For Lindsey Buckingham, making Tusk was akin to following Jurassic Park with some small indie cult flick. “Here we are in Spielberg-land,” he says of life after selling 16 million copies of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours in 1977, en route to its eventual 40 million global sales. “But if you’re willing to do what you want to do and lose nine-tenths of your audience, then you’re Jim Jarmusch or somebody. That’s what I’ve been valuing ever since Tusk.”

On its 1979 release, 45 years ago this week, Tusk was one of the boldest, bravest, and most bewildering records in rock’n’roll history, the very grandest of rock follies. Fleetwood Mac were following Rumours, the ninth-best-selling album of all time, with this experimental, often ramshackle double record full of junkyard clatter, Kleenex box drums and a full-on marching band. A record that was willing to risk the sort of monumental folk-rock success most bands can only dream of in order to stay creatively invigorated and relevant within an evolving post-punk landscape.

At the time, Tusk sold four million albums: a career-making phenomenon for most acts but a major knockback for Fleetwood Mac. However, as their late-Seventies era has been rediscovered and re-evaluated by subsequent generations, Tusk has become regarded as a triumph of art and creativity over the crass demands of mainstream commerce.

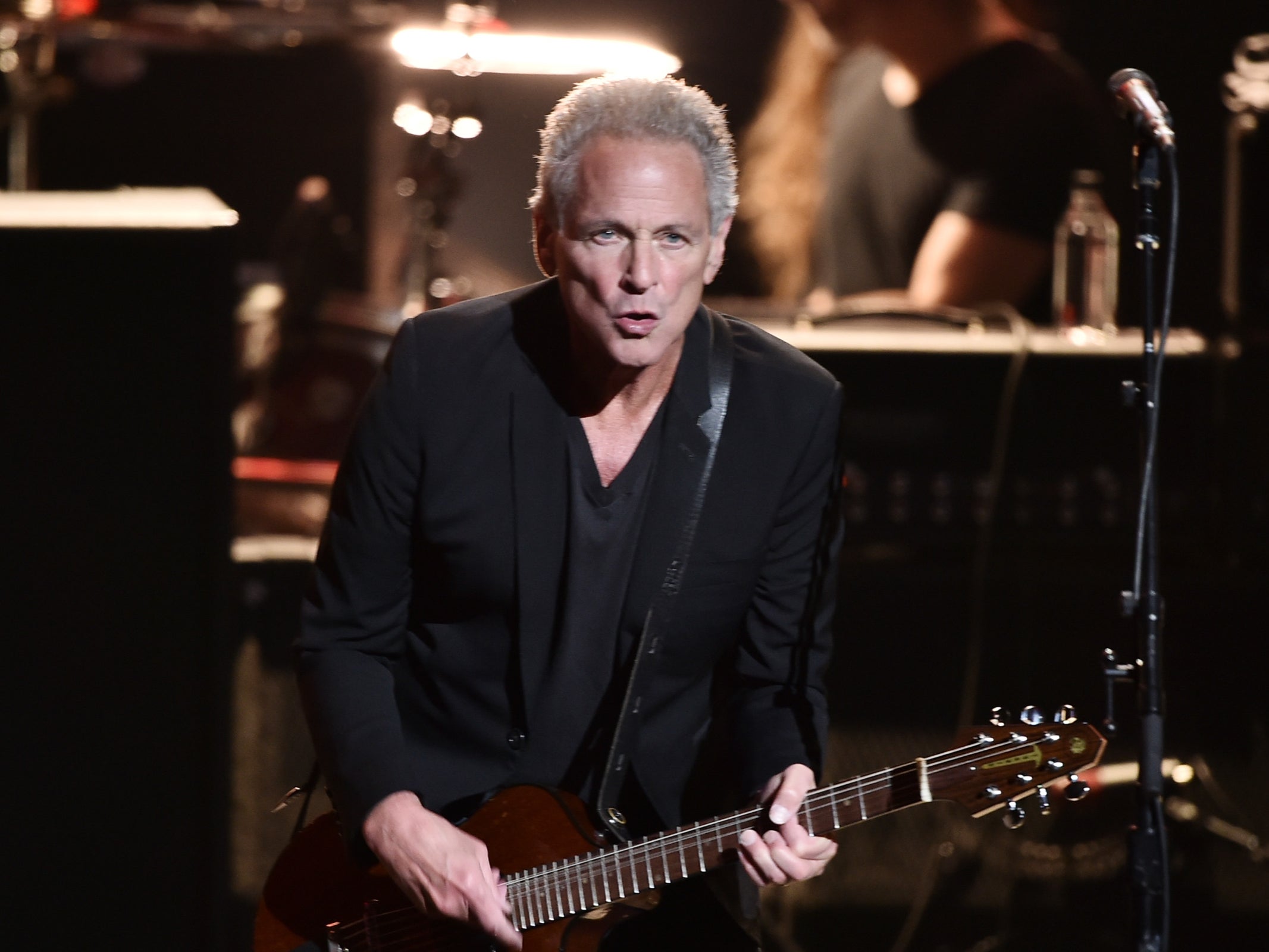

“There was a certain amount of esteem that it did garner from people who might have thought Rumours maybe a little too safe or a little too decadent or a little too California,” the former Fleetwood Mac singer and guitarist, now 75, says down the line from his Californian home, happy to discuss a record that acts as an origin story for his decades of musical exploration since. “But it did take a number of years for it to reveal itself. People, younger artists especially, began to appreciate it, not just for the creativity but for the reason it was done. They could see that there was a method to the philosophy of it.”

Tusk is arguably the most punk record of the Seventies; the ultimate in nonconformist, anti-commercial artistic expression with far, far more than a last-minute punt deal with Virgin Records on the line. For Buckingham, though – relatively fresh in Fleetwood Mac, having joined with then partner Stevie Nicks on New Year’s Eve 1974 and hit the biggest of big times on just his third album release – it was merely the natural next step of an artist following the instincts that were serving them so well.

“With our first album [1975’s seven-million-selling Fleetwood Mac] and then with the Rumours album, everything we’d done had been from our gut, from our heart,” he says. “And [Tusk] was where we wanted to go creatively and emotionally.” The inevitable “far greater, extreme expectations” from their label Warner Bros to repeat the formula of Rumours seemed counterintuitive: this was the Rumours formula.

“It was a spontaneous, authentic set of events that led to the creation of that album,” he insists. “If you then suddenly start to think more in terms of external expectations, and ‘Let’s do another song like that’, then you’re not really prioritising the creativity or the artistic outcome. You are prioritising the commercial outcome.” The danger, he says, is becoming a caricature of yourself. “You find a lot of artists who fall into that trap, and… maybe they lose the thread of their spontaneous impulses in terms of creativity. They lose the religion of it. And that was something that I was very determined not to do.”

Tinkering alone at the 24-track studio in his house, Buckingham was drawn back to what he describes as a more painterly approach to songwriting that he’d employed on 1973’s pre-Mac Buckingham Nicks album: “The Les Paul approach, where you play everything yourself and you’re bouncing tracks around.” He was also inspired by the creative fearlessness of The Beatles and The Beach Boys, as well as the jagged urgency of Talking Heads and their European new wave counterparts, a sound that spoke to the childhood rock’n’roll fan within.

“All the new wave stuff had come in from England and reinforced some sense of what the initial meaning of rock’n’roll had been when Elvis Presley first showed up when I was six years old,” he says. “There was an element of [new wave] that, to some degree, pitted people a bit against Fleetwood Mac at the time. But for me, it was actually something that helped me to find my bearings.”

Famously, Fleetwood Mac were a uniquely fractured family in the late Seventies, with two central relationships – Buckingham and Nicks; John and Christine McVie – splitting up around the writing and recording of Rumours. That record – featuring pointed songs like “Go Your Own Way” and “Second Hand News” – had acted as a raw, cathartic, and accusatory sort of post-relationship couples’ therapy.

Its making had been fraught with compartmentalised feelings compounded by a lack of healing distance. “In the midst of making Rumours, that [friction] hit its full throttle in terms of us having to go in the studio and make the right choices for each other as well as for ourselves,” Buckingham says. But the album’s success had highlighted the inherent magic in the band’s musical bond.

“We rose above our personal difficulties so beautifully in order to make [Rumours],” says Buckingham. “In doing that [we realised] we had a destiny that was more important and greater than all of us personally. When that album did succeed on the level it did, it just made us realise that our personal lives were one thing, but there was something more profound that was going on, and that it was our job to embrace that. In a way, I guess you could say that was galvanising.”

Certainly, Buckingham arrived at the now legendary Studio D in Los Angeles – built specifically for the band at Village Recorder studios – in 1978 with demos of cranky, angular, sped-up songs recorded in his bathroom, featuring beats knocked out on cheap drums and tissue boxes, to find the Mac receptive to his experimental vision for Tusk. “We had each other, and we were still calling the shots,” he says. “But it was still a fairly radical leap to take. I was lucky that I had bandmates who were open to me taking such a leap at that time… I don’t remember there being any sense of, ‘Oh, where’s your ‘Go Your Own Way’? There was a sense of release in doing something so different and I think it was catching.”

It was, to some degree, a fait accompli on the part of Buckingham. “He had already decided that he wanted to make a solo record,” Christine McVie told Uncut in 2015. “In order to keep him within the fold we all said, ‘Well, look, let him do his experimenting and incorporate it in the album somehow.’ That’s how in essence it came to be a double album.”

Split from Buckingham, Nicks had started seeing Mick Fleetwood – exacerbating tensions within the band – and the Tusk sessions have gone down in history as among rock’s most excessive. McVie remembered lobster, exotic foods, and champagne arriving at the studio by the crateload. “And it had to be the best, with no thought of what it cost. Stupid. Really stupid,” she said. “Somebody once said that with the money we spent on champagne in one night, they could have made an entire album. And it’s probably true.”

And the nights were long. “We went to another kind of world for Tusk,” Nicks said in 1979. “I think it’s fair to say that by the time we got into Tusk land, we were also collectively enjoying ourselves in various ways that the subculture offered,” says Buckingham today. “But that led to a lot of late nights. I always tried to leave by midnight or something, but a lot of times when I go out to my car, Mick [Fleetwood] would run out after me and basically grab me by the collar and pull me back in. I’d have to say I was going to the bathroom and then walk straight out to the car and drive home.” He insists that the band’s behaviour was merely a reflection of late-Seventies counterculture. “Everything just got somewhat decadent around the edges at that point.”

The direction of the album itself, though, wasn’t lost in the cocaine blizzard of its making. “I honestly don’t think it ever really affected the music that much,” Buckingham says. And in terms of drugs getting in the way of recording, he claims Tusk had nothing on 1986’s Tango in the Night. “The habits of some members of the band had gotten so bad that the making of that album was so difficult because people were just so erratic in terms of their behaviour and in terms of showing up at all.”

Everything between Stevie and me evolved in slow, slow motion and, arguably, is still doing so

Lindsey Buckingham

Still, over 10 months, nobody seemed to notice the Tusk studio bills ticking over a then record $1.4m. Not least Buckingham, whom producer Ken Caillat has described as “a maniac … into sound destruction”, twisting every knob on the console 180 degrees to see what happened and adopting push-up positions to sing into microphones taped to the floor. Buckingham has no recollection of such antics but does agree he was obsessive in the studio. “I would hope so,” he says. “If you’re leading the troops down the road you’ve got to be focused, you’ve got to be passionate.” Buckingham can, however, confirm Caillat’s story of him cutting off his own hair with nail scissors mid-session; “it was just a style statement”.

Between more traditional Rumours-style contributions from Nicks and McVie – folk country drifters like “Over & Over”, “Storms”, and the single “Sara” – Buckingham’s nine songs barge out of the record like a pack of mongrels invading Crufts. They’re often dense, hyperactive garage rock clatters drenched in fuzz guitar breaks and warped, clanking percussion. “What Makes You Think You’re the One” sounds Albini-esque a decade before its time, while “Not That Funny” virtually invents The White Stripes (“You tell Jack that!” Buckingham laughs).

Yet his inherent melodicism keeps them buoyant and as we discuss each of his tracks in turn, familiar themes emerge. A certain thumbing of the nose to the music industry, yes, but also his need to keep a keeling ship of a band sailing straight (“Walk a Thin Line”) and numerous song letters to Nicks – some a little poison pen (“Not That Funny”, “That’s Enough for Me”) but others (“Save Me a Place”) more forgiving. “That’s a reflection of the fact that we were all forging ahead emotionally with our lives,” Buckingham says, “and yet there was still, underneath all of that, a great deal of love and tenderness that we had.”

It suggests he was still processing the issues of Rumours throughout Tusk. “I think I was,” he reflects. “We didn’t have the luxury of distance, and that’s how you get closure, right? You don’t have the proper way of letting go of something because all of those things are constantly in your face. It doesn’t really die or go away or evolve out in the way that it would in a more optimum set of circumstances. Everything between Stevie and me evolved in slow, slow motion and, arguably, is still doing so.”

The title track – a crazed, lumbering carnival parade of a song, accompanied by the 112-piece USC Trojan Marching Band recorded at Dodger Stadium – was an international hit, despite being a seemingly insane choice for the album’s first single. It was chosen as a showpiece for Tusk’s uncontained, expectation-defying spirit. “Warner Brothers’ people had not come down and heard a lot of what we were doing,” Buckingham chuckles. “I always have this fantasy about us delivering a finished album and them putting it on in their Tuesday afternoon boardroom meeting and listening to the whole thing and going, ‘What the f*** was that?’”

The Tusk tour was just as head-spinning. Grand pianos were winched through the windows of hotel suites, painted pink at Nicks’s request, and a tent erected side-of-stage for the band to take drugs in mid-show.

Three years later, Fleetwood Mac reverted to type on 1982’s soft rock Mirage. “Fleetwood Mac has always been a commercial entity,” Buckingham explains. “When [Tusk] didn’t sell 16 million albums, at some point Mick said to me, ‘Well, Lindsey, we’re not doing that again.’ I was like, OK, well that means we’ve got to go back. [To] return to something that we were a few years back spontaneously, and now we’ve got to recreate it forcibly. We were not even those people any more… I wasn’t sure about that. And it was difficult. It was a bit like treading water.” Commercially, too: though Mirage returned Fleetwood Mac to the top of the US album charts, it ultimately sold a million fewer copies than Tusk.

Over more recent decades, seeing multiple generations turn up at shows before he left the band in 2018, Buckingham grew to realise that Tusk was finding an appreciative new audience. “It takes the equation of time to know whether you’ve done your job right,” he says. “I feel that it has been not just vindicated but actually revered again because of what it is and because of the reason that it came to be in the first place, which is to value the artistic outcome, not the commercial outcome, absolutely.”

He hasn’t stopped following his creative instincts since. The same sense of freedom and disregard for commercial concerns is all over his dazzling solo records. “All of that,” says Buckingham, “was because of having made an album called Tusk.”