“Everyone remembers their first Nokia,” says Mark Mason, who joined the telecoms company’s design team back in its 1990s heyday. “When you say the name, it evokes a memory.”

This is not as hyperbolic as it sounds – in 1998, the Finnish consumer electronics company was the bestselling phone brand in the world, with 40% of the world market and 70% of the UK market.

The cultural impact of Nokia will be properly recognised for the first time in January when the company’s design archive goes on display. Finland’s Aalto University has acquired the archive and will make it available through an online curated portal as well as putting it on display at its campus in Espoo.

While for Finland the impact of Nokia is indisputable – the Research Institute of the Finnish Economy (Etla) reports it contributed a quarter of Finland’s economic growth between 1998 and 2007 – the brand’s international pop culture value is undeniable, too.

“Nokia was one of the first phone companies to really emphasise design and difference, with everything from very affordable phones right up to the latest cutting-edge handsets,” says Jonathan Bell, tech editor for Wallpaper* magazine. “In the world before Apple, Google and even Samsung, they stood above all the other players.”

Nokia’s factory setting ringtone – the 1902 Gran Vals by Francisco Tárrega – was so ubiquitous in the 1990s and 2000s that birds learned to sing it. In 2009, it was reported that the tune was heard an estimated 1.8bn times a day around the world – the equivalent of 20,000 times a second.

The Nokia 8110 handset – more commonly known as the banana – had a starring role in the 1999 film The Matrix. The brand quickly became imbued with cultural cachet.

Style journalist Murray Healy worked at The Face magazine in the 90s during Nokia’s prime and is now editorial director at fashion title Perfect. “In the late 90s, when mobiles were these dull, serious, precious and expensive mini-monoliths associated with yuppies, this cheaper, curvy, happy-looking handset that looks a bit like a toy turned up,” he says. “It’s pocket-sized, the battery lasts for ever and it seems indestructible.”

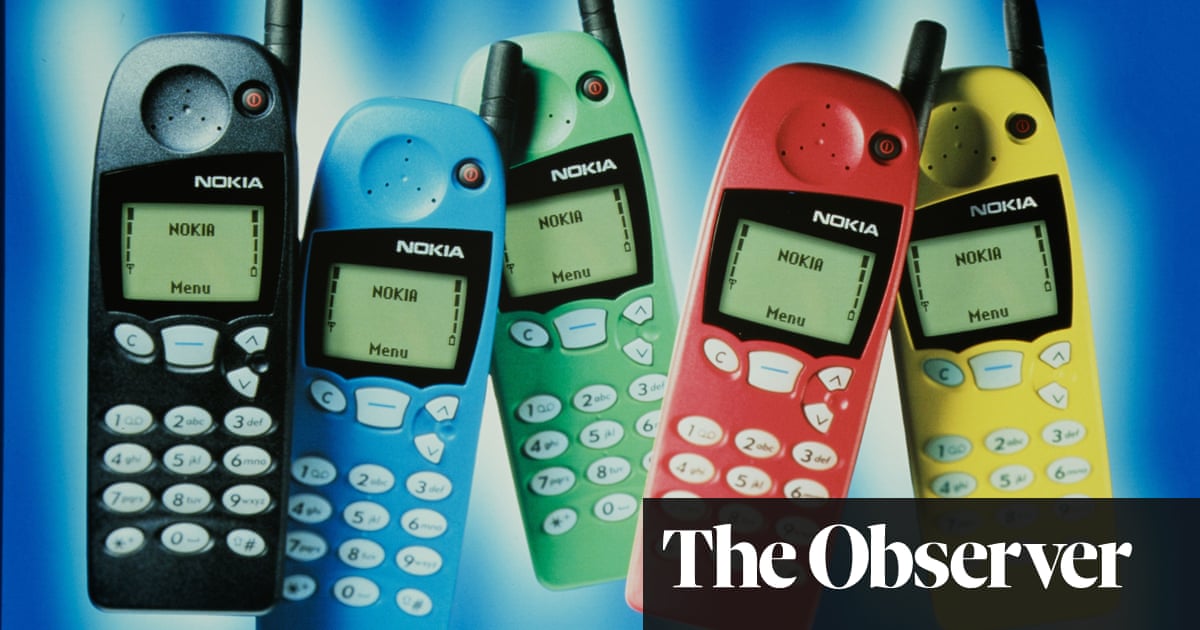

Healy says the Nokia 3210 – released in 1999 – was key as it helped to usher in a culture of complete customisation, with its colourful changeable casing. “You could even get your favourite band’s name printed on it.”

Nokia was also the first mobile phone manufacturer to support SMS texting, and the handsets’ keypads were perfectly designed for it.

“All these factors gave it immediate appeal for the youth market, who were already adept at getting round the prohibitive cost of phone calls by texting,” says Healy.

Mason, who worked at Nokia for 20 years and is now a design expert for the UK’s Design Council, says it was a fantastic time for creativity. “We created a design language early which put people at the centre. Our mantra was ‘human technology’ and Nokia’s slogan was ‘Connecting people’. Everything we did was around that. Even the keyboard was curved like a Mona Lisa smile. When you looked it, it smiled back at you.”

The Aalto University archive includes marketing imagery, sketches, market profiling and presentations providing new insight into what was once one of the world’s most innovative companies.

Anna Valtonen is lead researcher on the Nokia design archive and is a former designer at the company. Her favourite artefact in the records are audio tapes of designers describing what they’ve been working on. “In combination with the visual materials, it crafts a more human story. It not only gives colour to the documents, but it outlines what the designers were trying to achieve.”

Nokia’s operating profit was $4bn by 1999, but the ride was not to last.

after newsletter promotion

Ben Wood, chief analyst and marketing officer of CCS Insights, says: “It’s a sad story of a once great company that not only defined but dominated an industry for over a decade, only to disappear into oblivion faster than anyone could have possibly imagined.”

Nokia’s decline was down to a combination of factors. Complacency played a big role – the company failed to accept new approaches, particularly the competitive threat posed by more powerful touchscreen smartphones such as the iPhone.

From 2007 onwards, the market value of Nokia declined by about 90% and it was bought out by Microsoft in 2013.

The Nokia design archive is a window back to an optimistic time when personal devices and tech were seen as purely positive additions to family life and wellbeing. But its clunky, chunky phones are now finding a new audience among young people whose parents grew up with the brand and now want to give their children less social media access.

Nokia handsets have been back in production since 2016, made by Human Mobile Devices – HMD – a Finnish independent mobile phone manufacturer, largely staffed by former Nokia employees.

Valtonen said that working on the archive gave her more than a sense of nostalgia. “It made me feel more optimistic – and future-facing – than anything else. There are so many changes happening in technology at such a rapid pace that it’s great to stop for a moment and just get a glimpse of all the work that goes on behind the scenes. I hope the material inspires people and pushes them to see the possibility of innovation.”

Mason’s hope is more unashamedly nostalgic. “I can’t enthuse enough about my time at Nokia. It was like a family and we created design icons. I hope people dig their old handset out the drawer – they would probably still work. Cut me and I’ll bleed pure blue Nokia blood.”