BBC

BBCThe plight of Syrian refugees – and the pressing needs of their host countries – is being discussed by EU foreign ministers in Brussels on Monday. Millions of Syrians still live outside the country, displaced by the war. Most are in Lebanon – but anti-refugee sentiment is growing there, as BBC Arabic’s Carine Torbey reports from Beirut.

“We live in constant fear and anxiety,” says Alia. “Every evening when my son comes back home, his youngest brother hugs him – relieved that he hasn’t been arrested”.

The 43-year old lives with three of her four children in Lebanon. They fled from their home in Idlib, northern Syria, one year after war broke out in 2011.

An estimated 1.5 million Syrians live in Lebanon, out of an estimated population of just over 5.3 million, making it the country with the highest proportion of refugees in the world.

Anti-refugee sentiment in the country is not new, but it has increased significantly in the last few years, following the start of Lebanon’s economic crisis in 2019.

In April, that hostility boiled over when a figure in a major Christian party was abducted and killed – a crime police blamed on a gang made up mainly of Syrians.

Mobs of vigilantes sought retribution, with innocent Syrians beaten and humiliated on the streets.

Even before April’s violence, local authorities and self-appointed community groups evicted Syrians without legal residency from their shelters, shut businesses where they worked or pressured Lebanese not to rent them houses.

“Lebanon has offered more than it can afford to the Syrian refugees,” says North Lebanon Governor Ramzi Nohra, who has been overseeing evictions of Syrians staying illegally in dwellings or compounds. “You can host a neighbour for a day or two but not forever.”

Mr Nohra denies being anti-refugee, and says he’s just implementing the law.

“Would any country accept that you overstay your visa? We welcome Syrians who have the right documents, and our actions are only against those who are staying illegally in the country”.

According to the UN refugee agency, the UNHCR, 80% of Syrians don’t have legal residency, which means they could be arrested and deported at any moment.

It also says nine out of 10 are living in extreme poverty, however many Lebanese believe Syrians in the country are propped up by aid provided by the UNHCR and its partners. Some even think they benefit directly from it.

“I started overhearing people at places like the supermarket or the street saying: Look at the Syrians. They are living the good life while we can’t afford anything in our own country”, says Alia. “If only they knew what kind of life we live”.

EU commissioner Ursula Von Der Leyen visited Lebanon on May 2, to announce a one-billion-euro aid package to the country.

This was widely seen in Lebanon as a bribe to keep the Syrian refugees on its soil, by cracking down on illegal immigration towards Europe.

Days afterwards, Lebanon’s parliament issued a recommendation to the government urging it to take all measures to deal with Syrians who are in the country illegally.

It was the first time that a political consensus emerged over this issue.

The official position of Lebanon is that large swathes of Syria have become safe for the refugees to return to and that the UN agencies should encourage this return by providing aid inside Syria, rather than encouraging them to stay away from their country by giving them aid in Lebanon.

MPs set a one-year deadline for the government to ensure “the return of the Syrians who have entered and reside illegally in Lebanon to their country”.

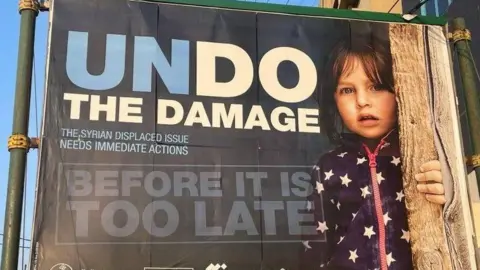

Across many parts of Lebanon, billboards have emerged showing a picture of what appears to be a refugee child with the message: “UNDO the damage”.

The person behind the campaign – a Lebanese art director – confirmed to the BBC that it was a personal initiative.

He felt he needed to do something about the “refugee crisis”, seen by many Lebanese as posing an existential threat to the country.

But regardless of who funds this campaign, its message echoes what has become a widespread narrative in the country – refugees are seen as “damaging” and the UN is partly responsible.

Contacted by the BBC, the UNHCR in Lebanon said: “There is no international conspiracy to keep Syrian refugees in Lebanon and there is no hidden agenda on this.

“We have always been very transparent on our position: The United Nations, including UNHCR, does not hinder the return of refugees to Syria.”

But some refugees have already decided to seek a life elsewhere. Cyprus, just a few hundred kilometres away across the Mediterranean Sea, has seen a 27-fold increase in the number of Syrian refugees coming from Lebanon, according to its ministry of interior.

Around a month ago, Alia and her children were among 35 people on a boat to the island, hoping to join her husband and fourth child who made the same illegal journey a year ago.

They made it to Cypriot waters but the coastguard forced their boat to return.

Despite all the risks that this trip entailed, Alia says she wasn’t afraid to take it, believing her children have no future in Lebanon.

“What could have happened?” she says. “We could have died. I am dead either way, here or there”.