In 2019, Steve Dymond appeared on The Jeremy Kyle Show, taking a lie detector test to prove to his ex-fiancee Jane Callaghan that he had not cheated on her. A week later, the 63-year-old was found dead at his Portsmouth home.

Following the full inquest into his death, which was attended by 59-year-old Jeremy Kyle earlier this week, Hampshire coroner Jason Pegg has now ruled there was “no causal link” between the show and Dymond’s death.

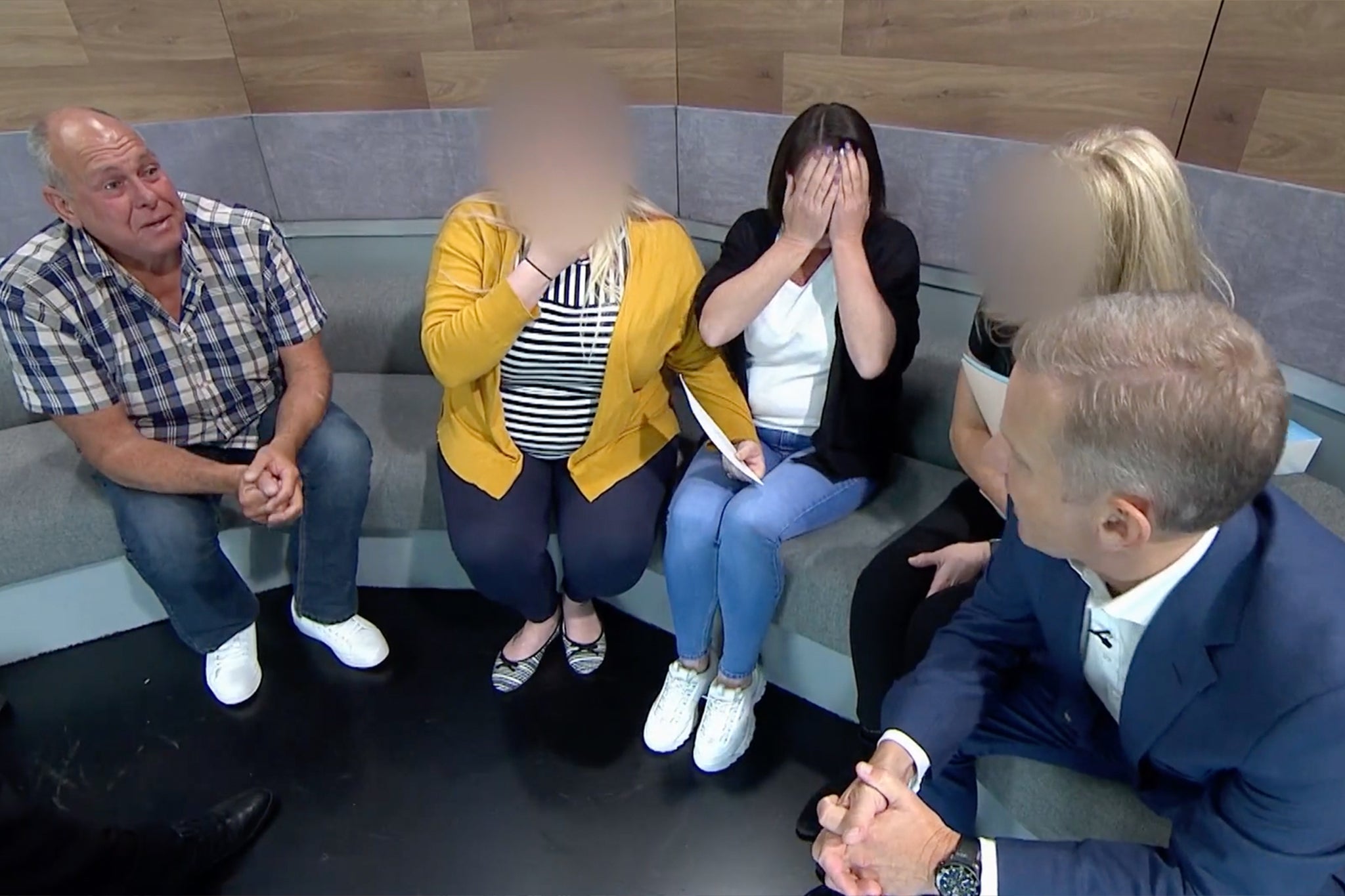

Nevertheless, it’s hard to shake the feeling that the combative format of the show – in which members of the public were encouraged to air their grievances in front of a live (and very vocal) studio audience – is back under a spotlight in a way it hasn’t been since it was cancelled abruptly in 2019.

It was often a jarring and difficult watch. Since it began in 2005, there had been regular calls for the show to be axed, amid concerns about guests’ welfare and how certain situations were handled.

There’s no denying that the show was engineered to be poverty porn – to take the p*** out of the less educated and less fortunate. It wasn’t about resolving family feuds or helping struggling couples through their issues – it was about exploiting them at their most vulnerable, all in the name of “good TV”.

During a Channel 4 documentary, Jeremy Kyle Show: Death on Daytime, former staff claimed they were encouraged to bait the guests and agitate them before they went on, in order to ensure the presenter could get a rise out of them.

While Kyle has staunchly denied these “false and damaging allegations” made against him, viewers witnessed elements of this behaviour on the show; guests were made to endure a dramatic corridor walk onto the set, before settling into armchairs arranged strategically to promote face-to-face confrontation. Lie detectors and DNA tests were used to “prove” who was telling the truth, and waiting in the wings was an ever-present bouncer, in case it all kicked off (no doubt the object of the exercise).

More degrading still was the language used by the host towards his predominantly working-class and underprivileged guests, which was often echoed by viewers at home, and delivered in a provocative manner. Kyle once infamously asked a man whether he knew how to spell the word “father”, mocking his perceived lack of education. On two separate occasions, Kyle told people to “get a job” and “put something on the end of it”. And then there was the time he was recorded calling guests “thick as s**t” in unbroadcast footage.

As a child living in a deprived area (which, coincidentally, is where Dymond’s fiancee is from), who occasionally tuned in to the show (when I was off sick), there was something deeply unsettling about it all – from the preachy tone, the thinly veiled judgement and the clear disdain for these people deemed “less than”. It made me feel like “my kind” were inferior and that our plight was simply for others’ amusement.

But as much as The Jeremy Kyle Show was deeply problematic, it wasn’t the only one of its kind. Schedules in the Noughties were plagued with questionable reality TV formats that took aim at the working class and those on the breadline, making fun of their suffering.

Overtly classist shows such as Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away (about High Court enforcement officers), Benefits Street (a “fly-on-the-wall” series about life on the dole), Grimefighters (about blue-collar workers with the lowliest jobs, cleaning up other people’s “filth”) and The Great British Benefits Handout – in which unemployed families were given a lump sum to come off benefits, to show how their lives would improve – purported to be exposés about the state of the country. But by highlighting this extreme poverty on national TV in this way, they so rarely helped people stuck in those situations – and instead made them public targets.

Perhaps less obvious and far more insidious were the likes of Wife Swap, The Secret Millionaire and Holiday Showdown. On the surface, these programmes may have seemed harmless, but deep down there was a voyeuristic element of them, a disturbing fascination with those not well off.

The extremely rich cosplaying as commoners? Middle-class families “slumming it” on a trip to Benidorm and forgoing their usual five star resort and business class flights? How did these shows make it through quality control?

Of course, people will say that times have changed and this sort of thing was just “the norm” back then. And yes, that is quite evidently true – The Jeremy Kyle Show would never be commissioned today. But isn’t that also just a convenient excuse to wash our hands of our less-than-commendable past?

Don’t get me wrong, I am glad tastes have shifted and the entertainment industry has made some steps towards progress, but that doesn’t absolve it – or viewers, who lapped up this type of TV, and who still make casual comments about the type of clientele that went on The Jeremy Kyle Show – of its sins.

Collectively, we need to acknowledge this dark period in our TV history and vow never to make the same mistakes again. Because, ultimately, these people are human and not just entertainers there for our amusement. Equally, our comments about those on our screens have real-life consequences – as we have seen time and again.

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call or text 988, or visit 988lifeline.org to access online chat from the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. This is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If you are in another country, you can go to www.befrienders.org to find a helpline near you