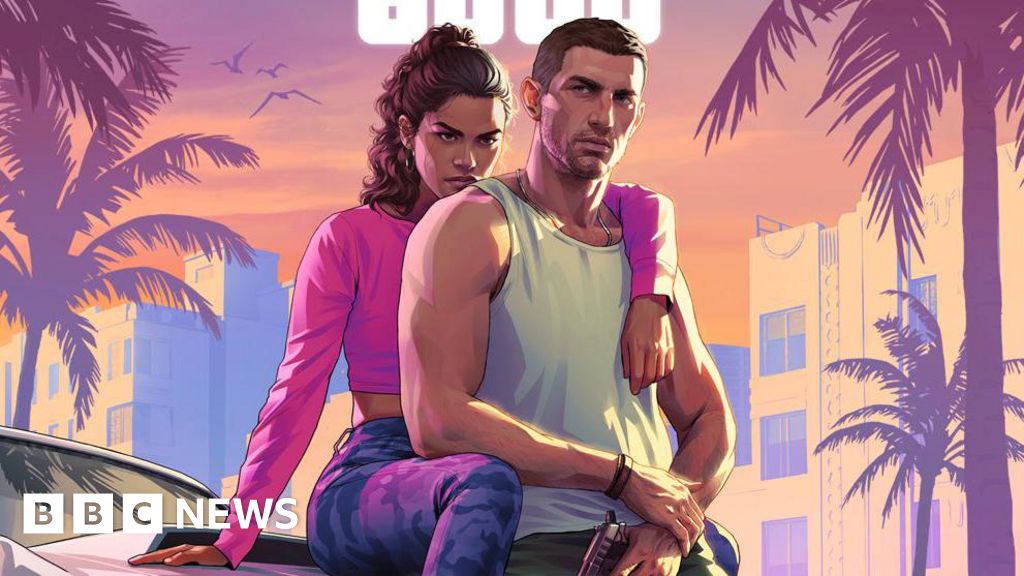

Rockstar Games

Rockstar GamesGrand Theft Auto makers Rockstar have battled hackers, tabloids and even US politicians, but they might not have expected fightback from an 80s pop star.

That’s what they got from Martyn Ware – the influential musician from synth pop band Heaven 17.

He told followers on X he had rejected a “pitiful” offer from the video game giant to use the group’s top ten 1983 track Temptation in the upcoming GTA 6.

In a series of posts, the musician said he and two fellow songwriters had been offered $22,500 (£17,200) between them – $7,500 each before subtracting fees.

He said the one-off sum was “pathetic”, considering the huge sums of money made by the game’s prequel, and Rockstar had refused to negotiate a higher amount.

While many came out in support of the musician, some posts suggested the band had missed out on finding a new generation of fans.

How does music get into games and films?

Artists use agreements known as synchronisation licences – or sync deals – to allow their music to appear in games, films, TV shows or adverts.

Licensing expert Alex Tarrand tells BBC Newsbeat it’s a system that’s been in use for decades, and can be “challenging” to navigate because there’s very little transparency.

“The scale is so wide,” says Alex, who’s worked for gaming brands including Xbox, Disney and EA.

“I’ve heard of sync licences from really, really indie artists being a couple of thousand dollars.

“I’ve heard of sync licences from major artists going into the millions and going from six digits into seven digits, astronomically higher.”

This lack of clarity can create difficulties, Alex says, because neither side knows what the other expects to pay or be paid.

It leads to a difficult question – “how much is this song worth?”

Negotiating higher and higher

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe company making a game will likely be thinking about how they want to use the song.

Is it going to be played on the game’s title screen, in a crucial cinematic sequence, or be heard on rotation during regular gameplay?

Martyn Ware did not specify how Rockstar proposed to use his track, and declined to comment further when BBC Newsbeat contacted him.

Rockstar did not respond to requests for comment but it’s been assumed the song would have been included among the hundreds of original and licensed tracks on GTA 6’s in-game radio stations.

In his tweet, Martyn pointed out that GTA 5 is reported to have taken in $8.6bn since its 2013 release.

Naomi Pohl is general secretary of the Musician’s Union, which represents about 35,000 people in the UK industry.

She says she isn’t surprised by Martyn’s reaction to Rockstar’s offer.

“I think what’s so frustrating and upsetting for artists is when they can see that the money they’re being offered or the royalties that they’re making from their music are so disproportionately low in comparison to how much a product is making,” Naomi tells BBC Newsbeat.

GTA 6 is expected to be a similar blockbuster success, and Naomi thinks it’s reasonable to factor that into expectations.

“Clearly a video game that’s making billions of pounds, it’s insulting to be offered a very low fee when you know you’re the music creator,” she says.

“They’ve selected it for a reason and you’re not being paid appropriately for it.”

Who decides the value of a song?

The artist, or whoever holds the rights to a song, gets the final say on the amount paid to use it.

Naomi points out that Martyn is a “long-established artist with a high profile already” and would likely have made sync deals in the past.

She points out that an artist might also have to factor in other parties, such as a song with multiple writing credits or a cut for a record label.

Both Naomi and Alex told Newsbeat that the $7,500 offer revealed by Martyn appeared low to them.

In one post, the artist said he would have accepted $75,000 or a suitable royalty deal.

“If he’s saying the value of my song is higher, then he’s right,” says Alex.

“There’s simply no disputing it.

“He has his own benchmarks for what his music has gotten in sync formats, and it sounds like they’re much higher than what that offer was.”

‘But think of all the exposure’

Getty Images

Getty ImagesResponses to Martyn’s original post suggested he had been foolish to turn Rockstar down because of GTA’s massive popularity.

The last game has sold 200m copies since its 2013 release and still ranks among the world’s most-played games thanks to its popular online mode.

In theory, a lot of them could hear your music and decide to search it out on a streaming service.

Alex says it’s hard to quantify this effect, although there are reverse examples where big artists have attracted huge numbers of players with in-game concerts.

And when the trailer for GTA 6 was released, featuring a track from US rocker Tom Petty, the song saw a massive spike in streams.

But, Naomi says, exposure doesn’t pay the bills and “streaming doesn’t sustain careers”.

In response to one critic, Martyn said that he could expect to make about $1,000 (£760) for every million listens.

Naomi says this figure sounded accurate, but it can vary from artist to artist.

“Even if you own your own recording, so there’s not a record label involved, still the streaming rates can be pretty low,” says Naomi.

“Most people have to go and perform live and that’s the way they make money.

“It’s not as easy to make money from recorded music as it used to be.”

A better way?

Alex is the co-founder of Styngr, a company that aims to make licensing music for games easier.

He says their biggest customer is Roblox, where it powers in-game boomboxes that player avatars can carry with them.

These stream music into the game, and can either be ad-supported or ad-free if users buy listening time via in-game microtransactions.

Alex describes this as an example of a “micro, micro-subscription” and says Styngr has plans to offer the ability to buy short snippets of music to accompany emotes – short dance move animations that are already a popular feature of Fortnite.

Styngr and Alex says the system allows artists, labels and developers to have much more transparency over how much music is streamed.

When asked, he says he believes everyone involved sees a better return than they would get from a streaming service.

Styngr is backed by Universal, Warner Music and Sony – some of the biggest record labels – and works closely with them.

For individual artists, union chief Naomi says new technologies can provide opportunities, but also challenges.

She says AI-generated music is a current focus, and the union has to “constantly update our agreements and our rates so that we are providing for the latest uses”.

Alex says sync deals won’t be disappearing any time soon, and there are situations where an artist will want to retain creative control over how their work is used.

“But I think there’s an opportunity to expand out of that mentality and avoid situations like we saw here, where both sides are probably pretty upset,” he says.