Britain’s bores didn’t know what to do with Wendy James. As the frontwoman of Transvision Vamp, that Eighties collision of brash punk and commercial pop, she was smart and moody, sexy and confounding, cool and unflappable. Naturally, she had to be destroyed. “Wendy James, John Sessions, Jeremy Beadle and 97 more in our Hated 100,” went the cover of a 1989 issue of Time Out magazine, alongside a photo of James defaced by a smashed pie. Ah, the good old days. What else probably got their backs up? James really, really didn’t give a damn.

“It never occurred to me for a second that I wasn’t equal,” the 58-year-old says today, proudly. She’s wrapped in a pink coat in the living room of her home in the south of France, her blonde hair lacquered to her scalp, her eyes thick with black liner. “I was the f***ing leader,” she continues. “I was the engine. You could put me on a roster with 10 different acts and I’d go out there to win. Most pop stars worth their salt will have that same killer instinct. I was never a victim. If you were offensive, I’d be like Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver. ‘Are you f***ing talking to me?’” Her cut-glass English accent may be delicate, but she reels off that famous line with such quiet force that I feel like running and hiding.

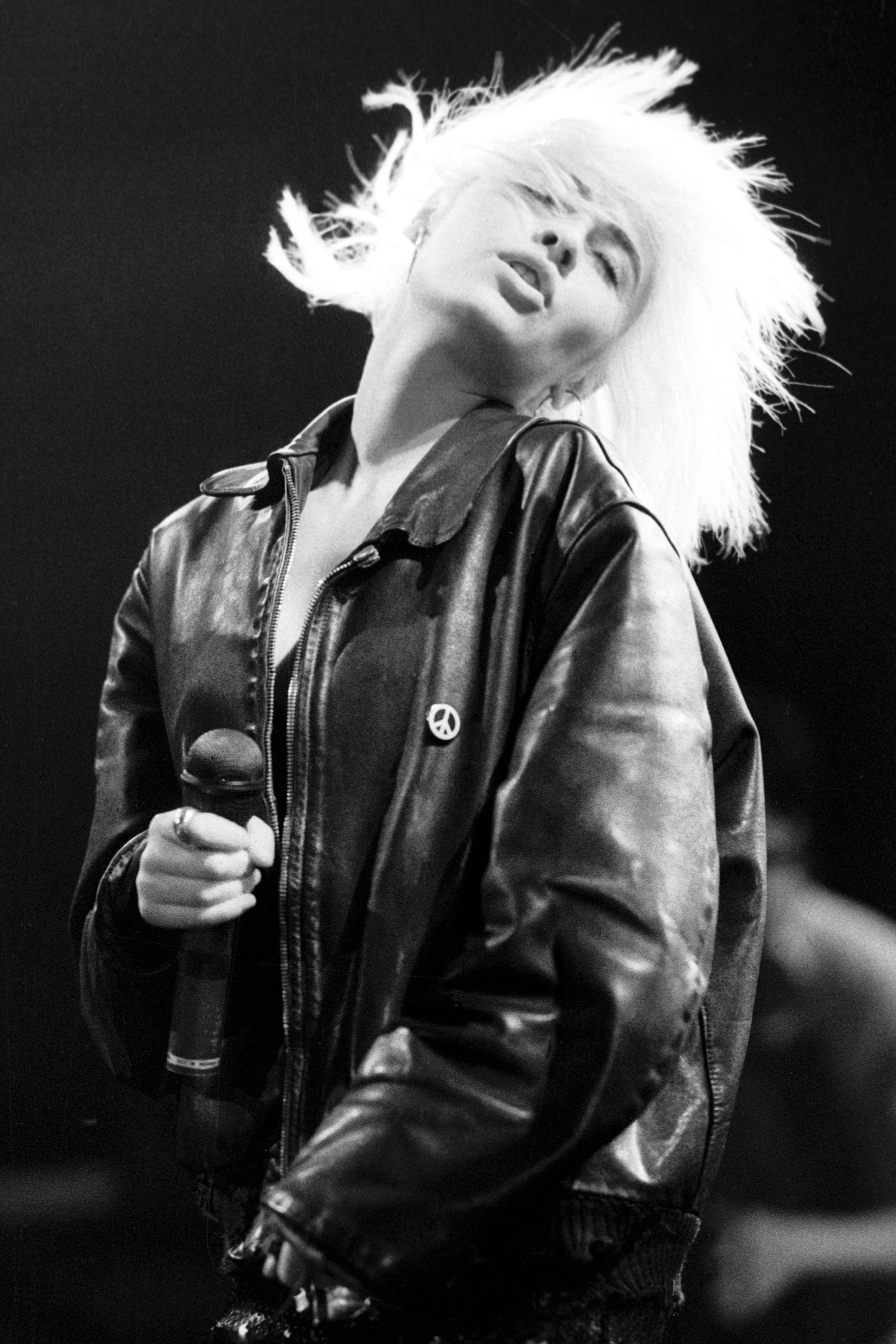

That mix of soft and scary was always at the heart of James’s appeal. With her peroxide bob, powder-pink lipstick and performative snarl, James embodied the persona of the “teenage girl gone wild”. Shortly after meeting between London and James’s hometown of Brighton, she and her bandmates marched into EMI Records insisting they were going to be the biggest band in the world – then immediately got signed. Their most successful singles were similarly full-on, thrumming with sex and violence. Nothing else in British pop at that point sounded quite so anarchically fun, all scuzzy guitars and bratty shrieking.

“I don’t want your car, baby/ I want your ughhhh!” James moaned on 1988’s “I Want Your Love”. “Tell that girl I’m gonna beat her up,” threatened an earlier single, “Tell That Girl to Shut Up”. “You can tell me all your stories/ But please spare me the plays,” she sassed on 1989’s “Baby I Don’t Care”. Listen to their deeper cuts, though, and James could be mournful and self-aware. “Oh I’m so bad, bad, bad, all the time,” she sulks on the regretful “Bad Valentine”. “You got the skies and you got the stars/ And you got the power to break a young heart,” goes the elegant dream-pop of “Sister Moon”.

“Some people have an instinct to gravitate towards destruction, but I am the opposite,” James says. “Were there cracks? Yes, I’m sure – you do have moments where you’re on the bed crying and thinking you’re all alone. But that’s all it was. You get up the next morning and you go again.” She knows, though, that she’s had it lucky. Her new album The Shape of History – her seventh since the breakup of Transvision Vamp – is pop and blues and thrash rock, its lyrics underpinned by a kind of wisdom that can only come from years of hustle and adventure.

“I was a tough little f***ing teenager,” she says. “I had armour. I had a force field. But not everyone comes equipped with that – you just see the f***ing battering that people in their twenties and thirties take. So some of the record is me going, ‘I’m here for you – it’s all gonna be OK.’”

Being flirty or sexual? That’s just who we were. And whether you’re famous or not, young girls f***ing show out, don’t they?

The album sounds like a patchwork of memories – victories, heartaches, the feeling of racing down a California highway, no destination in mind. Today, James guides me along a roadmap of the record’s influences. Joan Didion. Hunter S Thompson. The Fall. Dancing on tabletops. Love affairs and screwball comedies. Breaking America. She remembers being stranded on the freeway, and a truck stopping and driving the band to the auto shop. “I was wearing this minidress with green sequins,” she adds, grinning wistfully.

Throughout our conversation, she zigzags through contradicting emotions. At one point, while discussing the invasion of Ukraine, she begins to cry; at another, she becomes exercised, shouting furiously about misogyny, power structures and the murder of Sarah Everard. “Women do get taken more seriously now,” she says, “but not if you get raped by a f***ing copper.” James is passionate, opinionated, righteously angry.

For journalists in the past, being faced with quite so many Wendy James dimensions at once seemed to spark confusion. “Exploiter or exploited? Rock bitch or just bitched at?” asked Vox magazine in 1991. “Either way, she loves the attention.” Asked about this today, she says she really was just a bundle of things back then.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

“I surrounded myself with punks and boys from other bands, so I grew up with that tough, boy-gang mentality,” she says. “I wanted to walk into town and throw down. And being flirty or sexual? That was just the kind of teenager I was. I was f***ing happy! And, honestly, the girls who were my friends at the time – Bananarama, or any of us – we were all running around town in little bra tops and dancing our tails away at the Café de Paris. That’s just who we were. And whether you’re famous or not, young girls f***ing show out, don’t they?”

Why did people seem so bothered by you, though? “Women have to prove themselves twice as much as men,” she sighs. “And whether it’s rape victims or pop stars, women are expected to explain themselves, when it should be the perpetrator explaining it.” She thinks things are better now – but only just. “‘Atavistic’ is the word Hunter Thompson would use,” she says. “‘Man equals hunter, woman equals mother’ – we get thrown back into these ridiculous cliches, and that’s not even touching on gay and transgender rights. There are too many variables in the human species to make everyone who isn’t a heterosexual man subjugate to a particular power structure.”

We talk about tabloid parlance. “‘She’s got a nice set of pins,’” she recites, before mock-gagging. “‘Look at her hot body on the beach’ – but then you see Elon Musk with his blubber fat hanging out over his boxer shorts, and it’s disgusting.” She hoots with laughter. “So, yes, we’re making intellectual and factual improvements, but when the old basic instinct kicks in? We get pulled back into the cave.”

James has lived between France and New York since the early Noughties. Britain in the Nineties, in the wake of Transvision Vamp disbanding in 1992, was a bit of a creative wasteland for her. Her unusual first solo record, 1993’s Now Ain’t the Time for Your Tears, was entirely written by a man she’d only briefly met: Elvis Costello, his lyrics inspired by what he thought he knew about James via the tabloids. She then parted ways with her label and, upon the end of a long-term relationship, decided to decamp to New York in 2002.

“New York meant freedom,” she explains. She threw out her belongings and all the detritus from her Transvision Vamp days, and bought a one-way plane ticket with just a suitcase in hand. Inside it was a skirt, some jumpers, a copy of Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home and a collection of Tom Wolfe essays. For a month she crashed on the sofa of her former bandmate Tex Axile, then, dipping into the pot of money accumulated from her pop star days, bought an apartment in the city’s East Village. The solo work that followed tended to be loose and experimental – full of attention-demanding choruses and sonic detours inspired by everything from T Rex to The Shangri-Las to The Stooges.

“Other journalists have asked me what it’s like to be famous and then not be famous, because I did everything arse backwards,” she laughs. “I took ownership of ‘Wendy James’, started over, learnt to write songs and play guitar. Usually you learn to write songs and start out in the bedsit and move on up – but we exploded big, and only after did I go back to the little studio and make my little demos. It was just work, work, work.”

Before we part ways, I ask James about an appearance she made on Michael Aspel’s talk show in 1991, where she told the presenter that she felt as if she’d “created” herself from scratch. She still thinks it’s accurate – she was adopted at birth, and has chosen to not try to find her birth parents. “And what that means is that you start off with a blank slate,” she explains. “I can’t trace my medical history. There was no question of going into the same work field as my birth parents, because I didn’t know what they did. So in that respect, I created myself – I was unburdened by the past, because there was no past. I haven’t had children either, so when it ends, it ends with me. I’m just this little micro-blip of its own thing.”

She laughs, thinking about her legacy.

“And I suppose what I’ll leave behind is the people I’ve been nice to, the experiences people have had as they’ve passed through my life… and the music.”

‘The Shape of History’ is released on 25 October