Ed Ram/Getty

Ed Ram/GettyA humanitarian crisis is unfolding in the north of Ethiopia, driven by drought, crop failure and continued insecurity in the aftermath of a brutal war.

With local officials warning that more than two million people are now at risk of starvation, the BBC has gained exclusive access to some of the worst affected areas in Tigray province, and analysed satellite imagery to reveal the full scale of the emergency the region now faces.

The month of July is a critical period for food security, when farmers need to plant crops to take advantage of the seasonal rains.

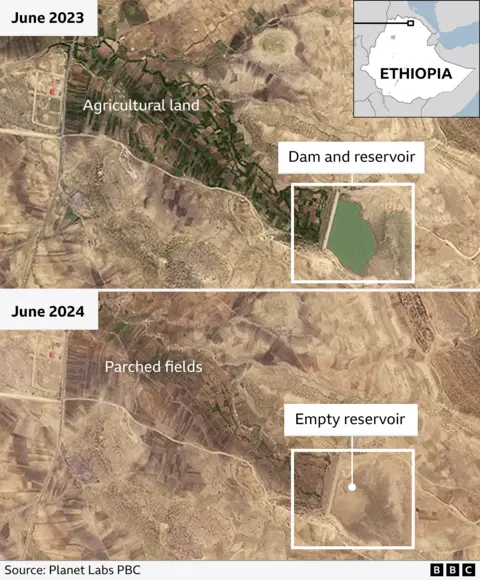

The satellite images we have identified show that reservoirs, and the farmlands they help irrigate, have dried up because the rains failed last year. They now need to be replenished by seasonal rains if farmers are to stand any hope of a successful season later in the year.

The images below are of the Korir dam and reservoir, about 45km (28 miles) north of the regional capital, Mekele.

A small lake with an artificial barrier, known as a micro-dam, is clearly visible in the first photograph, taken in June 2023. Below the dam is fertile land irrigated by the reservoir.

Systems such as this have been able to support more than 300 farmers growing wheat, vegetables and sorghum – a grain crop.

The lower image shows the same area in June 2024, with the reservoir empty and parched fields.

Without adequate rainfall, the irrigation system cannot operate and farmers are unable to survive off the land.

“Even though our dam has no water, our land will not go anywhere,” says Demtsu Gebremedhin who used to farm tomatoes, onions and sorghum.

“So we don’t give up and we hope we will go back to farming.”

Food and security

Tigray’s population is estimated to be between six and seven million.

Until the end of 2022, the region was engulfed in a bitter two-year war pitting local Tigray forces against the federal government and its allies.

It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people were killed in the conflict, or died because of starvation and lack of health care.

Dozens of displacement camps were set up to provide refuge, and humanitarian support.

Ed Ram/Getty

Ed Ram/GettyNow the war is over, some have been able to return home – but most have remained in camps, reliant on food aid being delivered there because the lack of rainfall has meant they have no crops to harvest and eat.

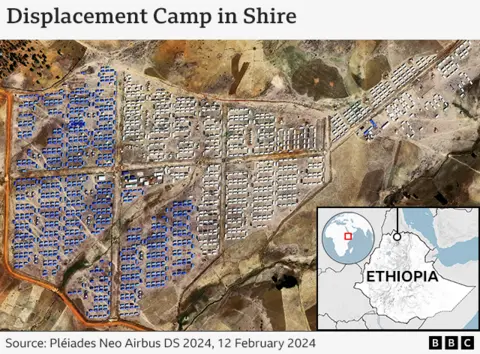

One of these camps is near the town of Shire about 280km (174 miles) by road to the west of the Korir dam. Set up by UN agencies, it now provides shelter to more than 30,000 people.

The blue tents seen in this satellite image have been provided by the International Organization of Migration (IOM) and the white by the UN refugee agency (UNHCR).

Pléiades Neo © Airbus DS 2024

Pléiades Neo © Airbus DS 2024Tsibktey Teklay looks after five of her children in the camp. Her husband was killed in the war.

“We had animals. We used to harvest crops in winter,” she told the BBC in May. “In short, we had the best lifestyle. Now we are down to nothing.”

In the camp, she does some cooking and some handicraft work to earn money, but some of her children have had to beg.

“I hope I will get my land back at least. Food grown on our land is better than food aid,” she says.

“If we can return to our home town, our children can work or go to school.

“So I hope that after our miserable life here, this will be the best future for them.”

Children facing malnutrition

The BBC has spoken to doctors at a hospital in the town of Endabaguna, some 20km (12 miles) south of Shire about their growing concerns.

“We’ve been treating increasing numbers of children in recent months,” says the hospital’s medical director, Dr Gebrekristos Gidey.

One woman – 20-year-old Abeba Yeshalem – gave birth prematurely as a result of malnutrition, he says.

At the hospital, Abeba told us: “My husband went away to study, leaving me on my own, and he was unable to help me financially. I don’t have enough food to feed either myself or the baby.“

The dozens of children being treated are not only from families living in the camps, but also those from the nearby towns.

“We don’t have the resources to care for all those in need,” says Dr Gebrekristos.

Waiting for the rain

The region is facing its most critical time of the year, known as the “peak hunger season” according to Dr Gebrehiwet Gebregzabher, head of the Disaster Risk Management Commission in Tigray.

It is a time when food supplies traditionally run low – and crops must be planted to be ready for the October harvest.

“There are 2.1 million people that are at risk of starvation,” he tells the BBC, “with a further 2.4 million relying on an uncertain aid supply.“

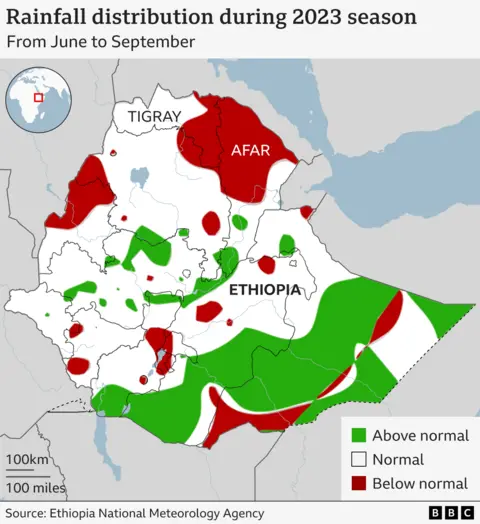

Data obtained from the Ethiopian government’s meteorology agency shows the consequence of poor rains last year.

Tigray’s northern regions and neighbouring Afar both suffered from drought.

To the south of Ethiopia, heavy rains caused flooding, with damage to crops and livestock.

Rainfall in January and February this year was also below normal in large parts of Tigray, although it improved in some areas in March.

Political tensions

Famine “creeps up in the darkness” warns Prof Alex de Waal, executive director of the advocacy group, the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University. He says too little attention is being paid to the crisis.

“Famines are man-made, so the men who make them like to conceal the evidence and hide their role,” he says.

He says the current situation in Tigray has echoes of the catastrophic famine of 1984 in which as many as a million people died of starvation.

“In 1984, the Ethiopian government wanted the world to believe that its revolution heralded a bright new era of prosperity, and foreign donors refused to believe warnings of starvation until they saw pictures of dying children on the BBC news.”

Aid agencies have mapped the scale of the crisis facing Ethiopia based on a range of factors, including failed rains, ongoing insecurity and a lack of access for aid distributions.

The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (Fews Net) describes parts of Tigray, along with neighbouring Afar and Amhara, as facing an emergency

Getty/Ed Ram

Getty/Ed RamThe federal government in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa disputes these warnings of critical food shortages.

Shiferaw Teklemariam, head of Ethiopia’s national Disaster Risk Management Commission, told the BBC that based on official assessments “there are no looming dangers of famine and starvation in Tigray…[or] elsewhere in Ethiopia.”

He added that officials were “doing their best” to address the challenges facing the country and that “beneficiaries most in need” would continue to be prioritised.

Relations between the Ethiopian government and aid agencies have been strained in recent years, amid allegations from the UN that food aid was being blocked from reaching Tigray during the conflict there.

In 2021, the federal government denied reports of hunger in Tigray and expelled seven senior UN workers, accusing them of “meddling in the internal affairs of the country”.

Then in June last year, the UN’s World Food Programme and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) suspended all food aid to Ethiopia, saying they had uncovered evidence that government and military officials were stealing humanitarian supplies.

Deliveries were only resumed in November.

There have also been public disputes within Ethiopia about the severity of the situation.

In February, after Ethiopia’s ombudsman reported nearly 400 deaths from hunger in the country, including in Tigray, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said: “There are no people dying due to hunger in Ethiopia.”

In response to these political tensions, Alex de Waal says aid agencies which are “strapped for cash and averse to controversy” have been slow to respond to the current crisis.

A spokesperson for USAID told the BBC they “continue to urge the government of Ethiopia and other donors to increase funding to the humanitarian needs of the most vulnerable”.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) says the funding currently available is “insufficient to meet the extensive humanitarian needs”, but the resources available are channelled “to the most urgent, life-saving response.”

Additional reporting by Daniele Palumbo and Kumar Malhotra