure, we want to reach that audience. But it was very important to me, and to Harper, that we were also representing the queer community.”

In this, they succeeded – while watching Will & Harper, you are quickly reminded of how unusual it is to see trans people actually talking about themselves rather than being talked about on the nightly news or by cisgender columnists. Even more unusual is watching two trans women converse about their respective transitions, as Steele does during one pitstop along the road.

I ask Steele, though, if she is happy with the movie’s vaguely apolitical stance. There’s no discussion, for example, of polite, liberal transphobia. In the UK and USA, at least, the most aggressive voices in anti-trans discourse are those of individuals who otherwise claim to be left-leaning. In Will & Harper, though, most of the transphobia both Steele and Ferrell are seen worrying about stems from rural pockets of middle America. Trump country, effectively. Is Steele conscious of the other kind?

“They’re in the background of my head, personally,” Steele says. “I’m certainly hearing that voice in my country. The New York Times is kind of the centre of that – generally left-leaning, but also sometimes very anti-trans. It’s odd…” She trails off. “It’s why I first tend to ask reporters who interview me if they believe in me. Do they believe that I exist? That I’m valid? Because that’s not always part of the conversation. I like to start there. Because there are many people in the liberal community who can’t seem to get their heads around it for one reason or another.”

But Will & Harper, she says, wasn’t the movie for digging into that. “We just wanted to address what it’s like for two people who are friends – what all of this means to us, and to our friendship moving forward. I needed him to see the joy I was experiencing.” Steele breaks into a smile. “And I also wanted to demonstrate to my friend here that I was still funny,” she laughs. “And probably funnier than him.”

“Well,” Ferrell corrects, puffed up and mock-offended. “I think that’s debatable.”

‘Will & Harper’ is streaming on Netflix from 27 September