Maya Meshel / BBC

Maya Meshel / BBCA few metres from a charred home in Kibbutz Be’eri, Simon King tends to a patch of ground in the sunshine. The streets around him are eerily quiet, the silence punctuated only by the sound of air strikes that ring in the near distance.

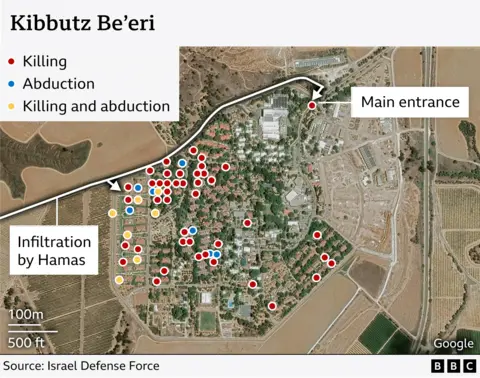

In this community almost a year ago, 101 people were killed after gunmen from Hamas and other groups rampaged through Be’eri’s tree-lined streets, burning homes and shooting people indiscriminately. Another 30 residents and their family members were taken to Gaza as hostages.

Survivors hid in safe rooms all day and long into the night – exchanging horrifying details with each other over community WhatsApp groups, as they tried to make sense of what was happening.

Reuters

ReutersThe kibbutz was a strong community, where people lived and operated together as one. Neighbours were more like extended family. It is one of a small number of kibbutzim in Israel that still operates as a collective.

But now, post-7 October, the collective is splintered – psychologically and physically.

About one in 10 were killed. Only a few of the survivors have returned to their homes. Some travel back to the kibbutz daily to work, but can’t face overnight stays. Many, after months in a hotel, are now living in prefabricated buildings on another kibbutz 40km (25 miles) away.

The community, built up over nearly 80 years, is being tested like never before, and its future is uncertain.

There are reminders everywhere of those who didn’t survive – says Dafna Gerstner, who grew up in Be’eri, and spent 19 terrifying hours on 7 October holed up in a safe room – designed to protect residents from rocket attacks.

“You look to the left and it’s like, ‘Oh it’s my friend who lost her parents.’ You look to the right, ‘It’s my friend who lost her father,’ [and then] ‘She lost her mother.’ It’s everywhere you look.”

Inside Be’eri, surrounded by a high fence topped with barbed wire, you are never far from a house completely burnt or destroyed, or an empty patch of land where a home, wrecked that day, has been demolished.

Some streets might, upon first glance, appear almost untouched – but look closely and even there you will see markings spray-painted on walls by military units on or after 7 October. Houses where people were killed or kidnapped have black banners on the facades with their names and photos.

In the carcass of one burnt-out home, a board game rests on top of a coffee table, next to a melted television remote control. Food, long-rotten, is still in the fridge-freezer and the smell of burning lingers.

“Time stood still in the house,” says Dafna, 40, as she pokes through the ash-covered wreckage. She and her family had been playing that board game on the eve of the attacks.

Here, her disabled father and his Filipina carer hid for hours in their fortified safe room, as their home burned down around them. Dafna says it is a miracle they both survived.

Her brother did not. A member of Be’eri’s emergency response squad, he was killed in a gunfight at the kibbutz’s dental clinic. Dafna was staying in his house at the time, on a visit from her home in Germany.

Dozens of buildings in Be’eri are spattered with bullet holes – including the nursery. The play park and petting zoo are empty. No children have moved back, and the animals have been sent to new homes.

The kibbutz’s empty streets sometimes come alive, though, in a surprising way – with organised tours for visitors, who give donations.

Israeli soldiers, and some civilians from Israel and abroad, come to see the broken homes, and hear accounts of the devastation, in order to understand what happened.

Two of those who volunteer to lead the tours, Rami Gold and Simon King, say they are determined to ensure what happened here is remembered.

Simon, 60, admits this can be a difficult process.

“There’s a lot of mixed feelings and [the visitors] don’t really know what to ask but they can see and hear and smell… it’s a very heavy emotional experience.”

Rami, 70, says these occasions are often followed by restless nights. Each tour, he says, takes him back to 7 October.

He is one of the few who moved back to Be’eri after the attacks.

Maya Meshel / BBC

Maya Meshel / BBCAnd the tours are not popular with everyone. “At some point it felt like someone took over the kibbutz – everybody was there,” Dafna says.

But Simon says the stories have to be told. “Some don’t like it because it’s their home and you don’t want people rummaging around,” he says. “But you have to send the message out, otherwise it will be forgotten.”

At the same time, both he and Rami say they are looking to the future, describing themselves as “irresponsible optimists”. They continue to water the lawns and fix fences, amid the destruction, as others build new homes that will replace those destroyed.

Simon describes the rebuilding as therapy.

Established in 1946, Be’eri is one of 11 Jewish communities in this region set up before the creation of the state of Israel. It was known for its left-leaning views, and many of its residents believed in, and advocated for, peace with the Palestinians.

After the attacks, many residents were moved into a hotel by the Dead Sea – the David Hotel – some 90 minutes’ drive away.

In the aftermath of the attacks, I witnessed their trauma.

Shell-shocked residents gathered in the lobby and other communal areas, as they tried to make sense of what had happened, and who they had lost, in hushed conversations. Some children clung to their parents as they spoke.

Still now, they say, the conversations have not moved on.

“Every person I speak to from Be’eri – it always goes back to this day. Every conversation is going back to dealing with it and the effects after it. We are always talking about it again and again and again,” says Shir Guttentag.

Like her friend Dafna, Shir was holed up that day in her safe room, attempting to reassure terrified neighbours on the WhatsApp group as Hamas gunmen stormed through the kibbutz, shooting residents and setting homes on fire.

Shir twice dismantled the barricade of furniture she had made against her front door to let neighbours in to hide. She told her children, “it’s OK, it’s going to be OK” as they waited to be rescued.

When they were eventually escorted to safety, she looked down at the ground, not wanting to see the remains of her community.

In the coming months at the Dead Sea hotel, Shir says she struggled as people began to leave – some to homes elsewhere in the country or to stay with families, others seeking to escape their memories by heading abroad.

Each departure was like “another break-up, another goodbye”, she says.

It is no longer unusual to see someone who is crying or looking sad among Be’eri’s grieving residents.

“In normal days it would have been like, ‘What happened? Are you OK?’ Nowadays everyone can cry and no-one asks him why,” Shir says.

Shir and her daughters, along with hundreds of other Be’eri survivors, have now moved to new, identical prefabricated homes, paid for by the Israeli government, on an expanse of barren land at another kibbutz, Hatzerim – about 40-minutes drive from Be’eri.

I was there on moving day.

It feels a world away from the manicured lawns of Be’eri, though grass has now been planted around the neighbourhood.

When single mother Shir led her daughters, aged nine and six, into their new bungalow, she told me her stomach was turning from excitement and nerves.

She checked the door to the safe room, where her children will sleep every night, noting that it felt heavier than the door at Be’eri. “I don’t know if it’s bulletproof. I hope so,” she said.

She chose not to bring many items from Be’eri because she wants to keep her home there as it was – and to remind herself that she will one day return.

Handout

HandoutThe mass move to Hatzerim happened after it was put to a community vote – as is the case with all major kibbutz decisions. It is estimated about 70% of Be’eri’s survivors will live there for the time being. About half of the kibbutz’s residents have moved in so far, but more homes are on the way.

The journey from Hatzerim to Be’eri is shorter than it was from the hotel – and many people make the trip every day, to work in one of the kibbutz’s businesses, as they did before.

Shir travels to Be’eri to work at its veterinary clinic, but can’t imagine returning to live there yet.

“I don’t know what needs to happen, but something drastic, so I can feel safe again.”

Maya Meshel / BBC

Maya Meshel / BBCIn the middle of the day, the Be’eri lunch hall fills with people as they gather to eat together.

Shir, like many others, has reluctantly applied for a gun licence, never wanting to be caught off-guard again.

“It’s for my daughters and myself because, on the day, I didn’t have anything,” she says.

Her mother’s long-term partner was killed that day. When they talk about it, her mother says: “They destroyed us.”

Reuters

ReutersResidents say they have relied on the support of their neighbours over the past year, but individual trauma has also tested a community that has historically operated as a collective.

The slogan at Be’eri is adapted from Karl Marx: “Everyone gives as much as he can and everyone gets as much as he needs.” But these words have now become hard to live by.

Many residents of working age are employed by Be’eri’s successful printing house, and other smaller kibbutz businesses. Profits are pooled and people receive housing and other amenities based on their individual circumstances.

However, the decision of some people not to return to work has undermined this principle of communal labour and living.

And if some residents decide they can never return to Be’eri that could, in turn, create fresh problems.

Many have little experience of non-communal living and would struggle financially if they lived independently.

The 7 October attack has also quietened calls for peace.

The kibbutz used to have a fund to help Gazans who crossed the border daily to work on-site there. Some residents would also help arrange medical treatment for Gazans at Israeli hospitals, members say.

Now, among some, strong views to the contrary are shared in person and on social media.

“They’ll [Gazans] never accept our being here. It’s either us or them,” says Rami.

Several people bring up the killing of resident Vivian Silver – one of Israel’s best-known peace advocates.

“For now, people are very mad,” Shir says.

“People still want to live in peace, but for now, I can’t see any partner on the other side.

“I don’t like to think in terms of hate and anger, it’s not who I am, but I can’t disconnect from what happened that day.”

Shir wears a necklace engraved with a portrait of her lifelong friend Carmel Gat, who was taken hostage from Be’eri that day.

Her biggest dream was that they would be reunited – but, on 1 September, Carmel’s body was found alongside five other hostages.

The IDF said they had been killed by Hamas just hours before a planned rescue attempt. Hamas said the hostages were killed in air strikes – but an autopsy on the returned bodies concluded they had all been shot multiple times at close range.

Be’eri is still waiting and hoping for the return of others. So far, 18 have been brought back alive, along with two dead bodies, while 10 are still in Gaza, at least three of whom are believed to still be alive.

Behind Dafna’s father’s house, 37-year-old Yuval Haran stands in front of the home where his father was killed, and many relatives were taken hostage, on 7 October. His brother-in-law Tal is still being held in Gaza.

“Until he comes back, my clock is still on 7 October. I don’t want revenge, I just want my family back, I just want to have a quiet peaceful life again,” Yuval says.

In all, some 1,200 people were killed across southern Israel on 7 October, with 251 taken to Gaza as hostages. Since then, in the Israeli military operation in Gaza, more than 41,000 people have been killed according to the Hamas-run health ministry.

Hundreds of people – combatants and civilians – have also been killed in Lebanon in Israeli air strikes against the armed group Hezbollah, in a significant escalation of their long-running conflict.

Residents from Be’eri say that before 7 October, despite their proximity to the Gaza fence, they always felt safe – such was their faith in the Israeli military system. But that faith has now been shaken.

“I’m less confident and I’m less trusting,” Shir says.

She relives the events in her dreams, she says.

“I wake up and I remind myself it’s over. But the trauma is, I think, for life. I don’t know if I can ever feel fully safe again.”

This summer Rami and Simon also took on the sombre task of digging graves for Be’eri’s dead, who are only just being moved back to the kibbutz from cemeteries elsewhere in Israel.

Maya Meshel / BBC

Maya Meshel / BBC“After the 7th [October] this area was a military zone, we couldn’t bury them here,” says Rami, as he looks over the graves, a rifle slung across his body.

Simon says it brings up strong and passionate feelings – “but in the end they’re back at home”.

Each time a person is returned, the kibbutz holds a second funeral, with many residents in attendance.

Shir, in the temporary site at Hatzerim, says that for now, she is drawing strength from the community around her.

“We’re not whole, but we will be I hope,” she says.

“It’s a grieving community – sadder and angrier – but still a strong community.”