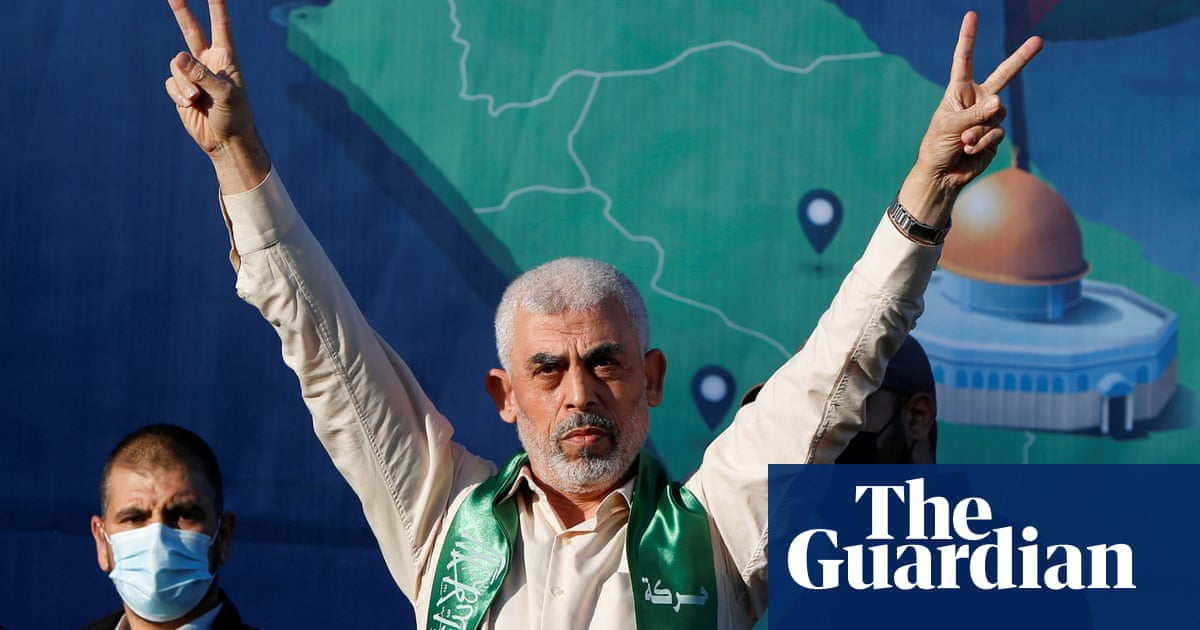

In the end, after a year-long, multi-agency manhunt involving the latest technology, Israel’s best special forces and American assistance, Yahya Sinwar appears to have been killed by regular soldiers who had stumbled into him and had no idea whom they had killed.

According to the initial reports, they were not there on an assassination operation and had no prior intelligence that they could be in the vicinity of the elusive Hamas leader, architect of the 7 October attacks, the man Israel most wanted to kill. It was only after they took a closer look at his face and found identity documents on him that the troops realised they had got Sinwar.

Along the way, Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have smashed much of Gaza and are estimated to have killed more than 42,000 Palestinians, driving two million from their homes, a humanitarian disaster Sinwar set in motion with the sheer brutality of the initial surprise assault a year ago, killing 1,200 Israelis and taking 250 hostage.

Sinwar’s last reported sighting had been just a few days after the 7 October attack, when he appeared out of the subterranean gloom in a Gaza tunnel when a group of hostages were been held.

In fluent Hebrew, perfected over more than 22 years in an Israeli prison, Sinwar reassured them that they were safe and would soon be exchanged for Palestinian prisoners. One of the hostages, Yocheved Lifshitz, an 85-year-old veteran peace campaigner from the Nir Oz kibbutz, had no time for his show of concern for their welfare and challenged the Hamas leader to his face.

“I asked him how he wasn’t ashamed to do something like this to people who had supported peace all these years?” Lifshitz told the Davar newspaper after her release following 16 days in captivity. “He didn’t answer. He was quiet.”

A video recorded on Hamas security cameras at about the same time, on 10 October, and found by the Israeli military some months later, shows Sinwar following his wife and three children through a narrow tunnel and disappearing into the murk.

The ferocious manhunt that ensued involved a mix of advanced technology and brute force, as his pursuers have shown themselves prepared to go to any lengths, including causing extremely high civilian casualties, to kill the Hamas leader and destroy the tight circle around him.

The hunters were a taskforce of intelligence officers, special operation units from the IDF, military engineers and surveillance experts under the umbrella of the Israeli Security Agency, more widely known by its Hebrew initials, or by the acronyms Shabak or Shin Bet.

Personally and institutionally, this team was seeking redemption for the security failures that allowed the 7 October assault to happen. But despite their motivation, they faced more than a year of frustration.

“If you’d told me when the war began he would still be alive [a year later], I would have found it amazing,” said Michael Milshtein, a former head of the Palestinian affairs section in Israeli Military Intelligence (Aman). “But remember, Sinwar prepared for a decade for this offensive and IDF intelligence was very surprised by the size and length of the tunnels under Gaza and how sophisticated they were.”

Some in the Israeli defence establishment believed that Sinwar would be surrounded by hostages as human shields, though others maintained that would slow him down and make his entourage a bigger target. Certainly the risk of killing hostages did not stop the IDF dropping 2,000lb bombs on suspected Hamas leadership targets. In the end, the Israelis reported finding no sign of hostages in the vicinity of Sinwar when he was killed, who seems to have been in the company of just two other men.

There was no shortage of expertise among Sinwar’s pursuers. Targeted killings have been a core tactic of Israel’s military since the founding of the state. Since the second world war, Israel has assassinated more people than any other country in the western world.

Yahalom, a special section within the Combat Engineering Corps, has more experience in tunnel warfare than any of its counterparts in western armies, and has access to state-of-the-art US-made ground-penetrating radar. The clandestine signals intelligence unit 8200 is a global leader in electronic warfare and has been eavesdropping on Hamas communications for decades.

The Shin Bet lost many of its sources in Gaza after Israel pulled out of the territory in 2005, but worked hard to rebuild its network of informants after Israel launched its ground invasion last October, recruiting from among the desperate flows of Palestinians fleeing the onslaught.

Despite the capabilities of this formidable taskforce, it came close to catching Sinwar just once before Thursday’s fatal encounter, in a bunker beneath his home town of Khan Younis in late January. The fugitive warlord had left behind clothing and more than 1m shekels (over £200,000) in wads of banknotes. This was seen by some as a sign of panic, though the Hamas leader was ultimately estimated to have left a few days before Israeli forces raided the bunker.

The assumption made by Sinwar’s trackers was that he had abandoned using electronic communication, well aware of the skills and technology possessed by his hunters. It was not only Hebrew that Sinwar studied in Israeli jail but also the habits and culture of his enemy.

“He really understands the basic instincts and the deepest feelings of Israeli society,” said Milshtein, now at the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel Aviv University. “I’m quite sure every move he makes is based on his understanding of Israel.”

Throughout his year in hiding, Sinwar continued to communicate with the outside world, albeit with apparent difficulty. The long, fruitless negotiations over a ceasefire in Cairo and Doha were frequently paused while messages were sent to and from the subterranean commander. The dominant theory was that Sinwar uses couriers to remain in command, drawn from a small and shrinking coterie of aides he trusts, starting with his brother Mohammed, a senior military commander in Gaza.

The team hunting Sinwar hoped that his need for contact with couriers, to issue orders and control the hostage negotiations, would ultimately prove his undoing, just as a courier led American trackers over several years to Osama bin Laden’s hideout in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

It is believed that it was a courier who led the Israeli hunters to their biggest scalp of the war before Sinwar. At 10.30am on 13 July, Mohammed Deif, Hamas’s veteran commander who had topped Israel’s most wanted list since 1995, emerged from a hiding place near a camp for displaced people at al-Mawasi to take in some air with a close lieutenant, Rafa’a Salameh. Within an instant, both men were killed by bombs dropped by Israeli jet fighters – at least, according to IDF accounts – along with scores of Palestinians. Hamas insists that Deif is still alive but he has not been seen since.

Many in the Israeli security establishment rued what they saw as a missed historic opportunity in September 2003 when they had planes ready to bomb a house where the entire Hamas leadership was holding a meeting. After furious argument in the military chain of command, the air force used a precision missile fired into the presumed meeting room rather than flattening the whole building with a hail of bombs, out of concern for civilian casualties. They picked the wrong room and the Hamas leaders survived.

By July this year, the likelihood of killing large numbers of civilians was no longer an obstacle. In targeting Deif, the air force used 2,000lb bombs, the very weapons the Biden administration had stopped sending in May because of their indiscriminate destructive force. Israel reportedly dropped eight of them on 13 July. Ninety Palestinians in the vicinity were killed and nearly 300 injured.

Yossi Melman, a co-author of Spies Against Armageddon and author of other books on Israeli intelligence, said Deif may have made a mistake that Sinwar had avoided.

“Deif was maybe more arrogant or maybe he told himself they tried to kill me so many times, and I lost an eye and an arm but I still survived, so maybe God is with me,” Melman said. “The Shabak and the army were waiting just for this opportunity. All these targeted killings are about waiting for the one minor mistake by the other side.”

There was some talk over the negotiating tables in Cairo and Doha of the past year of cutting a deal in which Sinwar went into exile, and some suggested that he could have crossed the border, hiding in a tunnel on the Egyptian side of the town Rafah. Such theories underestimated the ideological zeal of a man who rose through Hamas ranks as the executioner of suspected informers.

Milshtein, whose job in the Aman military intelligence service was to study Sinwar and other Hamas leaders, predicted months before his eventual death: “It is in his basic DNA to stay in Gaza and to fight until death. He will prefer to die in his bunker.”

In that case, Sinwar got his wish. His death was perhaps preordained by the sheer determination of both sides. He would never leave or surrender, and if the hi-tech intelligence-led hunt for him failed, Israel preferred to flatten Gaza until he was finally killed.

Whether his death will stop the war is another question.

Ram Ben-Barak, a former deputy director of the Mossad, had predicted that after Sinwar’s fall “someone else will come”.

“It is an ideological war, not a war about Sinwar,” Ben-Barak said.

Milshtein said: “After almost 50 years of assassinations, we understand this is a basic part of the game. Sometimes it is necessary to assassinate a very prominent leader. But when you start to think it will be a gamechanger and that an ideological organisation will collapse because you kill one of its leaders, that is a total mistake.

“You cannot create a fantasy. It will not end the war.”