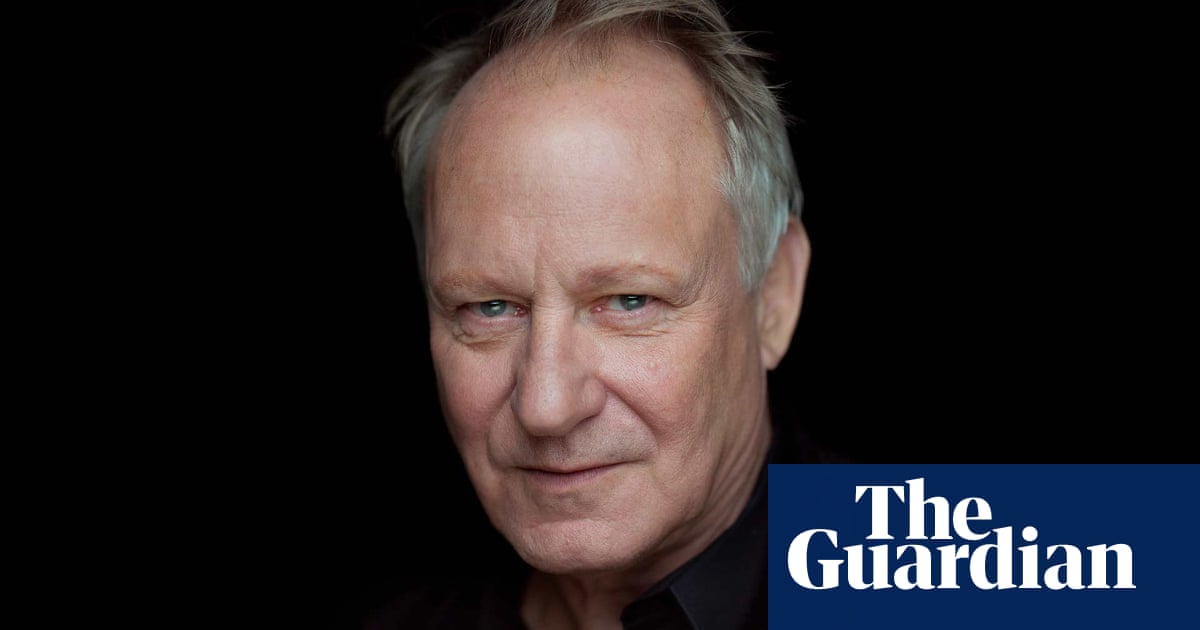

Stellan Skarsgård is speaking to me from his cabin, outside Stockholm, and why shouldn’t he look relaxed and happy, in those clement, sun-dappled surrounds? But it is so disconcerting. His performance in What Remains, as a battle-scarred police officer, trying to keep hold of his family, his bearings and his scepticism in the face of a criminological modernity that puzzles him, joins a body of knotty work that UK audiences would probably date back to Breaking the Waves, Lars von Trier’s 1996 classic. His smallest facial gesture speaks fathomless emotion. I am a huge Mamma Mia! fan – in which he plays Bill Anderson – so I have seen Skarsgård smile, but even then, not all the time.

What Remains is based, loosely, on a famous case in Sweden: it was the 90s, and the so-called “retrieved memory” technique was huge, even though in the US, where it was developed, it had already been disallowed as reliable evidence. “All psychologists in Sweden were using retrieved memory at the same time, a lot of men were put in jail for violating their children,” Skarsgård says. “It’s really the fabrication of memory. It was very optimistic, to think you can just open up the memory and look at it. Every divorce you’ve been through, you’ll know, the truth isn’t exactly as everybody says.”

This came to a head in the 90s, with the case of Mads Lake, the long-term resident of a psychiatric hospital, who has definitely been abused as a child and has himself “committed offences against children, we don’t know if he’s raped one, but it’s a terrible mess”, says Skarsgård. Told in austere but beautiful landscapes, bleak Formica interiors, freighted pauses and this small cast, chasing one another towards an impossible certainty, the film is exquisitely disorienting. A folie à deux between Mads and the psychologist Anna Rudebeck (played with quiet intensity by Andrea Riseborough) led Lake, Rudebeck and Skarsgård’s policeman, Soren Rank, to near certainty that Lake was, in fact, Sweden’s first serial killer.

Lake is played by Skarsgård’s son Gustaf, one of four acting sons including Alexander and Bill (Stellan has eight children in total). Gustaf shares the Skarsgård magnetism but is emphatically not playing this for charisma: greasy, furtive and confused, his distress comes powerfully off the screen.

“I’m full of happiness watching him work,” Skarsgård says of his son, “because he’s so good. I don’t see him suffering, I know he enjoys it. We’re actors, for fuck’s sake.” The family is very close: “There’s a certain competition between my sons, but not in the sense that they don’t appreciate each other’s success or have any grudge against each other.” They all live within five minutes of each other in Stockholm, like Swedish arthouse Waltons. It wasn’t deliberate, he says, raising so many actors. “I didn’t care what they became when they grew up, they could do anything. But obviously they saw that I had fun doing the acting stuff, so they became actors. They’re all very different. I am amazed how different they can be from each other, having the same parents. Well, some of them have the same parents.”

What Remains was written by Everett-Skarsgård, and she and the director, Ran Huang, had Gustaf in mind before they cast Stellan. “I couldn’t not be involved, because it was in my home. My wife was writing it and she was tearing her hair out all the time. I don’t usually mix my private life with my professional life. You can get very tied up, and eventually it starts conflicts that you can’t handle. But I couldn’t say no to working with that dark material, and with Gustaf.”

If the case gripped Sweden in the 90s, it was partly because the country had never had a serial killer, which will come as news to fans of Scandi noir. The main thing I know about the land block, from its cultural exports, is how incredibly good, and experienced, its fictional detectives are, particularly at finding serial killers. “And we don’t have one! We still haven’t had a serial killer. So we don’t know what it is,” Skarsgård says.

“The Scandi noir thing is pretty silly, I must say,” he adds. “I did one of the first Scandi noir films, Insomnia – it didn’t have that label at the time. Marketers, they want to label everything.” While he has done a number of crime stories, he says: “This is only my second policeman. The first one was in River. I don’t like police series, but Abi Morgan had written such a beautiful script, it was not about police work, it was about human beings. And I also said: I can’t say the police lines. You’ve got to have someone else say them.” Wait, what? “You know, ‘Download the CCTV’, ‘Check his bank accounts’, all that stuff. I can’t say things like that without laughing.”

In real life, Sweden is a low-crime nation of peace lovers, or at least, it was. “It is changing, that’s the sad thing,” he says. “We used to be seen as a very wealthy country with very happy people. And, of course, a neutral country. But now we’re a member of Nato, we have doubled our arms budget. Like all of Europe. Everybody’s screaming to kill, kill, kill.” He continues: “Everybody is so excited now, by war. They’re showing the prime minister of Denmark and the prime minister of Sweden, and they’re sitting in fighting planes, and they’re showing off the latest submarine, and their pride in the Swedish rocket gun. There’s a pride in weapons that we were once ashamed of before.”

If this feels like a swerve, from the dark and contemplative What Remains, to Nato and the perils of the future, it’s not surprising to Skarsgård, for whom it is obvious that art should be “the place for refugees, the dropouts, the insane people, the homosexuals. We have to defend our outsider values.”

That has been a constant thread in Skarsgård’s career, risk-taking and rebellion, which he ventriloquises through Von Trier, and Breaking the Waves. “I felt that Lars was a very radical man. He said, I know what films I’m making now. I’m making the films that haven’t been made. I felt excited. It was dangerous and shocking in so many ways. And you didn’t think you could make films like that any more. Or, ever. He is truly original, he can’t do anything normal.”

But you wouldn’t call Skarsgård an intellectual purist – there’s plenty of Pirates of the Caribbean in his long career, as well as Marvel films and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo – and he insists on the profundity of having a laugh, as was the case on Mamma Mia!. “As soon as I gave up any ambition for my singing and dancing, I realised the story: the quality was not the story; the script was not the story; it was that you saw a lot of actors having fun together, and it was very contagious.”

“As an actor,” Skarsgård says, “you’re don’t create your own art, you’re a reproductive artist, in a way. But I feel very zen about it. I’ve not been too pretentious about my arthouse films. I enjoy them, I think they’re delicious. I’m approaching my death now,” he says, cheerfully. “There’s a limit to the number of roles I’ll get, limited time. I want to continue doing what I’ve done, making the things that haven’t been made.”