By Lucile Smith and Ben Steele, BBC TV Current Affairs

BBC

BBCThe Greek coastguard has caused the deaths of dozens of migrants in the Mediterranean over a three-year period, witnesses say, including nine who were deliberately thrown into the water.

The nine are among more than 40 people alleged to have died as a result of being forced out of Greek territorial waters, or taken back out to sea after reaching Greek islands, BBC analysis has found.

The Greek coastguard told our investigation it strongly rejects all accusations of illegal activities.

We showed footage of 12 people being loaded into a Greek coastguard boat, and then abandoned on a dinghy, to a former senior Greek coastguard officer. When he got up from his chair, and with his mic still on, he said it was “obviously illegal” and “an international crime”.

The Greek government has long been accused of forced returns – pushing people back towards Turkey, where they have crossed from, which is illegal under international law.

But this is the first time the BBC has calculated the number of incidents which allege that fatalities occurred as a result of the Greek coastguard’s actions.

The 15 incidents we analysed – dated May 2020-23 – resulted in 43 deaths. The initial sources were primarily local media, NGOs and the Turkish coastguard.

Verifying such accounts is extremely difficult – witnesses often disappear, or are too fearful to speak out. But in four of these cases we were able to corroborate accounts by speaking with eye witnesses.

Our research, which features in a new BBC documentary, Dead Calm: Killing in the Med?, suggested a clear pattern.

In five of the incidents, migrants said they were thrown directly into the sea by the Greek authorities. In four of those cases they explained how they had landed on Greek islands but were hunted down. In several other incidents, migrants said they had been put onto inflatable rafts without motors which then deflated, or appeared to have been punctured.

One of the most chilling accounts was given by a Cameroonian man, who says he was hunted by Greek authorities after landing on the island of Samos in September 2021.

Like all the people we interviewed, he said he was planning to register on Greek soil as an asylum seeker.

“We had barely docked, and the police came from behind,” he told us. “There were two policemen dressed in black, and three others in civilian clothes. They were masked, you could only see their eyes.”

He and two others – another from Cameroon and a man from Ivory Coast – were transferred to a Greek coastguard boat, he said, where events took a terrifying turn.

“They started with the [other] Cameroonian. They threw him in the water. The Ivorian man said: ‘Save me, I don’t want to die… and then eventually only his hand was above water, and his body was below.

“Slowly his hand slipped under, and the water engulfed him.”

Our interviewee says his abductors beat him.

“Punches were raining down on my head. It was like they were punching an animal.” And then he says they pushed him, too, into the water – without a life jacket. He was able to swim to shore, but the bodies of the other two – Sidy Keita and Didier Martial Kouamou Nana – were recovered on the Turkish coastline.

The survivor’s lawyers are demanding the Greek authorities open a double murder case.

Dead Calm: Killing in the Med?

In June 2023, an overloaded trawler flips in front of a Greek coast guard patrol boat. More than 600 men, women and children die in the water. But who is responsible, and are the coast guard at fault?

Watch on iPlayer or on BBC Two at 21:00 on Monday 17 June.

Another man, from Somalia, told the BBC how in March 2021 he had been caught by the Greek army on arrival on the island of Chios, who then handed him to the Greek coastguard.

He said the coastguard had tied his hands behind his back, before dropping him into the water.

“They threw me zip-tied in the middle of the sea. They wanted me to die,” he said.

He said he managed to survive by floating on his back, before one of his hands broke free from the ligature. But the sea was choppy, and three in his group died. Our interviewee made it to land where he was eventually spotted by the Turkish coastguard.

In the incident with the highest loss of life – in September 2022 – a boat carrying 85 migrants ran into trouble near the Greek island of Rhodes when its motor cut out.

Mohamed, from Syria, told us they rang the Greek coastguard for help – who loaded them onto a boat, returned them to Turkish waters and put them in life rafts. Mohamed says the raft he and his family were given had not had its valve properly closed.

“We immediately began to sink, they saw that… They heard us all screaming, and yet they still left us,” he told the BBC.

“The first child who died was my cousin’s son… After that it was one by one. Another child, another child, then my cousin himself disappeared. By the morning seven or eight children had died.

“My kids didn’t die until the morning… right before the Turkish coastguard arrived.”

Greek law allows all migrants seeking asylum to register their claim on several of the islands at special registration centres.

But our interviewees – who we contacted with the help of migrant support body Consolidated Rescue Group – said they were apprehended before they could get to these centres. They said these men would be apparently operating undercover – non-uniformed, and often masked.

Human rights groups allege thousands of people seeking asylum in Europe have been illegally forced back from Greece to Turkey and denied the right to seek asylum, which is enshrined in international and EU law.

Austrian activist Fayad Mulla told us he discovered for himself how secretive such operations seem to be in February last year, on the Greek island of Lesbos.

Driving towards the location of an alleged forced return after a tip-off, he was stopped by a man in a hoodie – who was later revealed to work for the police. He said the police then attempted to delete the footage of him being stopped from his dashcam and charge him with resisting a police officer.

Ultimately, no further action was taken.

Fayad Mulla

Fayad MullaTwo months later, in a similar place, Mr Mulla managed to film a forced return, published by The New York Times.

A group which included women and babies was unloaded from the back of an unmarked van and marched down a jetty onto a small boat.

They were then transferred onto a Greek coastguard vessel further away from the coastline, taken out to sea, and then put onto a raft where they were left to drift.

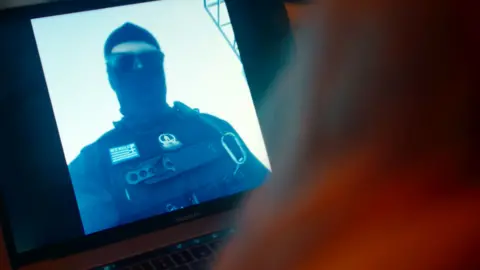

We showed this footage – which the BBC has verified – to Dimitris Baltakos, the former head of special operations with the Greek coastguard.

During the interview, he refused to speculate about what the footage showed – having denied, earlier in our conversation, that the Greek coastguard would ever be required to do anything illegal. But during a break, he was recorded telling someone out of shot in Greek:

“I haven’t told them much, right? It’s very clear, isn’t it. It’s not nuclear physics. I don’t know why they did it in broad daylight… It’s… obviously illegal. It’s an international crime.”

Greece’s Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Insular Policy told the BBC the footage is currently being investigated by the country’s independent National Transparency Authority.

An investigative journalist we spoke to based on the island of Samos says she began chatting with a member of the Greek special forces via the dating app Tinder.

When he rang her from what he described as a “warship”, Romy van Baarsen asked him more about his work – and what happened when his forces spotted a refugee boat.

He replied that they “drive them back”, and said such orders were “from the minister”, adding they would be punished if they failed to stop a boat.

Greece has always denied so-called “pushbacks” are taking place.

Greece is an entryway into Europe for many migrants. Last year, there were 263,048 sea arrivals in Europe, with Greece receiving 41,561 (16%) of those. Turkey signed a deal with the EU in 2016 to stop migrants and refugees crossing into Greece, but said in 2020 it could no longer enforce it.

We put the findings in our investigation to the Greek coastguard. It replied that its staff worked “tirelessly with the utmost professionalism, a strong sense of responsibility and respect for human life and fundamental rights”, adding that they were “in full compliance with the country’s international obligations”.

It added: “It should be highlighted that from 2015 to 2024, the Hellenic Coast Guard has rescued 250,834 refugees/migrants in 6,161 incidents at sea. The impeccable execution of this noble mission has been positively recognized by the international community.”

The Greek coastguard has previously been criticised for its role in the biggest migrant shipwreck in the Mediterranean for a decade. More than 600 people are feared to have died after the Adriana sank in Greece’s demarcated rescue area last June.

Greek officials have insisted the boat was not in trouble and was safely on its way to Italy, and so the coastguard did not attempt a rescue.