The screen is black. Moby, on the other side of it, and on the other side of the Atlantic, prefers to do interviews off camera these days. But I think I can say with certainty how he looks – square glasses, no hair, probably a T-shirt – and I know for sure that his right arm bears the word “ANIMAL” in permanently inked block capitals, with a matching “RIGHTS” tattoo on his left.

The 58-year-old has been a global music star for decades – his 1999 album Play was a multi-platinum smash across the world – but, as he tells me now, the fight to end animal suffering and reverse climate change is where his focus is currently. “I’ve simply stopped seeing music as a job,” he says. “Activism seems like the only good use of my daytime quotidian work life. And then at night, I work on music and that’s the refuge where I get to just breathe and enjoy time spent being creative.”

His collaborative project always centred at night, out this week, is one of the fruits of that creative space. It has led to an album on which Moby provides the musical backdrop to songs sung by a diverse set of artists that ranges from Lady Blackbird to serpentwithfeet and Netherlands-based singer Gaidaa to British poet Benjamin Zephaniah, who died in December. “I’d never heard him do spoken word poetry,” Moby says – the two knew each other as vegan activists – yet their drum’n’bass collaboration, “where is your pride?”, is a revelation.

There’s a lovely cover, too, of Cream’s “We’re Going Wrong” by Moby’s friend Brie O’Banion. Most of the other featured singers are artists of colour. I wonder if Moby, who has been criticised in the past for using some of the Black voices he sampled on Play (such as 1930s folk singer Vera Hall on “Natural Blues”), was conscious of this when choosing his collaborators. “It’s such a complicated, nuanced, cultural, creative, semiotic minefield,” he says, “all I do is sort of stumble through and try to be guided by a desire to make music that I love. And, as we know, in this part of the 21st century, you can’t do anything without offending someone. And I know some people are paralysed by that to the point where either they only create the most anodyne work, or they make nothing.” His criteria for working with someone, he says, “is simply the emotional quality of their voice”.

He’s at his home near the Griffiths Park Observatory in Los Angeles. Moby used to live in a 12-bedroom Hollywood castle called the Wolf’s Lair, but downsized a decade ago from what he has described as his “Gatsby-esque/Citizen Kane” existence after realising that he spent almost all his time in a handful of small rooms. He lives alone.

“The last relationship I had was about 10 years ago,” he says, “and when the relationship ended – and you can happily dismiss it as me being a self-involved, delusional, narcissistic Angeleno – but there was this little voice that I heard that said, ‘Yeah, it’s not your lot in life, to have a normal relationship.’” There have been quite a few over the years, including, in the 2000s, Lizzy Grant, who would become a pop star herself as Lana Del Rey. Dating often gave him panic attacks.

He realised the things that were important to him in that moment – philanthropy and politics and creativity – but that little voice was wistful, he says. It was talking to him about “the world of relationships, marriage, family, children… almost like it was patting me on the back to say, ‘Sorry, that’s not for you this time.’ I was like, OK, there’s a sadness to that, but it also is borne out by my experience. And it just sort of makes sense. So as a result, in 10 years, I haven’t gone on a date or even pursued one”.

As someone who in his autobiography described his promiscuity as “a thing of legend” in Noughties lower Manhattan, surely Moby misses sex? Or even intimacy? “No, that’s the only thing that’s strange – that it’s not strange,” he says. “It’s glaringly obvious we live in a world where everyone’s obsessed with every aspect of relationships and intimacy. And it’s very strange, when you remove yourself – not for any virtuous reasons. I’m not part of a monastic order. It’s more just rational empiricism saying, OK, I guess it’s no longer a part of my life.”

The man we know as Moby was born Richard Hall in Harlem. His mother told him he had been conceived to the sound of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. When he was two years old, his father got drunk after a marital row and drove his car at 100mph into the base of a bridge on the New Jersey Turnpike and was killed. “Friends of mine who lost siblings or parents when they were adolescents, it devastated them, and they’re still affected by it,” Moby says. “But I don’t remember ever having an emotion around it.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

When he reached the age that his father was when he died, though, his childhood image of his parents as adult entities gave way to a new understanding. “He died when he was 26. And when I turned 27, I realised he wasn’t a big demigod. He was a scared kid,” says Moby. “Not really that much of an adult at that point… just a troubled, scared, [drink]-addicted kid.”

His mother took her young son back to Connecticut, where she’d grown up, then to San Francisco, where Moby took a dislike to her “scary hippie” friends, and then again to Connecticut, settling in the small affluent town of Darien, where her family lived. Moby’s grandfather worked on Wall Street, but his mother struggled to make ends meet. Later, Moby would move back to New York himself, living in an abandoned warehouse on the Lower East Side as he played in punk bands and got work as a DJ on the underground club scene, often playing hip-hop. When he began releasing his own music, he had an early breakthrough hit in the UK with “Go” (1991), which sampled the Twin Peaks theme song.

There was this little voice that I heard that said, ‘Yeah, it’s not your lot in life, to have a normal relationship’

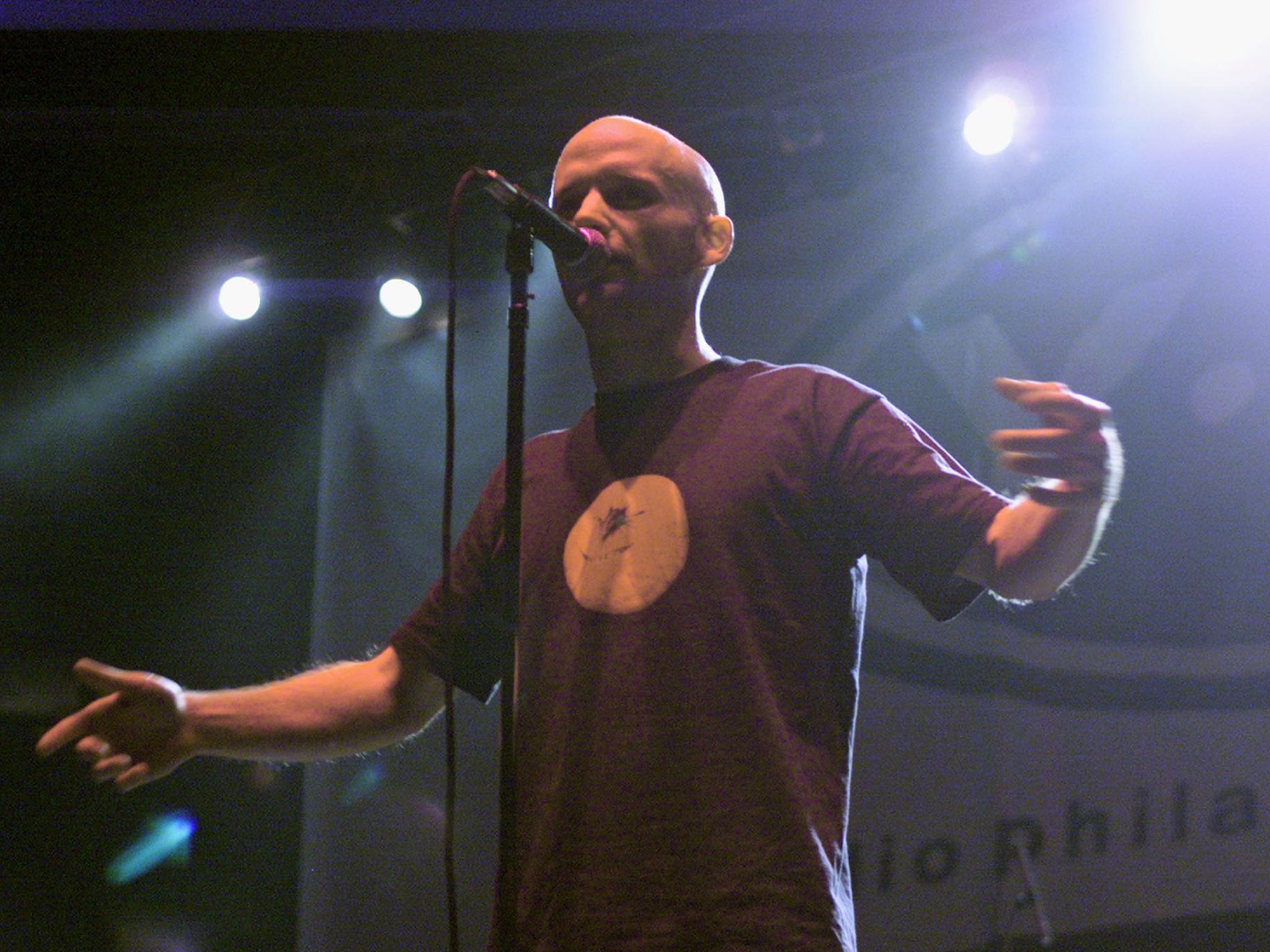

His euphoric live shows helped him to cross over – in 1993, Melody Maker called him “a consummate showman/shaman” on stage as well as a hyperventilating adrenaline junkie. But it was with Play in 1999 that he became a superstar. The enduring track “Porcelain” provided the title of his first memoir in 2016; his second, Then It Fell Apart, published in 2019, took its title from a line in “Extreme Ways” from the album 18 (2002), which topped the charts in 12 countries. Moby’s music is as hard to categorise as the man himself, jitterbugging between genres, from ambient to punk to techno, but its melodic core makes it accessible to all.

Behind the success, though, was a jarring alternative history. Back in 1995, Moby told a music journalist that he was in such pain and anguish from a breakup that he had been getting drunk and going out to seek solace in uncommitted sex. Another reporter had turned up at his door to find him covered in black paint after a fit of rage, during which he daubed abusive slogans all over his walls.

By 2008, when he was releasing the upbeat Last Night album, substance abuse had led him privately into a dark place. “I was suicidal, and I was looking to buy a bar where I could drink myself to death,” he wrote in Then It Fell Apart. Today, he can see it clearly. “I was bottoming out as an alcoholic, bottoming out as a drug addict,” he says. “A lot of my friends take drugs once or twice a year, and it’s not problematic. Me, I took drugs a lot. And it was very problematic.”

The book spares few gory details. Moby relays a game he used to play with his friends called “knob-touch”, in which you had to take your penis out at a party and brush it up against someone without them noticing. Moby’s challenge was to “knob-touch” emerging reality TV star Donald Trump, which, with the help of a shot of vodka, he did in 2001.

Does he ever think, oh god, why did I put that out into the world? “There was a goal…” he begins, explaining how he had modelled the book on Moby-Dick and its existential vision, intending to show “what about us, as individuals, as a species compels us to make so many bad decisions in the pursuit of wellbeing and meaning?” The anecdotes and stories showed the brokenness that Moby had been trying to fix “with alcohol, drugs, promiscuity and fame”. Obviously, he notes, “it didn’t work”.

It wasn’t this passage that almost proved his nemesis, though. He wrote about briefly dating film star Natalie Portman, to which Portman responded with a blast that her recollection was of a “much older man being creepy with me when I just had graduated high school… He said I was 20; I definitely wasn’t. I was a teenager. I had just turned 18”. At first, Moby attempted to back up the claim, before publicly apologising for not speaking to Portman first. It was too late; social media turned on him.

“I did learn a very cold, hard-earned lesson, which is sort of the corrosive absurdity of handing your sense of self and your wellbeing over to the opinions of people you’ve never met,” he says – “which is not, you know, Natalie.” It reminded him that who he is “should be informed by things that are real: the things that are around you, your friends, your community, your creativity, your spirituality, your health. These are real things that should define who we are, as opposed to letting the opinions of at times millions of angry strangers affect your sense of self”.

Even Ricky Gervais, if he says something about trans people that I might disagree with, I’m like, yeah, but he is an animal rights activist

Does he stand by his memory of events? “In both of the memoirs, I did my best,” he says. Memory, he insists, whether you apply it to Nabokov or Proust, “is fallible. So, who knows? Memory is by definition inherently cripplingly subjective […] I will say, I did not knowingly misrepresent anything in both memoirs, but whether it’s objectively true or not, one could just argue that, from Descartes to Sartre to Wittgenstein, objective truth is denied us in human form”.

Success inevitably brought him into contact with other famous people, too, including icons such as his Manhattan neighbour David Bowie and his friend Lou Reed. Will we ever see their likes again? “I don’t fully trust my perspective, because as a 58-year-old guy, it’s potentially a little too easy for me to glorify the past,” he says. But what he will say is that a teenager listening to music now is likely doing 11 other things at the same time. “They’re on Snapchat and TikTok and they’re playing World of Warcraft, and they’re possibly caffeinated from Mountain Dew, but also taking Adderall.”

Is he in contact with other celebrity advocates for animal rights, such as Ricky Gervais and Joaquin Phoenix? “The vegan mafia,” he says, with recognition. “For the most part, we all do know each other, especially as I used to have a restaurant in LA called Little Pine. And at some point, everyone in the vegan mafia ate there, from Morrissey to Leo DiCaprio, to Kate and Rooney Mara, to Joaquin and Cory Booker. I’ve known Joaquin for decades. He occupies an incredibly precious special place… even Ricky Gervais, if he says something about trans people that I might disagree with, I’m like, yeah, but he is an animal rights activist. I still kind of revere him for giving money to animal rights organisations and being so outspoken about it.”

It’s his own passion for animal rights that has tempted Moby back on tour. This autumn, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Play, Moby is playing in the UK and Europe for the first time since 2011. It was only by agreeing to donate all the profits towards the causes Moby believes in that his manager convinced him to do it all. But he is promising a greatest hits set. Dance music’s great shaman/showman will surely be in his element.

‘always centred at night’ is out on 14 June via always centered at night and Mute Records; The Play 25th Anniversary tour kicks off in Manchester on 18 September, tickets here