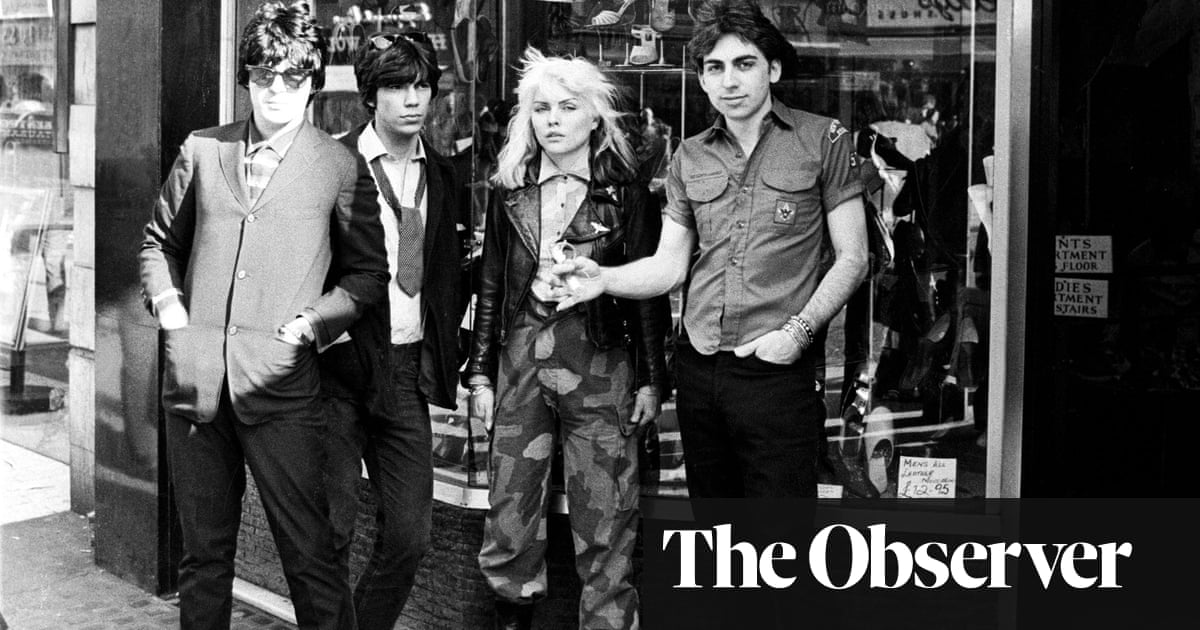

In the late 1970s, in downtown Manhattan, the musician Chris Stein became friendly with a young artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat. Both men were a long way from the celebrated cultural figures they would become: Stein had just started to make some money as the guitarist of New York new-wave act Blondie, the band he co-founded with singer Debbie Harry in 1974; the teenage Basquiat, unable to pay for canvases, painted graffiti on to walls, floors or any material he could lay his hands on.

“I knew Jean pretty well and I said, ‘Do a painting’,” Stein recalls now on a video call from his apartment in New York. “I’m fairly certain it was the first thing he ever did on a canvas, because he had been painting on cardboard. He knew I was interested in militaria, so it was army men fighting with little cannons and shooting. It was pretty monochromatic and it was on a big piece of burlap, a rough canvas, not stretched on a frame, just by itself. And he gave it to me for 200 bucks. Then I later heard that he had been telling people how much he’d ripped me off for 200 bucks.”

A few years later, though, before Basquiat died of a drug overdose in 1988 aged 27, Stein found himself short of funds. He sold the painting for $10,000 to Diego Cortez, an art curator and co-founder of the Mudd Club, where Stein and Basquiat would hang out. I point out – probably unhelpfully – that this figure is a fraction of what it would have been worth had Stein hung on to it: the record for a Basquiat painting is Untitled from 1982, which sold for $110.5m in 2017.

“Of course, sure,” replies Stein, now 74, with a wry smile. “No, I wish I’d gotten more of his work. Same with Andy [Warhol], but that’s just how it is. I could have bought all his fucking Marilyns and Elvises and things like that, but I just saw it all the time, so it was like, ‘OK…’”

Stein, who has thick, platinum hair that is centre-parted in neat curtains and a tidy goatee, is full of such stories: a lifelong New Yorker, his second home for much of the 1970s seems to have been CBGB, the infamous East Village music venue that was the centre of the punk and new-wave scenes. His companions back then may have been the Ramones, William Burroughs, Lou Reed or David Bowie. Or, of course, Harry, who was Stein’s romantic partner for more than a decade until the mid-80s and has now been a friend for half a century. When, during the Covid lockdowns, Stein started work on his memoir, his concern was that readers wouldn’t believe all the “weird-ass” stories had actually happened. “There’s a lot of odd stuff in it,” says Stein of the book, Under a Rock, which is published this week. “The big challenge for me was just making all these hundreds, thousands of little anecdotes have a flow.”

There certainly are some crackers. Like the time in 1977 when Iggy Pop asked Blondie to open the 20 or so dates of his US tour. Bizarrely, Bowie had signed on to play keyboards in Iggy’s band (while also travelling between performances in a limousine) and one day when he was alone with Harry he asked her: “Can I fuck you?” Harry, straight-faced, shot back: “I don’t know, can you?” Iggy also showed some interest, but Harry rebuffed him, too.

Did Stein mind? “Nooooo,” he says. “Debbie told me about it at that time and it was just… I think they felt obligated. And I don’t know how much Iggy hit on her because he had a girlfriend with him on the tour. So I’d have to ask her about that, but Bowie certainly did.”

Perhaps the most surprising element of Under a Rock, though, is how clear-eyed and unromantic Stein is about New York in the 70s and 80s. The city may have been a creative hotbed in those decades, but day-to-day, it could feel like living in a car crash. Stein was in thrall to drugs in that period – first pot, then cocaine and heroin – and while he came out the other side, many of his close friends, such as Basquiat, did not. Crime was out of control: Stein was repeatedly robbed and burgled; in one harrowing scene, he describes how a man forced him and Harry into their apartment at knife-point, tied them up in different rooms and raped Harry. “All these years later and I still want to kill this person; not a good feeling,” writes Stein.

“It was a dangerous environment,” he says. “We got attacked, all this stuff was going on for everybody. It wasn’t going on uptown for the rich people so much, but we were just all living on the fringes of society down there, so it was a different situation.

“Everybody I knew in New York at one point or another said how terrible it was and they wanted to leave,” Stein continues. “But nobody left. It was just part of the zeitgeist of the times: being miserable and put upon by the environment, which was very grim. Where we lived on the Bowery [on Manhattan’s Lower East Side]… ahhh, you pass by now and there’s a giant fucking Whole Foods across the street and the New Museum, which is this very fancy corporate art endeavour. It just makes me laugh, because it’s so at odds. It’s mind-boggling, all that.”

Stein grew up across the East River, in postwar Brooklyn. His parents, Ben, a Russian émigré, and Stel, who had Armenian-Romanian heritage, met at a gathering of the Communist party in New York, but Stein admits this probably sounds “more glamorous and/or terrible” than it was. He was a daydreamer as a child and, after his father’s death when he was 13 and some early LSD trips, he began to experience hallucinations and psychotic episodes in his late teens. He spent some weeks in institutions and, with the help of medication, the delusions diminished.

Music was always all-consuming: during one mental-health low, he became obsessed with the idea that the White Album by the Beatles was a live record and the band had to recreate it every time someone played the LP on their stereo. Another seminal artist for Stein in the late 60s was Dr John, whose music combined voodoo rhythms with New Orleans blues, jazz and funk. On a visit to the UK in the early 70s, he stumbled on to the Notting Hill carnival and had his first proper exposure to reggae. “I just had really diverse musical tastes,” says Stein. “I was always looking for new forms and trying to pull disparate elements into the music.”

These magpie tendencies would eventually find an outlet with Blondie. Stein had not long graduated from New York’s School of Visual Arts and was playing guitar in different bands when, in 1973, he went to a gig at the Bobern Tavern by all-girl trio the Stilettos. Harry was a brunette who worked in a hair salon in New Jersey back then. “She was super-charismatic even at that very early stage,” Stein remembers. “I suppose I saw what people saw later on, just very early. And she was just so fucking cute. So fucking cute: it was crazy! And on top of that, being a great singer, so it was probably a little bit of all of it.”

Harry, who contributes the foreword to Under a Rock, puts it this way: “A few weeks later we needed a bass player and Chris and I started what became a very long music and love relationship.”

Soon afterwards, Harry, bored at work, cut her hair short and dyed it: Blondie was born. “I remember when she came home with the Twiggy haircut,” says Stein. “And some time after that, she just announced that somebody had leaned out of a truck and yelled, ‘Hey, blondie!’ at her and that inspired the whole thing. We had been seeking a name and that seemed to suddenly embody it.”

Success was far from ordained for Blondie, which consisted of Harry, Stein and a turbulent lineup of three or four others, sometimes known generically as “the guys”. Their first two albums built a small following, more in the UK than the US. But it was only with the release of their third record, Parallel Lines, in 1978, which combined powerpop, new wave and disco, that the band left the underground for the mainstream. Featuring the classic tracks Hanging on the Telephone, One Way Or Another and the global hit Heart of Glass, it was the bestselling album in the UK in 1979 and went on to shift more than 20m copies worldwide.

“I don’t know if anybody really expected anything,” says Stein, of Blondie’s breakthrough in the 1970s. “The New York Dolls, who were a model for many of us on the downtown scene, went out into America and were not successful. And it was several years before there was any attention from the outside. Some of the first attention we got at CBGB was from the British music press, Melody Maker and those guys coming over, very early on before we got any national American press.”

after newsletter promotion

The next few years were a blur, especially to Stein, whose drug use was getting out of hand. There were more high points: not least the singles Atomic, Call Me and Rapture, written by Harry and Stein, which became the first song featuring rapping to reach No 1 in the US (Basquiat has a cameo in the video, recruited after Grandmaster Flash failed to turn up). But, with the record label expecting at least an album a year, and having to support it with touring, tensions erupted in the band and, in November 1982, they disbanded. “It was hard to keep up,” says Stein. “That’s why everybody self-imploded after a while in the early 80s. It was tremendous amounts of pressure. And just our own weaknesses, and all the drug abuse. For me, anyway.”

It was also becoming clear that Stein was ill. He had blisters all over his back and legs: he feared it might be Aids but, in 1983, he was diagnosed with pemphigus, an autoimmune disease that was eventually brought under control with steroids. Harry looked after Stein, but their relationship came under strain as they both went through rehab for drug addiction. “Debbie and I had grown out of sync,” he writes in Under a Rock. “Maybe in part because of her going off methadone and me staying on it, maybe lots of stuff, but things ran their course and she moved out.”

The band and his relationship had broken up – was it a chaotic time for Stein? “I am always like the boy who stood on the burning deck,” he says, referencing the 1826 poem Casabianca by Felicia Dorothea Hemans. “I’m a fan of chaos, I like it. But I guess, inevitably, there’s parts of you that get befuddled by too much chaos. I think it took its toll, but it’s not something I’m against.”

Stein is assiduous not to glamorise drug use, either in conversation or the book. In 1999, he married the actor Barbara Sicuranza and they had two daughters, Akira and Vali. Last year, Stein announced that Akira, aged 19, had died from an accidental overdose. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever dealt with, and am dealing with,” he writes in Under a Rock. “I thought that I presented my own drug experiences in a negative light to our kids, but I’m racked with guilt that any discussions might have been misconstrued.”

Since Akira’s death, Stein has wondered if it is possible to change one’s own path. In his memoir, he references the 1915 novel Strange Life of Ivan Osokin by Russian author PD Ouspensky, in which a magician gives Ivan the chance to correct the mistakes from his past (the idea would later inspire the film Groundhog Day). But despite the fresh start, Ivan is doomed to repeat his actions again and again, and Stein goes along with that. “I don’t know if it would have been easy to do anything differently,” he says.

Blondie reformed in 1997 and came back strongly: their single Maria went to No 1 in the UK, giving the band the distinction (alongside Michael Jackson) of having topped the charts in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. They were inducted to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006. Their last album was the well-regarded Pollinator in 2017, but Stein reveals that Blondie has recently finished a new record, which could be released this year. “It’s good,” he says, “a little experimental in places.”

Stein no longer plays live with the band, and is not sure he will again. “After 50 years and all my health issues, I live a little more sedentary now,” he says. “Just doing the hotels and the airplanes is hard. And I’ve got a fucking heart condition and I’m at the tail end of dealing with prostate cancer, so I just thought, ‘Fuck it,’ you know?

“Maybe I should have drunk more like Keith [Richards],” he goes on. “I don’t fucking know how those guys do it, but more power to them.”

Health problems aside, Stein lives comfortably now, splitting his time between the Manhattan apartment and a larger place in upstate New York. “God knows what’s going to happen in the world,” he says. “We might have to retreat to the woods.” Stein still has to grind, though, and makes an income through selling the photographs he has taken since the 1970s. “The music business, there’s a small percentage of people who are at the top, and then there’s a vast percentage below them who are just day-to-day working schlubs,” he says. “We almost got there, but I never quite see Blondie as A-list. I see it as this big cult band, anyway.”

Still, Blondie seem to be finding a new generation of fans: last year, the band played sets at Coachella and on the Pyramid stage at Glastonbury, where the field swayed as one to Heart of Glass, conducted by Harry, now 78, in a mirrored visor and CBGB T-shirt. “We are certainly appreciated, we have a lot of credibility for being authentic,” says Stein. “Whereas some people who are higher up the music food chain might be construed as having sold out a little more than we did.”

Stein laughs, “As I always say: selling out means that you got paid.”