Google users have a question: who pays for tariffs?

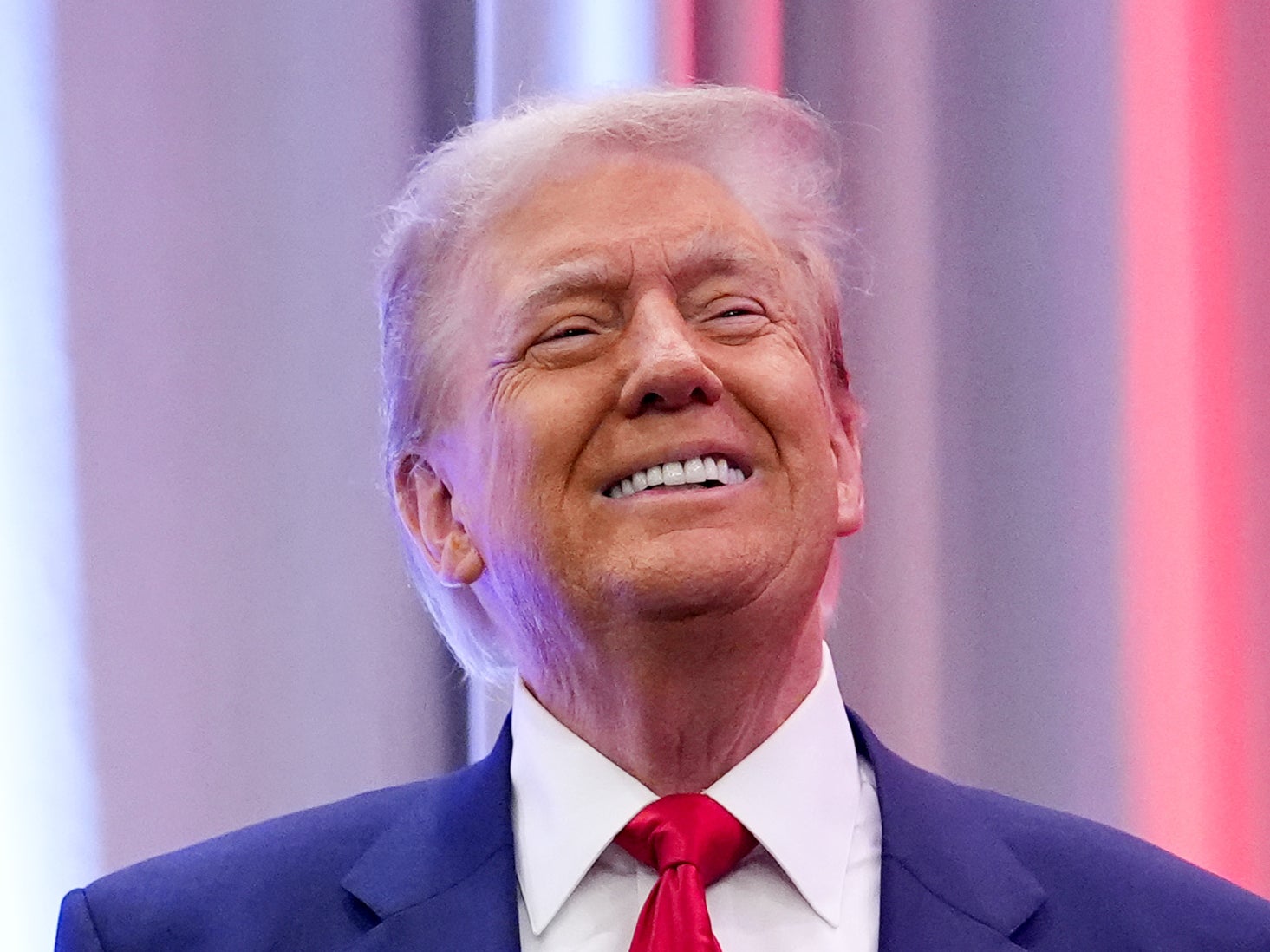

The phrase exploded in Google searches in late October and saw a massive spike again on Monday night. Those searches are no doubt driven by Trump’s insistence on levying tariffs on foreign-made goods. It appears a lot of people voted for Trump, but only thought after the fact to understand what those tariffs might mean for their wallets. It appears the same thing happened again this week after the president-elect announced new tarrifs.

Trump vowed that he would enact a 25 percent tariff on products from Canada and Mexico, and a 10-percent tariff on Chinese made goods — acts that would likely raise the prices of everything from basic consumer goods to high-end electronics to lumber for homes and commercial buildings.

President Claudia Sheinbaum has warned that if Trump tariffs Mexico, the nation will issue its own tariffs against the United States.

In Canada, President Justin Trudeau said he planned to hold an emergency meeting to discuss Trump’s tariffs.

But back at home, regular folks are just trying to figure out who is going to be paying for the increased costs.

Trump has insisted that he will force the nations he’s taxing to pay for the tariffs, but that is not how tariffs typically work. His past attempts at using tariffs to bolster American production and job growth yielded no positive results and some negative blowback from retaliatory taxing.

Most economists feel that tariffs are ultimately self-defeating.

During his last administration, Trump issued tariffs on steel and aluminum coming from the European Union in an effort to bolster U.S. materials production and bring back manufacturing jobs. The European Union responded by issuing tariffs against U.S. products such as bourbon and Harley-Davidson motorcycles, according to PBS.

China did similar — it tariffed American-made products including soybeans and pork.

A study conducted by economists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Zurich, Harvard, and the World Bank found that Trump’s first attempt to use tariffs “neither raised nor lowered U.S. employment.”

The researchers found that China’s retaliatory taxes actually had a “negative employment impact” that especially hit farmers, who Trump courted during his 2016 presidential campaign.

According to a 2021 analysis from the Tax Foundation, Trump’s 2018 tariffs actually raised prices for American consumers, and there is no reason to expect that it won’t happen again if Trump follows through on his plan to tariff foreign-made products.

Economists Pablo Fajgelbaum, Pinelopi Goldberg, Patrick Kennedy, and Amit Khandelwal analyzed Trump’s 2018 tariffs on products like solar panels, washing machines, steel, aluminum, and EU/Chinese goods and found that U.S. firms and consumers bore the brunt of those costs.

They estimated that the U.S. economy suffered a net loss of $16 billion annually, including more than $114 billion in losses to firms and consumers. Those losses were only slightly offset by minor gains for protected producers and a small revenue bump for the U.S. government.

Ultimately, the answer to “who pays for tariffs” is U.S. consumers and businesses. U.S. businesses have to pay the U.S. government for their foreign purchases. They then pass along that cost to consumers by way of higher prices, meaning they do not stimulate job growth and shrink Americans’ purchasing power by kicking up prices.