I was 19. Martin was 23. I was still at Oxford. Martin had just finished, but not yet published, The Rachel Papers. We started chatting at a book party about our favourite magazine, the New Statesman. The byline I most admired was that of someone called Bruno Holbrooke. Who was he, did Martin know? There was a pause and a sly smile. Then Martin grandly pronounced: “I. Am. Bruno Holbrooke.”

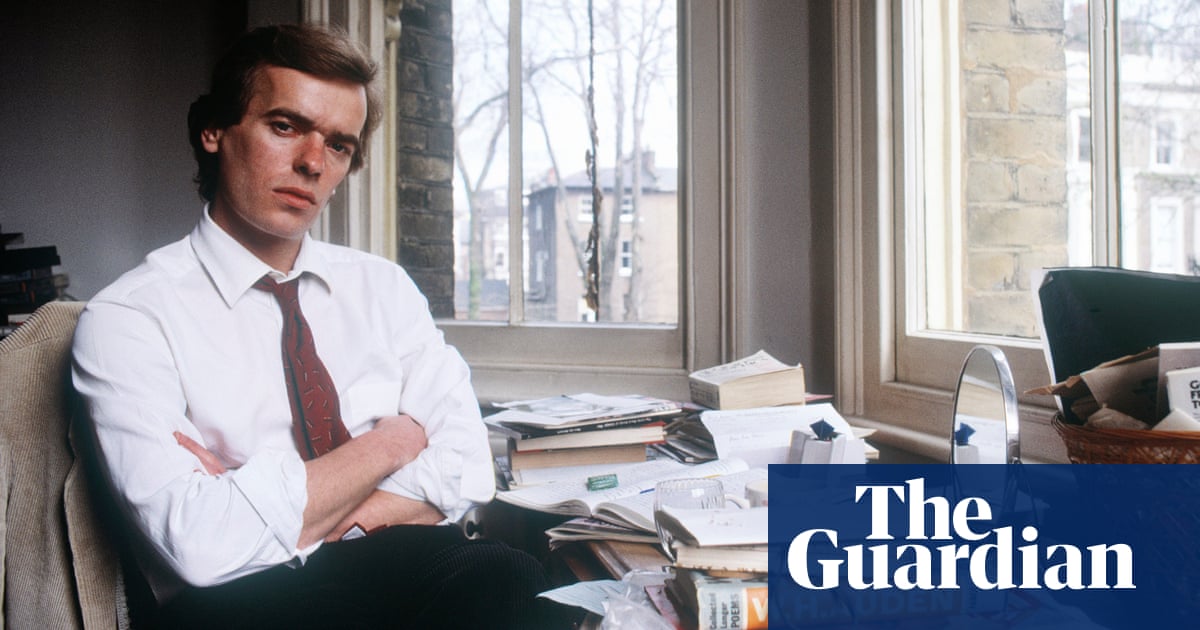

He was always Bruno to me after that. He called me Tiny. I was confident and vulnerable. He was cocky, beguiling and witheringly funny. Martin’s most seductive appeal was in his voice. Off the page, a rich, iconoclastic croak. On the page, a combination of curated American junkyard and British irony that hit the low notes so hard against the high that sparks flew and made every sentence electric. In a way, it matched his reading habits: if readers of the future want to know how an abiding faith in classic literature could survive, and even thrive, in a world of redtops, porn mags and trash TV, they will surely turn to Martin before anyone else.

It was part of Martin’s comic traction to cast himself as a sexual flop in his youth. Opening his memoir-novel Inside Story, I was startled to read that, quote, “Tina rode into town and rescued me from Larkinland. If she hadn’t, I might still be there.”

Gallant, but it’s not what I recall. When I met him, he had already broken a heart or two at Oxford. There was also the daunting glamour of his literary parentage. Going to stay in Barnet, London, with him, Kingsley and Elizabeth Jane Howard was a terrifying test you had to pass. All that Kingsley said about me, apparently, was: “Nice tits.”

Martin’s insecurity was reserved for the reception of The Rachel Papers. His letters to me, written in a cramped hand on Times Literary Supplement notepaper, are full of anxiety and dread. “I enclose the enclosed so that you still have some faith in my grubby talents when I am assassinated in the press tomorrow morning.” Or: “Please call Cape and command them to send you the full galley, read it, think it’s good, then send it on to Craig Raine, with strict instructions that I want only hypocritical praise, none of his blunt Northerner crap.”

The novel’s publication, of course, turned him into a wunderkind. But how hard Martin worked. His letters are full of literary toil, reviews, magazine pieces, line-editing of others at his day jobs at the New Statesman and TLS.

At every one of the magazines I edited myself for the next four decades, the goal was to get Martin to write for me. And, loyally, he did. Whenever his copy arrived, it was Christmas Day in the office: so eagerly awaited, never a disappointment. Remember his unforgettable profile of Truman Capote? It appeared in one of my first issues of Tatler. “Never mind the interview. Let’s call an ambulance,” Martin wrote, on first sighting the ruined literary genius. “Or I can take him there in my briefcase, I thought, as I contemplated the childish, barefoot, nightshirted figure.” Who writes profiles like that today?

Martin knew how good he was, and meted out his treasures to lucky editors with a certain lofty care. One of my first calls when I got to Vanity Fair was to ask him to write a piece about a new play by David Hare. His first question was: “Do I have to see it?” I found myself wavering, knowing that whatever he filed would be better than anyone else’s. Over the years, he became graver, more wary perhaps, but unchanged in his satirical glee.

Last February Isabel arranged for me to visit Martin at their home in Brooklyn. They loved each other devotedly, to the death. It hurt to see him so frail, but he was still Martin, undiminished: “I went in to have this special chemo treatment,” he said. “The doctor’s office was full of posters of happy cured people, windsurfing.” The italics dripped with the delighted disgust that Martin reserved for that wishful – and peculiarly American – fraudulence.

Mostly he reflected on “this new stage”, as he called it with an aloof curiosity. “There is absolutely no spiritual dimension to any of this,” he said. “No one writes anything really good after 70, anyway. It feels all right to look back at my life as ‘then’ – the past, belonging to someone else. The only thing I regret is not knowing how all this” – he gestured – “turns out. I’d like to have seen Trump finally finished.”

The truth is that none of us gets to know how it turns out, because it keeps going and we don’t.

A few days later, I emailed Martin and asked him if he remembered the night, 10 years before, when I tripped at a PEN gala in New York, caught my absurdly high heel in a rug, and did a full faceplant. I lay there seeing stars, like Captain Haddock in Tintin, as New York’s literary lions hurried past. And then, lo! There was Martin, in his dinner jacket, cradling my head, looking down at me and saying: “T, Tiny, are you all right?”

Martin replied that he, too, remembered that night. He added: “I also remember treating you to egg and chips – three shillings and sixpence – in Parsons on the Fulham Road. A great flood of nostalgia. Will stay in touch. B.”

If only. Goodbye, dear Bruno. Catch you later.