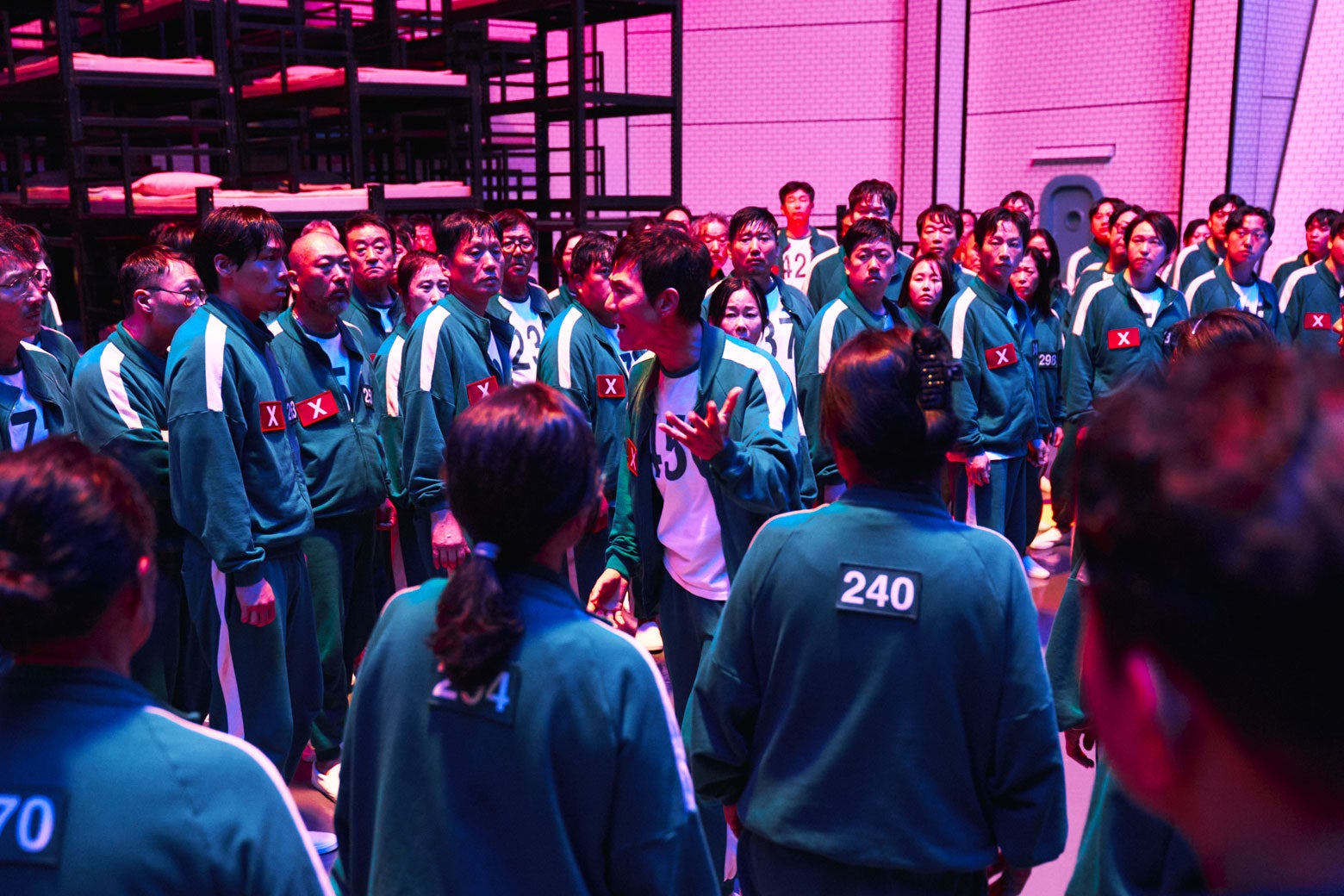

The premise of Squid Game is simple and disturbing. Across modern-day South Korea, debtors are invited to compete in a series of children’s games for a shot at winning a lottery-size cash prize. But lose a game—such as Red Light, Green Light—and you’re eliminated from the running with a bullet to the head or heart. Other ways to go: falling from a great height in a game of tug-of-war, falling from a great height in a game of hopscotch, or falling beneath the blade of a steak knife wielded by a fellow contestant.

In the first season of the Netflix smash, which debuted in 2021, the showrunners unveiled an even more grim facet to the competition midway through the games: It’s a show within a show. The 456 contestants are competing in a battle royal not only to win 45.6 billion won (nearly $31 million) but also to entertain a crew of ultrawealthy sadists who have traveled to the hidden island where the games take place in order to indulge in drink, sex, and gambling. The debtors, all but forced to compete because of their life circumstances, are bet on like horses.

But in the second season of Squid Game, which Netflix released Friday, after a three-year gap in both real life and the show’s plot, the rich VIPs are nowhere to be found. It’s a disappointing absence. The season revisits the cruelties of debt and addiction and introduces new forms of scammery, including a cryptocurrency rug pull that leads a promoter and his victims into a new round of the games. Arguably the most important characters in the game—those who drive demand for the titular horrors by watching and, presumably, funding them—go unexplored.

Squid Game is a drama with an absurd plot. But the games themselves echo the dynamics of something vastly familiar to us: reality television. In these real-world games, contestants also vie for prize pots of literal cash—or else the attention that can be parlayed into a career as an influencer or to generally sell stuff. In some cases, part of the reward is a lavish TV wedding, including a check for your services as “talent.” In exchange, contestants on these shows are often pushed into extreme situations that, while not life-threatening, can be psychologically terrible. Colton Underwood famously jumped over a tall fence to escape The Bachelor during his season as the romantic lead after his favorite suitor left the show. (Things got even dicier after the cameras stopped rolling.) On The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, cast member Lisa Barlow broke down during a hot-mic moment in which she lashed out at and alleged that her friend and fellow cast member Meredith Marks had “slept with half of New York.” On CBS’s The Summit, in which a group of contestants trek through the mountains, one player was made to sever a rope bridge with an axe while another contestant, 52-year-old Bo Martin, was crossing it. Though Martin was wearing a safety harness, the audience was still treated to slow-motion shots of him falling and in apparent shock.

On Squid Game, the masked VIPs who watch contestants fight to the death force the adept viewer to confront the cruelty of their own participation in their favorite hate-watches. Our shows also involve real human beings who are messed with for our entertainment. Yes, our voyeurism is twisted to a far lesser degree, and people on those shows know, to an extent, what they’re signing up for. But when we watch reality TV, we fundamentally tune in to see humans pushed into unnatural forms and to watch them endure humiliations and even a little cruelty.

Yes, reality TV is still delicious to watch, even in its moral grayness. We’re human. Why shouldn’t we want to fill our minds with paragons of human foibles? Why shouldn’t we crave comedy and tragedy from D-tier Instagram influencers and Hermès-clad housewives? Do we watch to enjoy their downfall—which is, after all, merely humiliation, not death—or to see strange facets of humanity reflected back at us, to think about how we’d act in those extreme situations, and to even genuinely root for them to find love and success?

I think it’s kind of both, and we shouldn’t let ourselves off the hook for contemplating the unsavory side of it. Through the VIPs in Squid Game, we’re forced to confront our role in the demand side of this economy and that our viewing in and of itself is complicity with whatever on-screen makes us cringe, pity, or resent. Their absence makes this season less rich.

Luckily, those VIPs will be back for Season 3, set to release in 2025, according to creator Hwang Dong-hyuk. “They’re on the way,” he told USA Today. “Their chopper is flying over the island now.” When they touch down on this isle of nightmares, we’ll all be watching together.