Some 150,000 Wembley-goers can’t be wrong: Bruce Springsteen is worth every penny of his newly minted status as A Billion Dollar Rock Star. This past week the 74-year-old boss of all bosses played twice at the stadium, earthquaking event concerts that The Independent’s reviewer characterised as a “three-hour shift of blazing, hi-octane rock’n’roll [with] no sign of the wear and tear dogging other such Sixties and Seventies greats”.

That cash valuation came from the blue-chip bean-counters at Forbes, their calculations arising in large part from Springsteen selling his song catalogue to Sony in 2021 for a reported half-a-billion. Then there were the 1.6 million gig tickets he sold last year, bringing in another $380m.

How meaningful, one wonders, is that $1bn status to a superstar who’s sold 141 million albums and won 20 Grammys, an Oscar and a Tony in a 50-year-plus recording career? His best pal probably has the answer.

“It’s great for me because I’m gonna definitely borrow some money, I tell you that. I’m joking, of course,” says “Little Steven” Van Zandt, the guitarist who’s been standing stage-left of Springsteen, on and off, since their shared teenage garage-band origins in New Jersey. “My bookie’s gonna love him. I’m joking again!

“I’m not sure how accurate that is, first of all. But I don’t think it matters, honestly,” continues this time-served stalwart of the outfit Springsteen introduces from the stage as “the heart-stopping, pants-dropping, hard-rocking, booty-shaking, love-making, earth-quaking, Viagra-taking, death-defying, legendary E Street Band”.

Van Zandt is Zooming in from his suite at Claridge’s: “When you have enough money to live, that’s the point where it matters. Do you continue to work? Or do you retire on a yacht and drink mojitos off the coast of Portugal? The fact is: this is what we do. And so the money has absolutely no factor. It hasn’t affected [him] for many, many years. Ever since, really, [1984 album] Born in the USA. What’s that, 40 years?

“So no matter how many zeros is on the bank account, it doesn’t make any difference!” this piratical charisma-bomb cracks again, his pearly white super-smile almost as loud as his ever-present bandana and scarves.

Even at 11am on a Saturday, a weekend morning wedged between two stadium gigs and a special screening the previous evening of Van Zandt’s new HBO bio-doc Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple, the 73-year-old gives good rock’n’roll showmanship. It’s a skill that’s served him well across music, political campaigning and an iconic TV acting role as right-hand man to another kind of boss in The Sopranos.

Disciple director Bill Teck justifies making a film that lasts almost as long as a Springsteen show as “Stevie was involved in so many different things, people may not know the whole journey. They may not know that Silvio Dante helped free Nelson Mandela.”

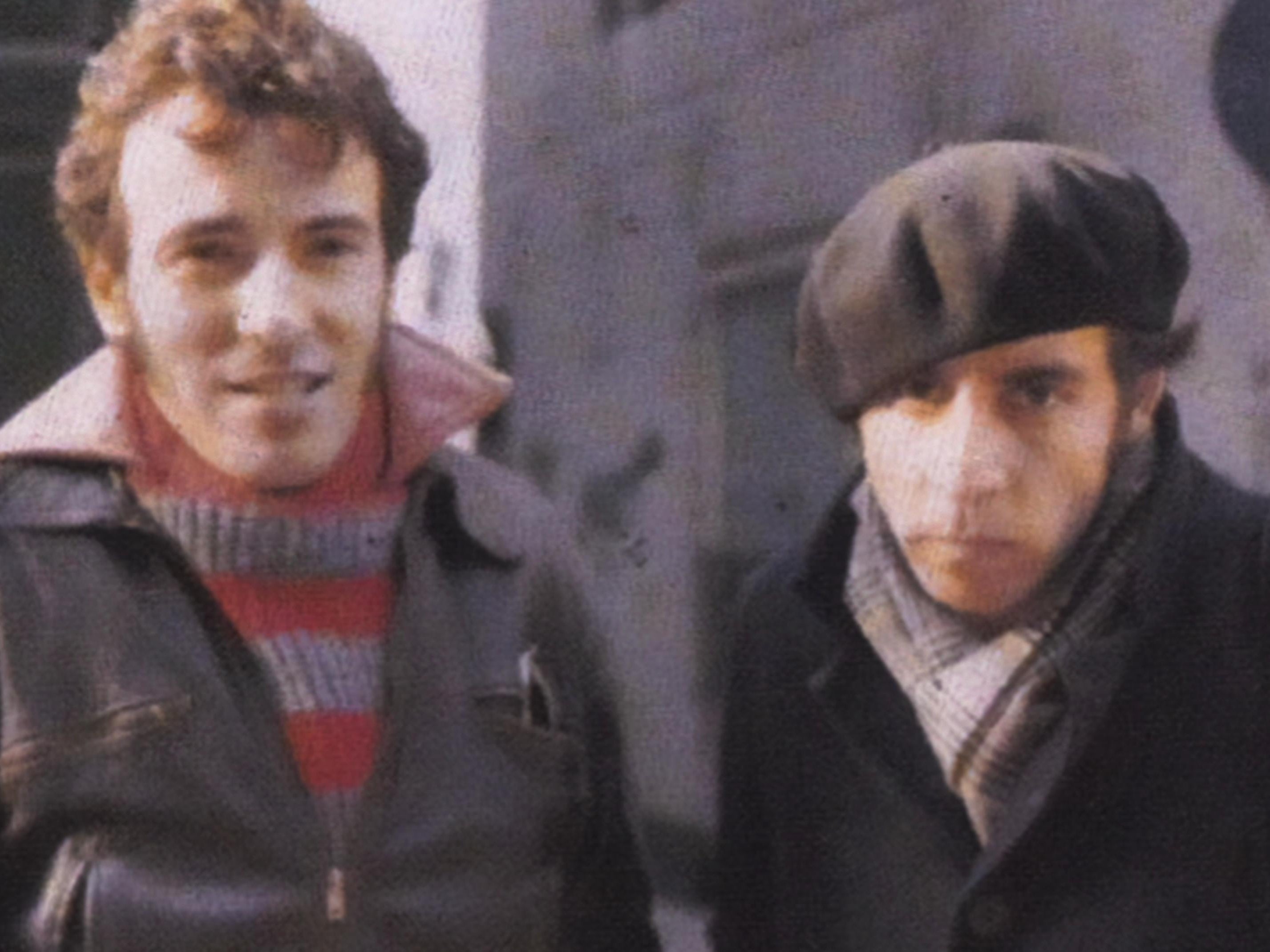

That skill has been honed with Springsteen since their days in The Source and The Castiles, respectively, rival mid-teenage bands on the Jersey shore. In Disciple, Springsteen recalls how Van Zandt “became my rock’n’roll brother instantly”. Then, once The Boss leapt ahead of his peers and landed a recording contract, Van Zandt became his “sounding board… I wanted him near me, I wanted him by my side.”

But Van Zandt forged his own path, too. With his own band, The Disciples of Soul. With his forming of Artists Against Apartheid, the 1980s organisation with which he rallied rock’s conscience to the cause of freeing Nelson Mandela. And with his knack for songwriting, production and arranging, for projects and artists including 1985 AAA protest anthem “Sun City”, Springsteen, Gary US Bonds, Darlene Love and the soundtrack to Home Alone 2: Lost In New York.

Helping Teck deliver that story are talking heads ranging from Bono to Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, Paul McCartney to Peter Gabriel, Sopranos’ creator David Chase to Van Zandt’s wife Maureen (who also played Silvio Dante’s screen wife), and, of course, Springsteen.

“It was very bonding back then, even though we were 15 – being in rock’n’roll was still an unusual thing to do,” says Van Zandt by way of explaining the pair’s lifelong connection. “It was a very small cult. A tribe of misfits, outcasts and freaks that really did not fit into society… But me and him really took it seriously right from the beginning, knowing that this was a lifeline that we very much needed in our own ways.

“Beyond that, we both had a really strong work ethic, and a compassionate, independent, liberal philosophy in terms of feeling like we’re on the planet to help a little bit. Make things a bit better for the next guy. As opposed to every man for himself, let’s make as much money as we can, and don’t worry about the rest of the world. We shared a morality and compassion that I think helps keep the friendship more solid.”

That was tested, but also proven, when, in 1983, Van Zandt decided to leave Springsteen’s side after 15 years – just before the release of the record that would change the life of the latter and, arguably, the course of Eighties rock. Reflecting now, Van Zandt acknowledges that he wasn’t thinking of “the big picture” when he quit ahead of Born in the USA, lest he become what he calls an “encumbrance” to his friend.

Van Zandt had been around since Born to Run (1975), through Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978), The River (1980) and Nebraska (1982), before the album that caused everything in Springsteen’s life to “go berserk,” he says. “We thought three million records was the most you could possibly sell! And the next one sells 20 million? You can’t blame him for lifting off the ground there for a minute. When those things happen, you don’t necessarily want the guys from the old neighbourhood hanging around! Reminding you that you were once nobody. Even though I think every celebrity and superstar does need that guy from the neighbourhood, reminding them that they were once nobody!

“That’s part of what happened there: not intentionally, not consciously, but he started to distance himself from me,” Van Zandt continues. “And I felt I needed to leave the band in order to preserve the friendship.”

That’s exactly what happened. The pair reconciled soon after, with Springsteen seeking Van Zandt’s advice on “what to do on the Born in the USA tour. That was the meeting where I told him he should start doing benefits at every single show in every single city, instead of the usual things that people did in those days, which was once a year making some kind of charity thing. I said: ‘You got a reputation as a man of the people. It’s time to prove it. It’s time to be it.’”

Equally, Van Zandt’s own conscience was propelling him in another direction. As the architect of Artists Against Apartheid, Van Zandt agreed to be smuggled into South Africa under blankets, which terrified Maureen. Teck describes her response: “I married this rock’n’roll guy – now he’s a political animal? This machine who’s on this mission?” Teck understood her point, “because it was scary and stressful. It did put his entire career and their relationship at risk, Stevie following his passions.”

Certain people literally have a physical aura, you can feel it

Van Zandt, though, got to meet Mandela in person – “I felt what must have been the feeling when people met the great spiritual leaders of the world – if they even existed! – the Moses and Jesus and Muhammad and Buddhas of the world. Certain people literally have a physical aura, you can feel it.”

Having jeopardised his career once, Van Zandt risked doing it again when he took the role in The Sopranos. David Chase had been mesmerised by Van Zandt’s hilarious, role-playing speech when he inducted New Jersey soul band The Rascals into the 1997 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He duly created for the musician the part of pompadoured strip-club owner Silvio Dante in the drama he was developing about a New Jersey mob boss (James Gandolfini’s Tony Soprano) who was in therapy.

But: what if the first-time actor fell flat on his bandana’d face?

“I was concerned about the whole concept,” admits Van Zandt. “This first script is great. What if the second one sucks? As musicians, we’re used to controlling our own destinies, artistically anyway. You sing a song, you come into the [studio] control room, you say, ‘I think I could do a better job’, and you go and try it again.

“This thing: you act in a scene. The director – who’s never seen you before in his life – decides whether you just did the right job or not. And you’re gonna see it six months later. What a freaky sort of way to make a living! My life’s gonna depend on some total stranger?”

How were his connections with the show’s proper actors?

“That was the other thing I was very concerned with. Are these guys gonna accept me, half a hippie guitar player coming off the street? But It turns out Jimmy [Gandolfini] was completely respectful of what I had accomplished in my other life.”

Even more concerning was Tony Sirico, who played Paulie Walnuts. “He was the real thing – he did time and he was a tough guy,” says Van Zandt. “But we became best friends. Turns out he actually knew my wife from the early days. He used to go into [legendary New York club] The Scene when Maureen was there, seeing Jimi Hendrix. She was there when Tony Sirico was basically pulling up Jimi Hendrix in the bathroom. extorting him for money!”

Then, as the series and roles developed, Van Zandt and Dante found their feet: the newbie actor was playing a character who was consigliere to a boss.

“Jimmy and I bonded on the fact that we’re both character actors – in rock’n’roll language, that’s a sideman. Jimmy was surprised to suddenly find himself a lead actor. And was uncomfortable with it for quite a long time. I mean, he literally quit every other day. Then the writers picked up on the fact that we were bonding.

“Then by the end of the first season, that’s what it became: I became the younger boss and consigliere. And at that point, the entire relationship with Bruce my whole life kicked in. I was like: ‘Oh, I know what the job is now.’ It turned out to be perfect.”

Speaking of The Boss, Steven Van Zandt has to split. It’s almost, again, time to get on stage. He’s conscious of their role in spreading the gospel of rock’n’roll – “the best possible communication that we’ve ever created on this planet” – but he knows too that in live terms, things “can never go back to the Sixties, and Seventies and Eighties. Because the infrastructure is not there.

“The nature of the corporate takeover has changed things,” he continues. “Nobody wants to spend time developing anything any more. That’s the problem with our entire society, our entire culture, not just entertainment. Once the accountants take over the world, which they have, suddenly there’s no concept of development any more. Everybody just wants to deal with the next fiscal quarter. If you’re dealing with the next fiscal quarter, you’re never going to build anything.”

Van Zandt and Springsteen might be millionaires and billionaires, but for these septuagenarian besties, the show must always – will always – go on.

“Bruce hasn’t had trouble paying the rent now for quite a while,” says Van Zandt with another toothy cackle. “That’s the turning point in your life. When you don’t have to do this [for money] any more, do you still do it? But you look at our two biggest heroes and it’s fascinating – The Beatles and The Stones were the biggest when Bruce and I grew up. And The Beatles and The Stones are still the biggest right now, pretty much. Except,” that grin again, “for us.”

‘Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple’ is on Sky/NOW TV