BBC

BBCThe last remaining blast furnace in Port Talbot will stop producing steel on Monday, ending the traditional method of steelmaking in south Wales.

Tata Steel is expected to remove the last usable liquid iron from blast furnace 4 on Monday afternoon.

The closure of the heavy end at the UK’s largest steelworks is part of a restructure that will cut 2,800 jobs.

Future steelmaking in Port Talbot will rely on imports until an electric furnace, which melts scrap steel, is built.

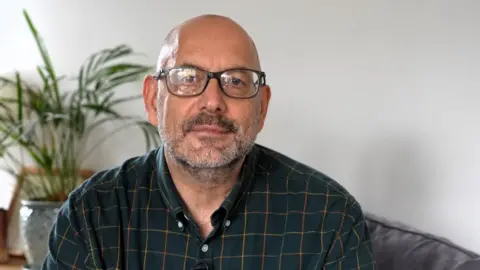

Owen Midwinter, who’s from Port Talbot, has already finished his last shift in the blast furnace control room.

He wants to stay with Tata, but said he is “in limbo” while he finds out if he will be matched to a job in another part of the company.

“Every day there are rumours, it plays on your mind a bit,” he said.

Owen said he accepts he may have to move away to find the kind of work he wants.

“If the worst comes to the worst and I do get made redundant, I’d want to stay around here,” he added.

“I’ve got my family, I’ve got the football club. But that might not be a possibility.”

He said there are mixed emotions amongst employees. For some, the significance “has hit home a bit”.

“They’re feeling it now, they’ve been there for years and years, and now it’s finally coming to an end.”

But a lot of people are “just getting on with it”, he said.

“It’s been a long process now and they’re counting down the days for it to be off and they can start a new beginning elsewhere, either in the company or on their own.”

Blast furnaces produce molten iron by splitting rocks containing iron ore. It is a chemical reaction that requires intense heat, and which emits high levels of carbon into the atmosphere.

It is known as primary steelmaking, or virgin steelmaking, as it extracts iron from its original source and can be purified and treated to make all types of steel.

The BBC was given permission to record inside the blast furnace during its final days of operation.

James Raleigh, who has been involved in operating both blast furnaces in Port Talbot, said: “I have been in there quite a few times, but it is still very impressive to me.”

The works technical manager for the coke, sinter and iron department added: “Working in this industry, the scale of it is absolutely huge. It is still very impressive every time I go in there.”

Temperatures inside the furnace reach over 2,000C (3,632F) with liquid iron “tapped” by workers flowing out at a temperature of around 1,500C (2,732F).

The first of Port Talbot’s two blast furnaces was taken out of service in July, while the closure of the second will mark the end of primary steelmaking in Wales.

Tata Steel UK has consistently said that its blast furnace operations were losing £1m a day, and it will invest £1.25bn in an electric arc furnace which would reduce emissions and secure the future of steelmaking.

The UK government has committed £500m towards the cost of the new technology, with construction set to begin in August 2025.

In the meantime imported steel slab will be milled in Port Talbot to continue supplying customers and Tata’s downstream sites in Trostre, Llanwern and Shotton.

Prof Geraint Williams from Swansea University said the end of blast furnace production was “a turning-point in steelmaking” in the UK.

“You are removing the capacity of the UK to be able to produce its own primary steel,” he said.

“What is produced in an electric arc furnace isn’t primary steel. What you’re doing is recycling steel. You’re re-melting it.”

Prof Williams said the closure of Port Talbot’s furnaces, and the expected closure of the UK’s last remaining blast furnaces in Scunthorpe, signalled a major change in the country’s industrial history.

“Great Britain is the birthplace of the industrial revolution, so it’s very surprising that – eventually – we will lose the ability to produce steel from scratch.”