By Sergei Goryashko, BBC Russian

Reuters

ReutersRussian President Vladimir Putin frequently boasts that his country is leading the world in developing hypersonic weapons, which travel at more than five times the speed of sound.

But a string of Russian physicists working on the science underlying them have been charged with treason and imprisoned in recent years, in what rights groups see as an overzealous crackdown.

Most of those arrested are elderly, and three are now dead. One was taken from his hospital bed in the late stages of cancer and died soon afterwards.

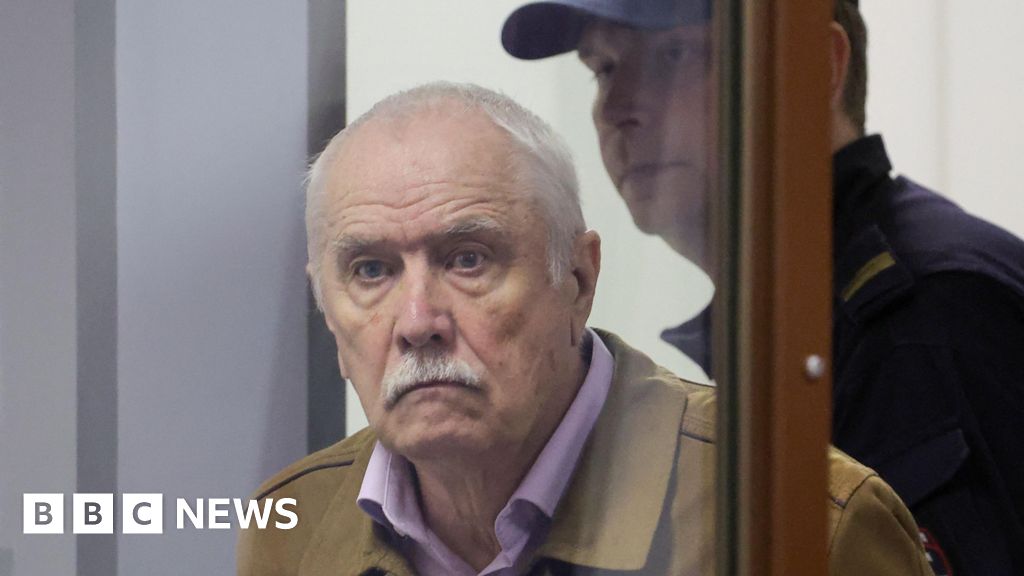

Another is Vladislav Galkin, a 68-year-old academic, whose home in Tomsk in southern Russia was raided in April 2023.

Armed men in black masks arrived at 04:00, digging through cupboards and seizing papers with scientific formulae on them, a relative says.

Mr Galkin’s wife, Tatyana, says she has told their grandchildren – who liked to play chess with him – that he’s on a business trip. She says Russia’s security service, the FSB, has forbidden her from speaking about his case.

Kolker family

Kolker familySince 2015, 12 physicists have been arrested who are all associated in some way with hypersonic technology or with institutions that work on it.

They are all charged with high treason, which can include passing state secrets to foreign countries.

Russian treason trials are held behind closed doors, so it’s not clear exactly what they are accused of.

The Kremlin has said only that “the accusations are serious” and it can’t comment further because special services are involved.

But colleagues and defence lawyers say the scientists weren’t involved in weapons development and that some of the cases are based on them openly collaborating with foreign researchers.

And critics suggest the FSB wants to create the impression foreign spies are chasing weapons secrets.

Getty

GettyHypersonic refers to missiles that can travel at extremely high speeds and also change direction during flight, evading air defences.

Russia says it has used two types in its war on Ukraine – the Kinzhal, launched from an aircraft, and the Zircon cruise missile.

However, Kyiv says its forces have shot down some Kinzhal missiles, raising questions about their capabilities.

As the technology has been developed and deployed, the arrests have continued.

Shortly after Mr Galkin’s arrest in April 2023, he was remanded in court on the same day as another scientist, Valery Zvegintsev, with whom he had co-authored several papers.

The state-owned news agency Tass has cited a source saying Mr Zvegintsev’s arrest may have been prompted by an article published in an Iranian journal in 2021.

Tomsk Polytechnic Institute

Tomsk Polytechnic InstituteMr Galkin and Mr Zvegintsev are both named on an article about air intake mechanisms for high-speed aircraft published by the journal.

In summer 2022, the FSB arrested two colleagues from the same institute as Mr Zvegintsev – its director and the former head of a laboratory for work on aerodynamics at high-speeds.

Employees from the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics (ITAM) penned an open letter in support of their three arrested colleagues.

Now removed from the institute’s website, it said they were known for “brilliant scientific results” and had “always remained faithful” to their country’s interests.

It said the work they had shared publicly had been repeatedly checked for restricted information by ITAM’s expert commission – and none had been found.

ITAM

ITAM“Hypersonic is a topic you are now obliged to put people in jail for,” says Yevgeny Smirnov, a lawyer with First Division, a Russian human rights and legal organisation.

Mr Smirnov defended scientists and others accused of treason in court before he moved from Russia to Prague in 2021, fearing repercussions from his work.

He says none of the dozen scientists had anything to do with the defence sector, but were studying scientific questions such as how metals deform at hypersonic speeds or the effects of turbulence.

“This is not about making a rocket, but about the study of physical processes,” he says, and points out that findings may be used later by weapons developers.

The arrests had started a few years earlier with Vladimir Lapygin. Now 83, he was jailed in 2016 but released on parole four years later.

He had worked for 46 years for the Russian space agency’s main research institute, TsNIIMash.

Bauman Moscow State Technical University

Bauman Moscow State Technical UniversityLapygin was convicted over a software package for aerodynamic calculations that he sent to a Chinese contact. He says he sent a demo version as part of discussions about potentially selling the full package on behalf of the institute.

But he maintains the version he shared did not contain any secret information, just an example that had been “repeatedly described in open publications”.

Lapygin told the BBC all those arrested apparently in connection with hypersonics “had nothing to do with” developing weapons.

Another scientist detained was Dmitry Kolker, a specialist at the Institute of Laser Physics, also in Siberia, who was arrested in 2022 while he was in hospital with advanced pancreatic cancer.

His family said the charges against him were based on lectures he had delivered in China, but that the content had been approved by the FSB and that an agent travelled with him.

Kolker died two days after his arrest, aged 54.

Getty

Getty“There’s a conflict within the system,” says a colleague of one of the arrested scientists, who wished to remain anonymous.

Scientists are still expected to publish internationally and collaborate with foreign colleagues, “meanwhile, the FSB thinks contact with foreign scientists and writing for foreign journals is a betrayal of the Motherland”, they say.

The ITAM scientists feel the same. “We just don’t understand how to continue doing our job,” their open letter said.

“What we are rewarded for today… tomorrow becomes the reason for criminal prosecution.”

They warn that scientists are afraid to engage in some areas of research, while talented young employees are leaving science.

The letter was a rare example of public support. The other institutes where arrested scientists worked have not commented.

Reuters / Russian defence ministry

Reuters / Russian defence ministryOther cases are also understood to relate to international collaboration.

An investigation into two other scientists was related to Hexafly, a European project to develop a hypersonic civilian aircraft, according to the lawyer Mr Smirnov, who worked on the case.

That project, now finished, was led by the European Space Agency and began in 2012.

The agency told the BBC “all technical contributions and exchanges were agreed and foreseen” in a co-operation agreement between the Russian and European parties involved.

Both scientists were sentenced to 12 years in prison last year, though Russia’s Supreme Court has ordered a retrial of one of them.

Other arrests related to a study into the aerodynamics as a space vehicle re-enters Earth’s atmosphere.

It was funded by a European Union scheme and run by the von Karman Institute of Fluid Dynamics in Belgium.

FSB investigators were concerned about a rounded cone shape that looked like a warhead in research that one of the scientists, Viktor Kudryavtsev, sent to the von Karman Institute, according to his widow, Olga.

The institute says the programme, which ran from 2011 to 2013, “very clearly excluded military research”. It says it “could not find any trace of disclosing secret information” by Kudryavtsev’s team.

Shiplyuk family

Shiplyuk familyHuman rights groups see a pattern.

Mr Smirnov says that, in private conversations, FSB officers have admitted to him that cases about sharing hypersonic secrets were being opened “to satisfy the wishes of those higher up”.

He believes the FSB wants to give the impression that spies are hunting Russian missile secrets “to flatter the ego” of Mr Putin.

The cases come amid a wider rise in treason cases.

Sergei Davidis, who leads work supporting Russian political prisoners at the Memorial human rights centre, speaks of an “atmosphere of spy mania and isolationism”, especially since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Speaking from Lithuania, where his organisation moved after it was banned in Russia, Mr Davidis says he believes the FSB, keen to show it is delivering, “builds up its reporting statistics through the fabrication of cases”.

But he believes there may be other factors in the arrests of scientists, such as competition for state contracts, or even a Kremlin message of dissatisfaction aimed at all scientists involved in hypersonics.

Mr Smirnov says the FSB sometimes offers more lenient sentences if suspects confess and implicate others.

Kudryavtsev was offered a plea bargain under which he would admit guilt and point the finger at someone else, according to his widow, Olga.

He refused. He died of lung cancer in 2021, aged 77, before his case came to trial.

Lefortovo court press service

Lefortovo court press serviceRetired FSB General Alexander Mikhailov says the FSB “must ensure the confidentiality” of military technology.

He says “undoubtedly” that there must be “substantial grounds” for severe sentences such as the 14-year prison term handed down in May to one of the three ITAM scientists, Anatoly Maslov.

Gen Mikhailov says the current spike in treason cases is the product of the expansion of freedoms and democracy in the 1990s.

He says this led to a change in attitude from Soviet times, when he says those with access to state secrets were “thoroughly vetted” and “understood the responsibility” of disclosing them.

“Some people were talking too much and leaks appeared,” he adds.

As for Mr Galkin, it is now over a year since the masked agents arrived. His relative says he spent the first three months in solitary confinement.

Tatyana, his wife, says she is able to speak to him by phone through a glass partition and recently even considered asking to be arrested too “because he just sits there, day after day”.

“I could ask them to put me in the same pre-trial detention centre. It would be easy enough – you just have to suspect someone of something.”

Other scientists arrested in Russia:

- Alexander Shiplyuk, 57, director of ITAM, arrested 2022, awaiting trial

- Alexander Kuranov, former director of St Petersburg Scientific Research Enterprise for Hypersonic Systems, arrested 2021, jailed for seven years in April 2024

- Roman Kovalyov, colleague of Vladimir Kudryavtsev at TsNIIMash, sentenced in 2020 to seven years in prison, died 2022