In recent weeks, Ukraine’s hopes have been buoyed that its Western allies will finally allow their long-range weapons to strike deep into Russian territory.

Since the beginning of the full-scale war, Russia has been able to attack Ukraine with relative impunity from its positions behind the border, while the U.S. and other suppliers of weapons have forbidden Ukraine from using their supplied weapons to strike back, often citing fears of escalation.

There were signs that the tide was shifting over the past week. The Guardian reported that the U.K. had already decided to allow Ukraine to use its Storm Shadow missiles for strikes in Russia. Politico wrote that the White House reportedly is discussing potential targets Ukraine could strike with its long-range weapons.

But hopes of a positive announcement during meetings between President Joe Biden and U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer in Washington on Sept. 13 were dashed, and the decision-making process appears to have been postponed to the UN general assembly in New York later this month.

A day later on Sept. 13 in Kyiv, U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said allowing Ukraine to use ATACMS to strike targets deep inside Russia is the subject of “intense consultations.”

Ukraine has been eagerly awaiting the potential lifting of restrictions, with Defense Minister Rustem Umerov saying in August that he had presented the U.S. with a list of proposed targets within Russia.

Calling the lifting of restrictions a “game changer is probably too strong a word,” Andreas Umland, analyst at the Stockholm Center for Eastern European Studies, told the Kyiv Independent.

“But it would make a big difference of course. That’s why the Ukrainians are so eager to get it.”

Potential targets

A public list of targets — either those requested by Ukraine or approved by the U.S. or the U.K. — is unlikely for operational reasons.

Western officials have been hesitant to openly talk about policy changes, likely out of concern that Russia will relocate potentially valuable targets out of reach before Ukraine is able to capitalize on its newfound range capabilities.

But matching the ranges of the weapons available to Ukraine, to Russian positions on the other side of the border can shed light on what might be possible should the policy be officially changed.

A report from the Institute for the Study of War last month identified “no fewer than 245 known Russian military and paramilitary sites” within the 300-kilometer range of U.S.-supplied ATACMS, which is currently the furthest range of any Western-supplied missiles available to Ukraine.

If placed close to Ukraine’s front lines, the Western-supplied long-range weapons could potentially put vast swathes of Russian territory in the firing zone. The area includes military bases, airfields, troop concentrations, and ammunition depots.

Numerous population centers would also be in range, including the cities of Rostov-on-Don (population 1.1 million), Voronezh (population 1 million), Krasnodar (population 1.1 million), Lipetsk (population 496,000), Bryansk (population 350,000), Smolensk (population 310,000), as well as the key port city of Novorossiysk on the Black Sea (population 262,000).

This non-exhaustive list does not include cities in occupied Crimea or other parts of Ukraine under Russian control or cities in Russia that have already reportedly come under Ukrainian attack, such as Belgorod.

Any change in policies is likely to come with strings attached and with the understanding that long-range strikes will be conducted in a defensive fashion on military targets.

Some of the possible military targets in this area could include the following:

- Lipetsk military air base, struck by drones in August

- Shatalovo air base in Smolensk Oblast

- Millerovo military airfield in Rostov Oblast, damaged in a drone strike in July

- Yeysk military airfield in Krasnodar Krai, damaged in drone strikes in June and April

- Logistics and command centers in Rostov-on-Don, which has been the central headquarters of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine

- The Primorsko-Akhtarsk airbase in Krasnodar Krai, regularly used by Russia to launch Shahed-type drones at Ukraine

- Novorossiysk naval base, where much of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet has relocated after a series of devastating attacks by Ukraine on its primary base off of occupied Crimea

Missiles — range and uses

Ukraine’s Western allies have supplied several variants of long-range missiles after initial hesitation at the beginning of the full-scale war — albeit with the caveat that they are used for strikes within Ukraine or in Russian-occupied parts of the country.

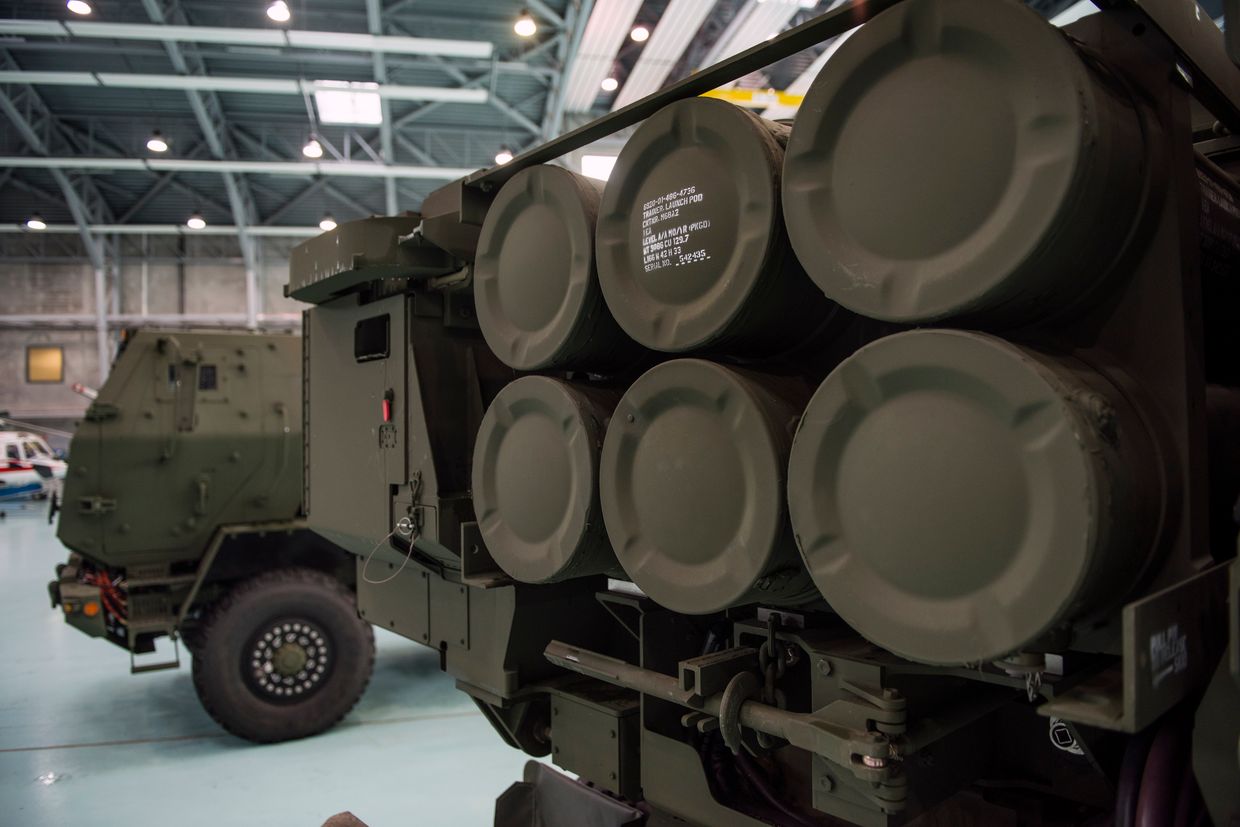

HIMARS, whose prowess became a popular motif of internet memes, was a game-changer for Ukraine when they first arrived in the summer of 2022.

Initially supplied with GMLRS rockets with a range of around 70 kilometers, they allowed Ukraine to target Russian forces on the other side of the front line far more accurately than they had previously.

In the fall of 2023, the U.S. began supplying Kyiv with an older model of ATACMS – fired from HIMARS launchers – with a range of around 165 kilometers, greatly increasing the range that Ukraine could strike within.

Ukrainian drones strike deeper into Russia, aiming to break war machine, sow discontent

Just before sunrise on an otherwise sleepy weekend near Moscow, a Russian eyewitness of Ukraine’s kamikaze drone attack on the Kashira Power Plant appeared stunned, unleashing an expletive-laden tirade with his wife alongside. “They f***g attacked the power plant! Wow, honey!” he said in a video po…

The tide began to shift after Russia’s renewed offensive in Kharkiv Oblast in May, when the U.S. and other Western allies eased restrictions, allowing Ukraine to strike targets with Western weapons— in a defensive fashion — inside Russia.

As the West dithered on its policy about long-range strikes, Ukraine has developed its own domestic arsenal of drones to attack targets inside Russia, hitting airbases, ammunition dumps, drone factories, and other military sites as far as 1,300 kilometers (800 miles) beyond the Ukrainian border.

The U.S. began supplying Ukraine with an older model of the Army Tactical Missile Systems (ATACMS) in the fall of 2023, which have a range of around 165 kilometers. In the spring of 2024, the New York Times reported that the U.S. had shipped around 100 updated versions of ATACMS missiles, which can reach up to 300 kilometers.

Ukraine has put both variants of missiles into effect on the battlefield, striking targets in occupied Crimea and other parts of Ukraine occupied by Russia.

The U.K. began providing Ukraine with its long-range Storm Shadow missiles in May 2023. The missiles have a range of over 250 kilometers. The missiles have been deployed in a number of devastating attacks on Russian targets, such as a strike on the Black Sea Fleet headquarters in occupied Crimea that reportedly killed dozens of Russian soldiers and officers.

Although its official list of targets has not been revealed, Ukraine has repeatedly stated that it needs the ability to strike the Russian aircraft that launch mass missile attacks against Ukrainian cities, and the airfields from which they take off.

“The Storm Shadow is best used against heavily protected buildings like bunkers or reinforced ammunition storage sites and headquarters,” Matthew Savill, director of military sciences at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), told the Kyiv Independent, adding: “It isn’t the best use of it to try and hit aircraft out on a runway, or against an airfield that is easy to repair.”

“There are such targets available in Russia, but they’ll need to be carefully picked to maximize the impact, ideally timed to coincide with Ukrainian ground operations, destroying supplies that Russian ground units need.”

Savill said that the cluster weapon version of ATACMS is ideally suited to striking Russian aircraft at Russian airfields, but added that a recent report that Moscow has already transferred around 90% of its military aircraft to bases outside their reach suggests their effect may now be limited.

“This at least means (Russian aircraft) have to operate from further away, and can fly fewer sorties per day,” he said.

“There will be Russian forces still in ATACMS range, but essentially it sounds as if the opportunity to do serious damage to the Russian air force on the ground has been missed, for now.”

Despite potential missed opportunities, the lifting of restrictions will still be welcomed in Ukraine.

“It will certainly make a lot of difference in the war, and will help protect Ukrainian cities from these ongoing missile terror attacks,” Umland said.

Russian cities left defenseless as Ukraine ramps up drone attacks

While waiting for a green light from Western countries to use their long-range weapons to strike targets deep inside Russia, Ukraine is relying on domestically produced drones, which are considerably cheaper than missiles and no less effective. In recent months, Ukraine has increased the number of…