There’s nowhere on Earth, perhaps, where you are reminded that rock music matters quite so much as the northwest of England. It’s there in Liverpool in the form of The Beatles, and the long mythology of scouse psychedelia. It’s there in Manchester in the way that the city’s musical and footballing successes have achieved a kind of global synonymity.

“If you go to Indonesia and say you’re from Manchester, they will say, ‘The Stone Roses, Oasis, The Smiths, David Beckham, Bobby Charlton, George Best,’” says Conrad Murray, an artist manager who has been at the centre of northwestern music for years – Courteeners, Blossoms and The Stone Roses are among the bands he has worked with. “It is such a big, interwoven thing, with music and football from Manchester.” The huge popularity of the recent Stone Roses and Manchester United collaboration with Adidas is a case in point.

The divide between the North West’s music industry and the London music industry has long been noted. Bands from the region, such as Courteeners, might play to tens of thousands at hometown shows in Manchester, but perform to dramatically smaller crowds elsewhere. Such bands, cynics would scoff, were local outfits on a grand scale, and they followed a pattern: they could be superstars at home, but little known in the capital. All of which rather misses the point. The question is, why do these bands seem to emerge from that particular region in such numbers?

The North West plays host to huge shows every summer. This month alone, Courteeners headlined Lytham Festival, which might not sound like a big deal until you note the other headliner is Shania Twain; and Jamie Webster (the scouse answer to Gerry Cinnamon) played Sefton Park in Liverpool alongside honorary northwesterners Catfish and the Bottlemen, who come from Wrexham, just across the Welsh border. In August, Blossoms will headline Wythenshawe Park.

Ground zero for the northwestern music boom – everyone agrees – was The Beatles. (Although Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burham has a bone to pick about that. “People forget The Hollies in Manchester,” Burnham says. “The Manchester scene gets a bit minimised because of what happened in Liverpool.”)

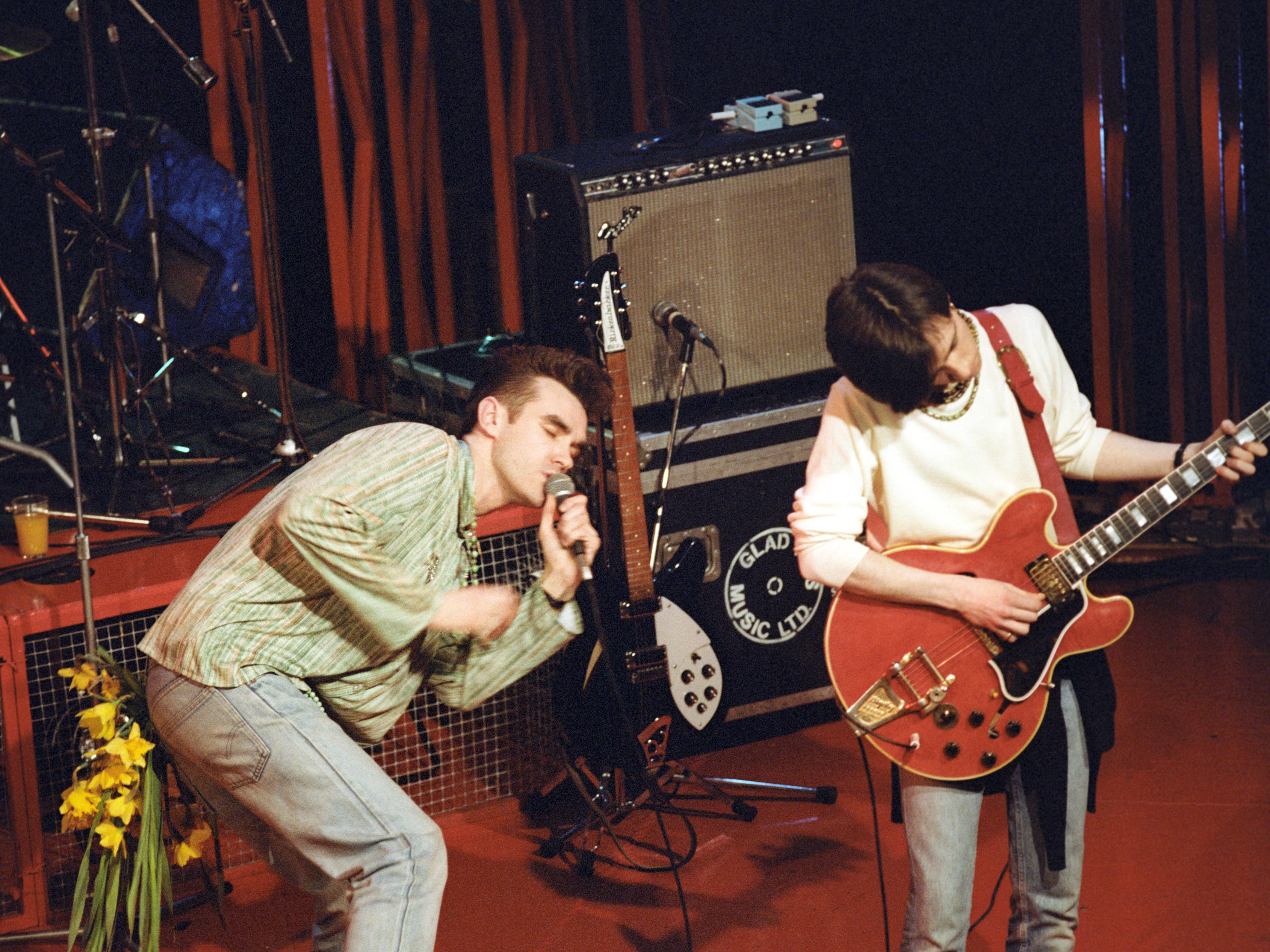

The Beatles (and The Hollies) may have been the first, but each generation has had its own guitar heroes – and bands enthuse and inspire each other. “Manchester and Liverpool are big cities, but they’re also small enough that ideas can cross-pollinate,” says regional cultural activist John Robb, a musician himself. “There’s one place that used to be a warehouse, where Joy Division rehearsed, where Buzzcocks rehearsed, where Slaughter and the Dogs rehearsed, where Johnny Marr’s band before the Smiths rehearsed. It was a cultural melting pot: all those bands were on the same corridor.”

Blossoms singer Tom Ogden puts it simply: “Being in a band, you meet lots of other bands, and a lot of them say they end up bigger in Manchester faster if they’re a guitar band. The North has an affinity with guitar bands.” It’s true that generations of bands – beginning with The Beatles and continuing with The Smiths, Echo and the Bunnymen, Oasis, The La’s, Happy Mondays, and on to the present day – have grown up with the idea that being a guitar band in the North West is a birthright. “The usual people sneer at this kind of thing,” Murray says. “But what other city has its own walk and its own hat, inspired by musicians? There’s no Norwich swagger, is there? But Manchester has that.”

The Manchester scene gets a bit minimised because of what happened with The Beatles

Andy Burnham, mayor of Greater Manchester

Perhaps the swagger comes from the effort the bands have to put in. According to Fran Doran of the Liverpool band Red Rum Club (who headline the 1,100-capacity Scale in London, but the 11,000-capacity M&S Arena at home), northwestern bands have to work harder, because they know no one’s going to sign them after three showcase gigs in hipster A&R hangouts. “From day one, when you set up a band in the North West, you know money’s not coming, you know London’s not going to come knocking,” he says. “And it’s going to take five to 10 years to do anything. So, the band mentality in the North West is collaboration – working together, rather than competition – which takes a while to work out.”

Murray is crucial to that collaboration, in his role with SJM music. Not only does he manage bands from the region, but SJM is also one of the UK’s biggest promoters. SJM is able to create virtuous circles in which its bands, in effect, promote each other. “They definitely sign a lot of northern bands,” Robb says. “And they make sure the bigger bands always take the next generation of bands out, who then in turn take the next generation of bands out.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

“It’s like a real-life Spotify recommendation,” Ogden says, “but in a live sense. It works well when you complement each other. That first Courteeners album was massive to me at school. It was the big album of the summer of leaving school. And we’ve played with them. We’ve played with Inspiral Carpets, James, The Charlatans, doing the rounds of classic Manchester bands, and you pick up fans there.”

It feels counterintuitive, Doran admits. “You’re competing on the charts and for festival slots. But the only way you can do it is by coming together and playing. Music has always been scenes, so if you create the scene, you create something they will come back to.”

That collaboration, Robb says, has always been the case, back to when his band The Membranes – from Blackpool – started playing in Manchester in the 1980s. “When bands started to make it, people would cheer them on,” he says. “I’d go to other cities and there’d be resentment: ‘How come they made it? We’re better than them.’ Whereas here it would be, ‘Great, they got out. Let’s keep on doing our thing.’”

The North West, too, offers groups the space to grow. Without the London music industry scrum, bands must learn their trade away from the spotlight. But there are ways to do that in Manchester and Liverpool, which is why so many northwestern bands seem to arrive in the capital already secure in their own ability to whip up a crowd. “Manchester has two huge arenas, and venues of different sizes,” Murray says. “You can move from a 100-cap room to a 200-cap up to a 500-cap and so on.” From there, it’s on to arenas. “There’s a structure in place for you to grow as an act.”

“We were selling out the Ritz [in Manchester] before we had a deal, which was quite a feat,” Ogden says of Blossoms. “We had SJM managing and a good agent, but we didn’t have the industry buzz. We had to deliver it to them. Labels did come a couple of times and passed on us, but we weren’t ready then. Maybe getting signed too early can sometimes hinder a band.” That said, he says, they wouldn’t have said no had they been offered a deal after one gig. “But we developed our sound more, and were able to come up with what became our first album.”

“I feel sorry for London bands,” Robb says. “One, because when they start, all the A&R turns up and they’re not ready, so everyone thinks ‘They’re not very good, are they?’ – whereas up here, if you’re in Wigan, you can spend years honing it to perfection.” Community is key, too, he adds. “Even with smaller bands, it’s like the way people doggedly support Accrington Stanley, week in, week out – there’ll be 1,800 people there, even if they’re doing really badly,” he says. “And some of the small bands will get that kind of following, while the bigger bands are like Man Utd and Man City – 40,000 will go to see Courteeners at Old Trafford, and it’s a very Mancunian thing that people come from all over the country for. And even if you don’t like the music, it’s a beautiful sight.”

Indeed, those big shows in the stadiums and arenas and parks of the North West are astonishing displays of fervour and hometown pride. At that Courteeners show at Old Trafford, fans were moshing and setting off flares right to the very back: it looked more like an Italian football crowd than a gig at a cricket ground.

“Hometown pride is a big thing,” Murray says. “How could young people not feel empowered growing up in a city with songs like ‘I Wanna Be Adored’, ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Star’, ‘Bigmouth Strikes Again’, ‘Not Nineteen Forever’, ‘Charlemagne’, ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ and ‘True Faith’?”

Does that pride ever metastasise into a weary contempt for southerners? “I don’t think it’s a ‘F*** you, London’ pride,” Doran says. “It’s more like, ‘We’ll be up here doing our thing, making our path.’”

Aa lot of musicians say they end up bigger in Manchester faster if they’re a guitar band

Tom Ogden, Blossoms

It helps that both Liverpool and Greater Manchester have local politicians who understand the importance of music, both economically and culturally. In London, it’s unheard of for music industry folk to praise elected politicians, but musicians up north pay tribute to Steve Rotherham, the mayor of Liverpool, and Andy Burnham, his counterpart in Greater Manchester.

“Music has been, over the decades, one of the UK’s strongest exports,” Burnham says, “both from a financial point of view and from a soft-power point of view. But how little time is spent on the airwaves, or in parliament or in any public forum, discussing what this export industry needs?” Music is taken for granted, is his point. “And it really mustn’t be. This has to be talked about as a top-order export for Britain – but it’s almost as if people think music will just find its way.”

Burnham puts his money where his mouth is. For example, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority has agreed to provide buses to transport fans to the giant outdoors show Blossoms are playing at Wythenshawe Park this summer. And he’s committed to helping local musicians with the mountains of bureaucracy that make touring abroad in the post-Brexit world such a chore. It’s not just him, he says: across the region, there’s a generation of local politicians who’ve grown up with this music and understand its cultural and social importance.

A generation of politicians, a generation of musicians, and a generation of fans, in fact. And what everyone stresses is that rock music in the North West isn’t a fashion. It’s part of the fabric of life; a generational thing. “It’s in the DNA,” Tom Ogden says. “My parents were at Spike Island to see The Stone Roses. My mum was at Maine Road, and I would sit and watch videos of Oasis. Why do people love guitar bands here? I put it down to their parents’ record collections.”