Imagine you’ve just awoken from a decade-long Rip Van Winkle-esque nap. The world around you seems unfamiliar, bafflingly so – what is this “Skibidi Toilet” all the kids are talking about? What the hell is a “TikTok”?? – but a few things remain the same. Leicester’s swaggering Brit-rock titans Kasabian are still touring, for example. But watching their Glastonbury appearance from this summer, you note the absence of OG frontman Tom Meighan. That flamboyant guitarist Sergio Pizzorno is now doing the singing. It is, to say the least, somewhat unsettling.

Groups rarely survive a change in singer, which is, of course, why groups rarely change their singer. Mark E Smith, acerbic frontman with post-punk institution The Fall, once addressed the systemic instability within their ranks – 60-odd members over their 42-year existence – with the deathless words: “If it’s me and your granny on bongos, then it’s a Fall gig.” Smith’s inference was uncharacteristically clear: the drummer, bassist, keyboardist, guitarist, keytarist and kazoo player are all expendable, but if you lose the bloke at the front with the microphone, it’s all over.

He had a point: it’s generally a bad sign when the singer goes awol. They’re a group’s literal voice, often the lyricist and always the front person – the band member who their fans most identify with, the focus for the media’s attention. But while Smith’s untimely 2018 passing sounded the death knell for The Fall, a number of groups – indeed, some of rock’s biggest legacy names – somehow survived their singer’s exit. And in some cases, they managed to enjoy even greater success in their new incarnation.

Take the horticulturally minded prog-rockers Genesis. Though their mission to awaken the world to the deadly threat of the Giant Hogweed won them a loyal following of men in shabby jackets (and absolutely no women whatsoever), singer/mime-enthusiast Peter Gabriel experienced a literal seven-year itch around the time his first daughter was born in distress and his bandmates’ reaction was to grumble: “Yes, but what about the next album?” Gabriel promptly exited the band for a life of world music, plasticine and Kate Bush duets, while the other fellers scrambled to advertise for a replacement.

After days of unsatisfying auditions, however, the remains of Genesis got desperate enough to consider the unthinkable: what if we let the drummer have a go? After all, sticksman Phil Collins had already sung on a couple of songs. They rolled the dice and, almost immediately, Collins – a soul-man in progster’s clothing – adulterated their setlist of complex epics about possessed musical boxes with ballads that lasted less than 10 minutes. As the Eighties dawned, Genesis began scoring actual chart hits and seeing actual human women in the crowd at their concerts, the group became an actual mainstream rock phenomenon.

As much a lurid soap opera as a band, bluesers Fleetwood Mac lost mercurial founding singer/guitarist Peter Green in 1970 when he suffered a severe breakdown after German hippies spiked him with some bad acid. The group’s other guitarists, Jeremy Spencer and Danny Kirwan, stepped into the breach (and bassist John McVie’s wife, organist/vocalist Christine, also hopped aboard), but the Mac microphone seemed as cursed as Spinal Tap’s drum stool.

In 1971, while on tour in the US, Spencer told his bandmates he was “popping out for a magazine” but instead absconded to join The Children of God, a religious sex cult. A year later, Kirwan announced his exit by smashing up his beloved Les Paul guitar before a show. Replacements were found: vocalist Dave Walker, who only lasted one album, and singer/guitarist Bob Weston, who convinced these Brits to relocate to his native Los Angeles, and then promptly resigned in 1974.

Lesser/saner outfits would have called it a day at this point, but the Mac persisted, hiring Californian singer-songwriters Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, whose folk-rock lightness-of-touch transformed the group. Incalculable success followed, along with a literal snowstorm of cocaine and the breakup of the McVies’ marriage. Buckingham and Nicks split up and Nicks engaged in a brief affair with drummer Mick Fleetwood (safe to say, this sort of thing never happened in Genesis).

But somehow, the marriage-of-convenience that was this incarnation of Fleetwood Mac lucratively held it together for decades, bar the occasional fractious hiatus, until Buckingham left for good in 2018 and the remaining members hired Neil Finn, singer/songwriter with Crowded House, to bolster them through a final farewell tour before Christine McVie, always the most stable member of the group (and arguably the finest singer they ever had) passed away in 2022, and Mick Fleetwood acknowledged they were finally “done”.

Sometimes the sudden exit of a singer presages a transition akin to a caterpillar becoming a butterfly. Check Deep Purple, who in the late 1960s were a psych-rock beat group straight out of Austin Powers’ wildest dreams, before the band realised pop was about to turn heavy and ditched founding vocalist Rod Evans. Rod, you see, was a mod, and therefore yesterday’s man once the new decade dawned, but their next singer – the leonine Ian Gillan – had a commanding, agile voice that would put Purple shoulder-to-shoulder with Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath.

Gillan fronted Purple for their biggest anthems, until workload-related exhaustion and tensions with guitarist Ritchie Blackmore forced his exit in 1973. He was replaced by cocksure Saltburn-born unknown David Coverdale, who took the band in a funkier direction, causing Blackmore himself to quit. Purple split in 1976, while Gillan returned for a 1984 reunion, only to be fired in 1989, and then rejoin again in 1993. Drummer Ian Paice is the only member to have been in every Purple lineup and will likely bury them all.

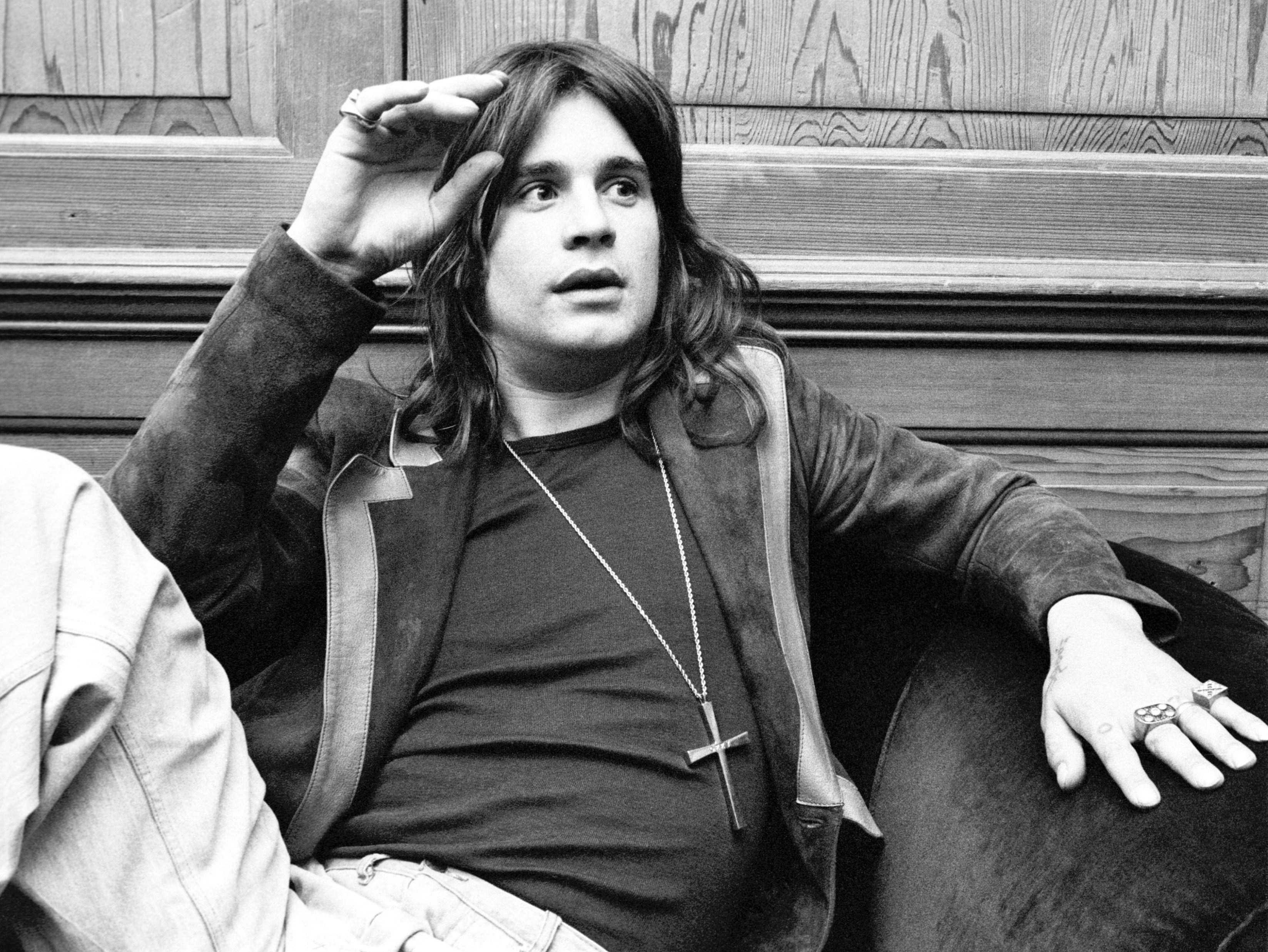

When the misadventures of the notorious OZZY, Ozzy Osbourne, proved too much for even his troublemaker bandmates in Black Sabbath, Oz was fired and went off to bark at the moon. The Sabs, meanwhile, tapped American Ronnie James Dio (formerly vocalist with Ritchie Blackmore’s post-Purple group Rainbow) whose voice was more unabashedly acrobatic than Oz’s. Many argue his records with Sabbath – 1980’s Heaven & Hell and 1981’s Mob Rules – revitalised that band. When he quit in 1982 to form his own band, Dio, the Sabs entered a hellish purgatory they wouldn’t escape until Ozzy’s return in 1997.

It does seem to be the heavy groups who are wont to switch singers mid-career – perhaps because they are often driven by a key instrumentalist, often the guitarist; perhaps because the big bands are larger-than-life franchises bigger than any single frontperson; and perhaps because the turbulent world of metal is more prone to what we euphemistically call “musical differences”.

I didn’t know what to do. I was terrified it might be over

Serge Pizzorno of Tom Meighan’s 2020 exit from Kasabian

Heavy contemporaries Judas Priest experienced a markedly less successful change of singers when leather-clad frontman Rob Halford ditched the group in 1992, perhaps burnt out by a ridiculous US trial, which saw the band accused of hiding “backwards-masked” messages in their music encouraging fans to kill themselves. The remaining members of Priest cast around for a new singer for months, eventually settling on then-unknown Tim “Ripper” Owens, frontman for Judas Priest tribute band British Steel. Though the band’s single “Bullet Train” was nominated for a Grammy, Owens’ tenure with Priest was largely a bust, and is today best remembered for inspiring the uninspiring Mark Wahlberg movie Rock Star – of which Owens said: “If I could sue, I would”. Owens now sings in ex-Priest guitarist KK Downing’s new band, KK’s Priest. Happily, Halford returned to Judas Priest in 2003; the band embarked on a world tour to celebrate.

In more current heavy-music news, nu-metal pioneers Linkin Park – who had been on hiatus following the 2017 suicide of frontman Chester Bennington – have returned to the stage and have a new album on the way, with founding guitarist/vocalist Mike Shinoda now joined by new member Emily Armstrong, also of the group Dead Sara. The appointment hasn’t been uncontroversial, however, and the band have received flak for Armstrong’s support for actor Danny Masterson, who was convicted of rape in 2023, for which she has since apologised.

As for Kasabian, whose tour begins on 8 November in Birmingham, they shed Meighan in 2020 shortly before he pled guilty to assaulting his fiancée. “I didn’t know what to do,” said guitarist and founder Serge Pizzorno recently, of the traumatic days surrounding the singer’s exit. “I was terrified it might be over.” However, the continued support of Liam Gallagher, who has tapped the group as a regular support act, emboldened them, and their 2022 comeback album The Alchemist’s Euphoria and this summer’s follow-up Happenings were among the group’s most critically acclaimed releases, both topping the UK albums chart.

These records pair the dextrous anthemicism of old with a more adventurous sonic approach, swinging from melancholic widescreen disco (“Darkest Lullaby”) to thrashy punk scrapping (“How Far Will You Go”) and experimental art-rock preening (“Bird in a Cage”) with a confidence that belies a few shaky years for the group. As a vocalist, Serge is a revelation, slicing away the workaday blokeishness that Meighan occasionally stumbled into, and clearly relishing having the driving seat to himself. Following in the footsteps of giants – and wisely avoiding hiring from the ranks of their own tribute acts – Kasabian are enjoying their career’s epic second act.