Phil Hendry,Senior producer, BBC News

BBC

BBC“The worst decision of my life,” reflects Richard Moore, as he sits in the small flat he bought as an investment to provide him with a pension in his old age.

“My service charges have doubled from £4,000 to £8,000 a year. I feel like I’m being robbed”.

Problems with the building’s cladding also render the flat effectively worthless unless it is fixed, he says.

The flat Richard paid £300,000 for in 2016 is leasehold – which means he doesn’t own the physical flat – but a lease allowing him to own it for a specified number of years.

A freeholder owns the physical building and the land it’s built on, and employs a managing agent to act on their behalf and collect services charges to cover the cost of maintaining and insuring the building.

The managing agent says the increase is justified because the roof needs repairing. Richard points out the flats are less than 10 years old.

Reforms to leasehold and freehold became law on Friday – one of the last pieces of legislation to make it through Parliament before it was shut down for the general election.

They will help the estimated five million leasehold property owners – the vast majority of them in flats in England and Wales, the only countries still to operate the leasehold system.

It will make extending their leases cheaper and simpler with a standard 990-year lease on renewal.

There is also a duty on managing agents to be more transparent about their costs when billing leaseholders for service charges and maintenance. Richard’s say they already are, although he disagrees.

Missed opportunity?

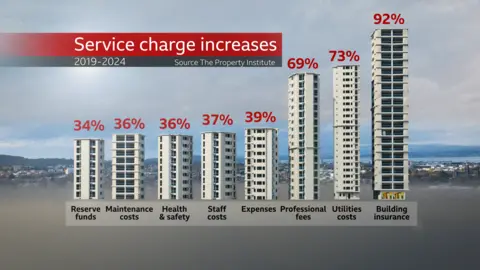

According to The Property Institute (TPI) – the trade body for managing agents – service charges like Richard’s have risen by over 40% in the last five years, but just 4% in the last 12 months.

“We have got above-inflation increases in service charges and that comes as no surprise to any leaseholders,” the TPI’s Andrew Bulmer says.

“Some service charges have gone up a moderate amount, but there are some, especially those in tall and complex buildings that are difficult to insure, where the service charges have rocketed and those individuals will certainly be hurting.”

Mr Bulmer denies managing agents are making excessive profits saying “margins are tight”.

He points to TPI data which suggests the only cost that has not seen above-inflation rises is the fees managing agents charge to cover their own admin and running costs.

Mr Bulmer suggests the new legislation is a missed opportunity for proper regulation with penalties for managing agents who step out of line.

“What regulation would do it wouldn’t just regulate technical performance in terms of transparency or publishing information. But it starts to regulate behaviours and when you regulate behaviours, you start to introduce trust in the relationship between the service provider and the customers.”

PA Media

PA MediaThe TPI data suggests the biggest single factor driving up service charge costs are buildings insurance premiums – up 92% in five years.

Insurers say that in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire and the subsequent cladding and building safety crisis they have no option.

“We empathise with the plight of leaseholders and the fact that they’re under emotional and financial strain and we are doing all we can to support that,” says Mervyn Skeet from the Association of British Insurers.

However, he adds: “I think the industry is correctly pricing the risk that’s there.

“Unfortunately, the risk wasn’t known in the same way prior to the tragedy at Grenfell. Now, the risk is well known.”

But premiums are still going up year on year despite government pledging several billion pounds to remove flammable cladding and other building safety issues.

The new leasehold laws will also restrict insurance brokers’ ability to charge large commissions for writing the policies, which it is claimed some managing agents have passed on to leaseholders with an additional administration charge of their own.

All the tower blocks with the same cladding as Grenfell have now been fixed, according to government figures.

Mr Skeet said the government was only fixing buildings to what he called a “life safety” standard – so that people could escape – but the insurance industry had to go further.

“Getting buildings to a life safety standards is obviously very important,” he said.

“But we need to assess the resilience of the building, price for the cost of the whole building being lost.”

Many insurers became more risk averse following Grenfell, refusing to provide cover for tower blocks with safety issues.

The government has been putting pressure on the industry over soaring premiums charged by those still prepared to take on the risk.

As a result, insurers have just launched a new scheme which aims to better share the risk of the most dangerous blocks which have yet to be repaired – of which there are still several thousand, according to the End Our Cladding Scandal campaign.

Mr Skeet said: “We hope to see that scheme having an impact over the next 12 months.

“The capacity in the market and the basic supply and demand should lead to changes in premiums.”

Among those as yet unremediated flats with cladding and safety issues is Richard’s in Croydon.

His experience means he thinks fewer and fewer people will consider ever buying or living in a leasehold property.

“It’s affecting millions of people in this country. I’m not the only cladding hostage out there.”