When Naomi Campell made her entrance on the Cannes red carpet last month, it was a bit of a statement. Sure, she was working with image architect Law Roach, which was notable in its own right. And she looked absolutely stunning as she prepared to mount those 24 red steps. TBut the look hinted at a story.

The supermodel chose an archival dress for the event. The all-black look featured The all-black look featured alternating sheer and sequin panels and was held up by delicate pearl shoulder straps. It debuted on Chanel’s couture runway back in 1996 designed by Karl Lagerfeld and was worn by the model Campbell herself. and was modeled by Campbell herself. To wear it again, almost 30 years later, was a direct testament to her enduring influence in the fashion industry.her enduring stature in the fashion industry. It pays tribute to her unparalleled legacy as a fashion model, built in the face of industry biases, including racism, and showcases a body of work paid tribute to her unparalleled legacy as a fashion model with a body of work possessed by no other, built in the face of industry biases, including what was often explicit racism.

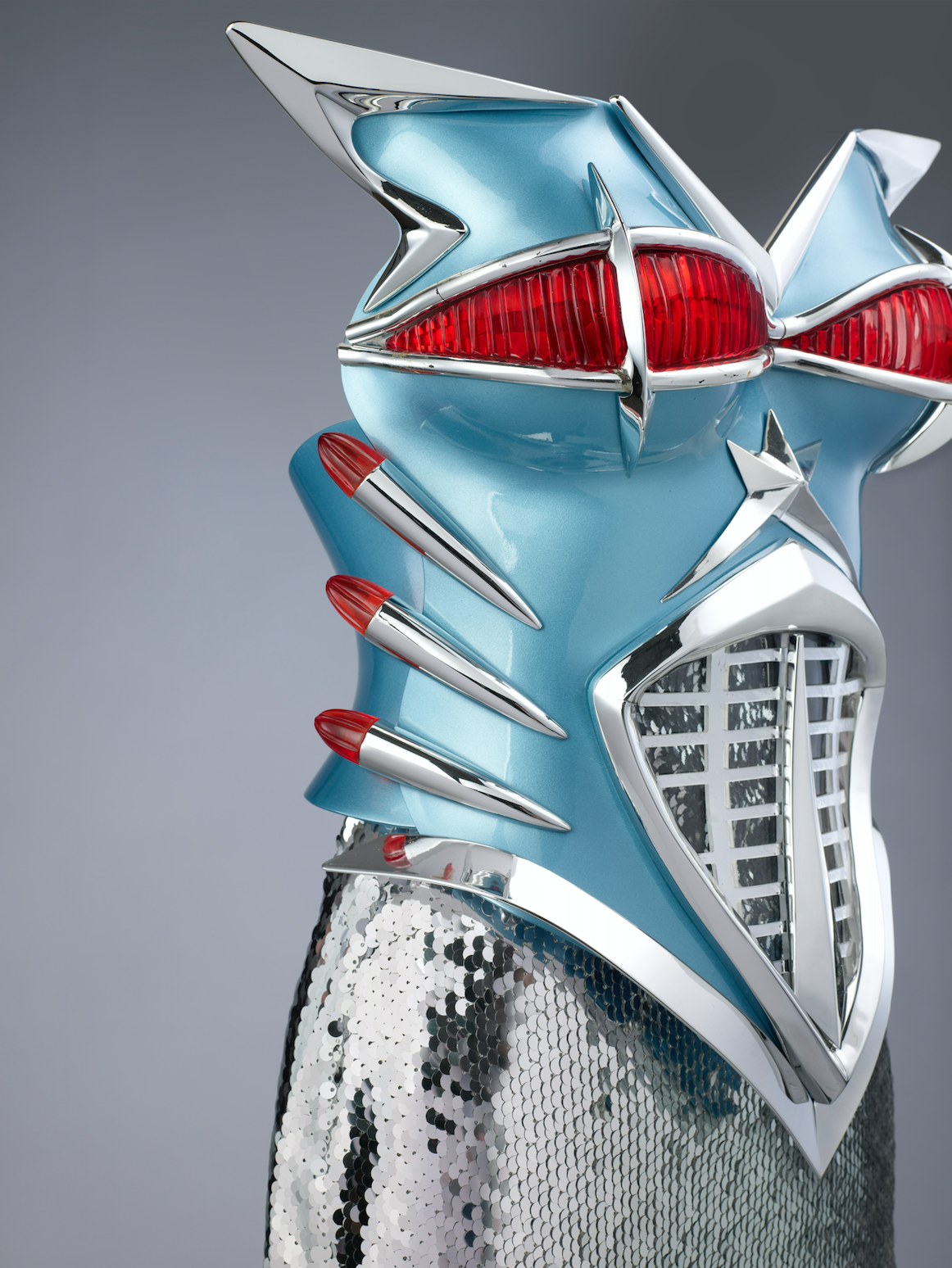

“I was told many times that I couldn’t do certain things because of the color of my skin, but I never let that be an excuse — I let it drive me,” Campbell said in 2018 when she accepted her Fashion Icon Award, an honor bestowed by the Council of Fashion Designers of America annually. The British Fashion Awards labeled her with the same title in 2019. “They told me I would only last 11 years, but I’m here, and it’s been 32 years.” Five years later, she’s still working and walking runways for brands like Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen as well as Balmain. It’s all a part of a legacy to be commemorated this summer in a first-of-its-kind exhibit at the Victoria & Albert Museum in South Kensington, London simply called Naomi: In Fashion, which opens on June 22.

“She’s like an entity, a force. Someone who’s driven to be great,“ Bethann Hardison, the subject of the documentary Invisible Beauty who made history as a model before becoming a model agent and changemaker in the industry, tells Essence. Hardison met Campbell when the model was 15 years old and became a “second mother” to her. “[Her peers] have other lives. They grow up and move on. But for her, fashion has always been something that she’s been committed to in such an interesting way.”

Campbell’s story has been told many times: she was discovered as a model at age 15, and before she turned 16 had appeared on the cover of Elle UK in 1986, later booking a 1987 cover of British Vogue as the second Black woman to receive the prime positioning. Then there were the covers of Vogue Paris in 1988 (the first Black woman to cover the magazine,) American Vogue in 1989 (first Black woman on the September issue,) and Time magazine in 1991 (the first Black model to achieve that.) She was not only one of the original supermodels, but specifically in the powerful trio dubbed “The Trinity” in the 1990s, which included Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington. She was acclaimed for her exceptional ability, and rumors circulated that designers would have her showcase their most challenging or awe-inspiring pieces on the catwalk to ensure they received the attention and press they deserved.

To round out those first11 years of her career, she achieved several milestones, being the first Black model to star in a Prada campaign in 1994 and to open a Prada show in 1997. However, this was only the launching ground for a trajectory that has included more than 600 covers — including being on the front of our 50th anniversary issue — and in countless runway shows spanning nearly four decades.

“Naomi was part of this heyday of Black models in the 80s to the early 90s — there were so many incredible, gorgeous girls at the heights of fashion then,” Marcellas Reynolds, author of Supreme Models Iconic Black Women Who Revolutionized Fashion tells Essence. “But one thing I discovered while doing interviews for Supreme Models was that at the time, when Naomi really hit and connected with the business, she opened things up for other Black models. Now, clients who weren’t looking at Black models before, or were only looking at light skinned models, were looking at the entire spectrum.”

“She couldn’t do everything so she was partially responsible for the heyday,” Reynolds continues of that period in the late 80s and early 90s. “She created a need for Black models almost single-handedly.”

Campbell’s impact and legacy on the fashion industry, in this way, can be compared to the likes of Kate Moss and Gisele Bunchen. Except to compare them as peers, which they are in ways, ignores that Campbell’s career predates them both with the model appearing on Elle and Vogue covers before either of them had been scouted. And it’s unlikely that their fight was the same as Campbell’s.

“I always called her my Buffalo soldier because she was always fighting for arrival, fighting for survival,” Hardison says. Over the years, she’s teamed up with Campbell on multiple efforts like the Black Girls Coalition and the Diversity Coalition to effect industry change. According to her, the stunner has always cared about what goes on behind the scenes. “She has that spirit.”

Naomi has long discussed her issues in the industry. Her first French Vogue came because Yves Saint Laurent threatened to pull his advertising. She began to be cast in runway shows for brands like Helmut Lang as well as Prada only because fellow supermodels Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington mandated that all three were booked or none would walk. And while those were steps, the massive multi-year beauty and fragrance ambassador contracts that many of her contemporaries secured eluded her — she notably signed her first beauty contract in 2018 with Nars Cosmetics.

“Those girls had the option to step out of the industry if they wanted to, while Naomi almost had to keep working.” Reynolds says. “You have like Christy Turlington who had a multi-year Maybelline campaign making millions and millions of dollars which allowed her to stop working and pursue other things in her life. I don’t know that Naomi had that safety net they had.”

So Campbell worked on, beside generations of women she had posed as a possibility model for, amassing a legacy that has touched almost every major name within the industry. As the V&A exhibit attests, she has become inextricably linked to the success of multiple designers including names like Marc Jacobs, Anna Sui and Zac Posen in addition to posing as a muse for the likes of Alexander McQueen, John Galliano and Azzedine Alaia. She is no simple mannequin but has, throughout her career, been actively involved in the industry, in her latter years not only mentoring models but leveraging her visibility to bring attention to emerging markets and designers out of Africa. And it’s work that she has done consciously, uniquely aware of the power of visibility.

“This whole exhibit happening, this was all Naomi,” Hardison says. Naomi: In Fashion is the first major exhibit show dedicated to a single model and the first at V&A dedicated to a Black woman. “I think people look at it and think ‘look what the V&A is doing for Naomi, that’s so great of them’ but Naomi was talking to me about wanting to do this when she was in her 20s. She would tell me back then, ‘Ma, I want to do an exhibit of the clothes I have from over the years.’” And now she has.

Just a taste of the one-of-one force that is Naomi.