A week ago today, tickets for one of the most anticipated gigs of the decade went on sale.

It was expected to be a sell out – with the story afterwards sure to focus on the lucky fans who got in, and the unfortunate ones who missed out.

Instead, the ticket sale descended into anger and frustration – and brought a spotlight to an increasingly common business practice; dynamic pricing.

What is dynamic pricing?

Dynamic pricing – sometimes called surge pricing – is where the price of a product or service changes based on the level of demand. This is generally done automatically by a computer programme that tracks a number of factors – such as the number of users looking to buy and the number of products available for sale.

Imagine there are only 10 copies of a book left on a website, initially priced at €10 each.

If 100 people were to suddenly try to buy a copy at the same time, a dynamic pricing system would recognise that demand out-stripped supply and push the price of each book higher. This is an attempt to find the ‘market value’ of the book – essentially, in this case, the highest possible price that ten buyers are willing to pay to own the product.

It doesn’t matter if the vast majority of the would-be buyers are priced out, as long as enough shoppers still think the price is reasonable.

In theory, dynamic pricing can also work the other way – with the price of a product falling where demand is low.

While this does happen in some cases, dynamic pricing is generally noticed when it leads to prices going up.

Is this a new idea?

No, not at all.

The dynamic pricing model has long been used in a number of industries – including aviation and hospitality.

Consumers are used to airlines raising ticket prices as the number of seats available on a flight falls. Booking a seat well in advance also, generally, ensures a better price than if a customer waits until the last minute.

Hotels also tend to follow this approach – raising rates when fewer rooms are available, or when there is a sudden spike in demand for a particular date (like one that coincides with a big event or concert).

Where a flight or hotel has spare capacity hours or a day before, they may also drop their prices and allow a canny customer to bag a last minute deal.

In more recent years, though, the dynamic pricing model has begun to creep into other areas of business.

Online retailers like Amazon sometimes uses dynamic pricing to find the “best” price at which to sell a product.

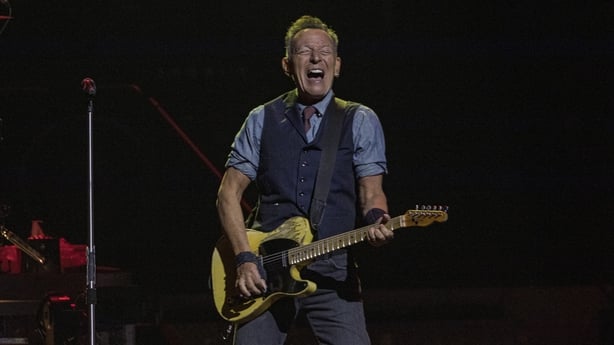

It’s also become a common feature of big gigs in the US, with music acts including Bruce Springsteen, Beyoncé and Harry Styles using it for their concerts.

Meanwhile, in the likes of the US and UK, ride sharing platforms like Uber and Lyft also use dynamic pricing.

This tends to see the cost of a trip rising during rush hour, when there are more people looking to hire a driver.

Is it legal in Ireland?

In the case of ride sharing apps, no.

That’s because anyone who is offering to transport people in return for money in Ireland has to have a ‘small public service vehicle’ (SPSV) licence – like a taxi or hackney driver.

They also have to adhere to set rates for taxi journeys. While those rates do rise slightly for peak hours journeys, it does not allow for the ‘dynamic’ style pricing used by these apps in other countries.

Outside of taxis, though, there are relatively few restrictions on pricing. That means dynamic pricing is, broadly, legal.

One key rule that does apply in all cases is that companies make the price of goods and services clear to consumers before they are asked to pay.

In the case of Ticketmaster and the Oasis concerts, consumers were shown the price before they confirmed their purchase and made their payment. That means this particular rule was, technically, followed.

However there are still questions around the way dynamic pricing was used in this case – which has prompted the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission here to launch an investigation.

In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority is conducting an “urgent review” of the practice, highlighting the need for firms to be “fair and transparent”.

The fact that fans were not told dynamic pricing would be used in advance of the ticket sale is likely central to that probe.

Meanwhile the European Commission is also set to look to see if Ticketmaster’s use of the pricing model to ensure it was compliant with EU law.

That could include a failure to give consumers enough information before they were given the option of buying tickets.

There are also rules against a dominant company imposing ‘excessive’ prices on customers.

Whatever about the law, is it fair?

Defenders of dynamic pricing for gigs say that pushing up the cost of in-demand tickets helps to deter touting, as it becomes harder for them to make a return on their purchase.

It also means that the artist is the one to benefit from the higher price, and not the reseller.

However, given the existence of anti-touting laws in Ireland and improvements in ticketing technology, touting has already become less attractive.

Another justification for dynamic pricing is the fact that concerts are increasingly becoming the main way that artists can make money.

Streaming services mean that single and album sales are no longer the money-spinner they once were – with Spotify and Apple Music only paying fractions of a cent per listen.

As a result, singers and bands need to make tours as lucrative as possible in order to make a return on their popularity.

This shift in the music industry is also the reason for the growth of ‘premium’ and ‘VIP’ ticket packages – which may offer added perks or a better spot in the venue.

But this also highlights an important point – the use of dynamic pricing, premium access and VIP ticketing is entirely at the discretion of the artists and the people around them.

In the case of Oasis, they claimed to be unaware of the plan to use dynamic pricing – instead shifting the blame onto their management and promoters.

However they are also likely to be big beneficiaries of the higher prices that fans paid.

Could it be banned?

Potentially, but doing so could have unintended consequences.

An attempt to impose a blanket ban on dynamic pricing would likely impact the aviation and hotel industries.

But even a more targeted approach would need to be done with care.

This week Fianna Fáil Senators Timmy Dooley said he would put forward legislation which would ban dynamic pricing for tickets at cultural, entertainment, recreational and sporting events.

The finer details of that bill are yet to be debated, but any rules would need to avoid breaching the EU’s internal market freedoms.

If dynamic pricing was banned here but remained legal elsewhere it could also make this country a less attractive destination for big artists – as they could potentially make larger profits from a gig in another country.

However some have suggested that smaller changes could limit the impact of dynamic pricing – or at least better prepare consumers for what it brings – without having to make a major change to consumer law.

At present, gig promoters are required to advertise the starting price of a gig’s tickets – excluding the additional charges that apply. Generally, though, even where dynamic pricing is not used, many of the tickets available at a concert are in higher price bands.

Requiring promoters to detail the price of all tickets – or at least a price range – would go some way to improving transparency.

Asking them to detail how many tickets are available at each price point would be even more beneficial to would-be buyers.

Meanwhile, politicians in the US are currently debating a legislative change that would require the clear display of the full ticket price – inclusive of taxes and charges.