By Jonah Fisher, BBC Environment correspondent

BBC/Tony Jolliffe

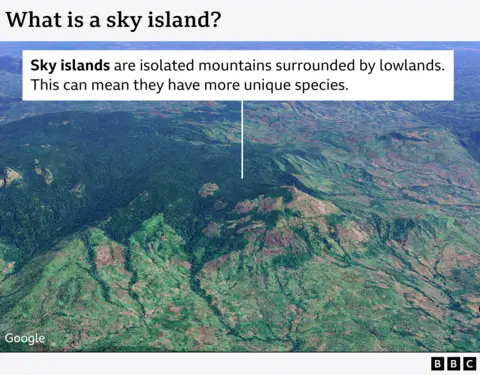

BBC/Tony JolliffePerched on a remote mountain top and surrounded by lowlands, Mabu is what’s known as a “sky island” and is the largest rainforest in southern Africa. BBC environment correspondent Jonah Fisher went to Mabu with a team of scientists who have discovered dozens of new species there, helping to convince Mozambique to protect it.

“Let me get my magic spoon,” Dr Gimo Daniel says with a smile.

It’s hard to imagine anyone taking more delight in their work than the 36-year-old Mozambican beetle expert.

We’re crouched around a small hole in the dirt not far from our camp in the centre of Mabu forest. Dr Daniel’s mission, like that of almost everyone on our expedition, is to find things that science has not seen before.

Dung beetles are Dr Daniel’s specialty and he chuckles as he pulls out a big plastic tub of bait – his own faeces.

The smell is as you’d expect. Pungent and impossible to ignore.

Dr Daniel tells me that he has already discovered what he believes are 15 new species of dung beetles.

“They can smell it up to 50 meters from here, so they come as fast as they can,” he says. “It’s brunch.”

Twenty years ago, Mabu was a secret to all but the locals.

It was ‘discovered’ for the outside world by Prof Julian Bayliss in 2004. An explorer and ecologist who now lives in north Wales, he was surveying satellite images of northern Mozambique when he came across a previously unknown dark green patch.

A first expedition the following year confirmed that although locals had been hunting in the forest it was in incredibly good condition and its size at 75 square kilometres made Mabu the largest single block of rainforest in southern Africa.

“I was like – oh my God – this is phenomenal,” Prof Bayliss recalls.

Tim Brammer

Tim Brammer BBC/Tony Jolliffe

BBC/Tony JolliffeIn early expeditions to Mabu, one of which I joined in 2009 while working as a BBC correspondent in southern Africa, Prof Bayliss was at the forefront of a ‘gold rush’ of discoveries, quickly finding several new species of chameleon, snake and butterfly.

In all Prof Bayliss says they’ve found at least 25 new species, and that’s not even counting the dung beetles, many of which still need to be officially recognised.

What makes Mabu so special is its geography. A medium altitude rainforest, it protrudes above Mozambique’s lowlands, makes it effectively a ‘sky island’.

That means most of the animals and insects that live there have no way of meeting and breeding with other populations, increasing the chances of them evolving in isolation into something unique and new to science.

The expedition the BBC joined this year at Prof Bayliss’ invitation was the first time a team of scientists had based themselves right in the centre of the forest.

Mabu was in part protected by Mozambique’s long history of civil war. The longest of which ended in 1992. It was also helped by the fact that it’s just so hard to get there.

After driving five hours along dirt roads all of the camping gear, food and equipment is loaded on to the backs and heads of more than sixty porters.

While we, and the scientists, adjusted our walking boots and dropped hydration salts in our water bottles, the porters, many of them wearing just flipflops, marched up Mount Mabu’s steep slopes.

Tony Jolliffe

Tony JolliffeOne of the first to find something new is Erica Tovela, a freshwater fish expert from Mozambique’s Natural History Museum. In the stream that runs through camp she catches a type of small catfish she’s not seen before.

“I hope that we have a new species for this area,” she says with a smile as she holds up a see-through bag of dead fish. (They will be preserved in formaldehyde for further analysis and comparison with other similar species). “Amazing. It will be the first new species for me.”

The process of definitively identifying a new species can take years. It involves writing a peer-reviewed paper in a journal in which the differences between the new discovery and its closest relatives are outlined and accepted by other scientists.

The next step for Ms Tovela is to get the DNA of her fish analysed and detailed descriptions and images circulated. And what might be the name?

“It should be something mabuensis,” she says. “It’s a nice way of saying we have one specific species that’s from Mabu.”

Tony Jolliffe

Tony JolliffeMabu’s forest is in good condition but that’s not to say that some things haven’t changed.

The large mammals that once inhabited it like lions, rhinos and buffalos have all been hunted out, most likely for food during the war. Deforestation has also taken a toll, though not as badly as other forests in southern Africa.

“It’s very visible that forests (in southern Africa) that I’ve been to just 15 to 20 years ago have now disappeared, cut down for many different reasons,” says Prof Ara Monadjem, an expert in small mammals from the University of Eswatini, who was on the trip.

At Mabu the deforestation has so far been limited but locals are certainly hunting. Camera traps show hunters carrying animals they’ve caught and we see physical traps made from car springs set just off the tracks through the forest.

But at the same time species of smaller mammals are also being discovered. They included a horseshoe bat called Rhinolophus mabuensis and a dwarf musk shrew which scientists are still in the process of naming and describing.

Ara Monadjem

Ara Monadjem Julian Bayliss

Julian BaylissNot everyone on the expedition is looking for new species. Bird experts Claire Spottiswoode and Callan Cohen have a very specific mission. To find evidence that one of Africa’s rarest birds is still alive.

The Namuli apalis only lives at altitude and there are fears that a combination of the destruction of forest elsewhere and warming temperatures are pushing the small yellow and black bird towards extinction.

Ross Gallardy

Ross Gallardy“Climate change often has these effects that are hard to predict,” Callan Cohen explains pointing out that sometimes warmer temperatures encourage snake activity, which means more nests and chicks come under attack.

Trying to find the rare bird involves playing it a recording of a Namuli apalis through a Bluetooth speaker and then waiting to see if any respond.

BBC/Tony Jolliffe

BBC/Tony JolliffeThere’s no sign or sound on the day that we join the search, but several days later the bird experts return to camp late at night bringing with them good news.

They managed to record sound of the Namuli Apalis on one of the higher ridges.

“It’s still a little concerning, to be honest,” Dr Cohen says of the huge effort it had taken.

Tony Jolliffe

Tony JolliffeSo what happens next? For Mabu, at least the signs appear positive.

Pejul Calenga, the director general of Mozambique’s conservation areas, tells me in an interview that Mabu is to be turned into a community protected area.

That will mean no logging or mining is allowed but that the locals who depend on the forest for their livelihoods will manage and be able to use it.

Of the role played by the scientists’ work in getting the area protected, he says: “It’s much easier to stand up for those areas in which we have unique resources present.”

Mr Calenga said Mabu now forms part of Mozambique’s commitment to a global biodiversity pledge to protect 30 percent of its land by 2030.

Having led so many expeditions into Mabu forest Prof Bayliss is cautiously optimistic that if the management plan is done well Mabu will turn into a conservation success story.

He’s already looking elsewhere in Africa for other sites that need protection.