The rise of artificial intelligence has been rattling world leaders over its potential impact on politically sensitive areas from security to healthcare. Their next worry: employment.

At their annual summit last week in Italy, leaders of the Group of Seven big economies agreed to draft an “action plan” for how AI could affect work, employment and wages around the globe. Details of the plan are to be fleshed out at a meeting of G7 employment ministers in Italy 11-13 September – but, as one official involved in the discussions put it, “it’s a really important signal that the G7 has decided to focus on this aspect” of AI.

And that focus is long overdue, according to many labour economists who have been warning of the huge social and geopolitical consequences of AI in the workplace.

Estimates of the number of jobs “vulnerable” to AI range into the hundreds of millions, with some jobs automated and others transformed. The political consequences could be huge. Pessimists warn of widening wage gaps and geopolitical tensions, while optimists say AI could benefit disabled or lower-skilled workers and boost economic efficiency for all.

What’s needed, many economist say – and at their Italian summit the G7 leaders agreed – is much more global research and information-sharing. “It requires a lot of experimentation and scientific work to understand” the potential labour impact of AI, says Matthias Peissner, a research head at the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering in Stuttgart. “Occupations will change. But how? There are so many questions.”

‘Concrete actions’ promised

News of the G7 plan, though included in the leaders’ 36-page communique 14 June, got buried in the international media scrum around other issues at the summit, from Ukraine to abortion rights.

“We will launch an action plan on the use of AI in the world of work,” the G7 statement said on page 21. The plan will envisage “concrete actions to fully leverage the potential of AI to enable decent work and workers’ rights and full access to adequate reskilling and upskilling, while addressing potential challenges and risks to our labour markets.”

The decision mirrors a workplace “action plan” that member state ministers of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development commissioned at their annual meeting in Paris in May. And another organisation, the Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence initiated in 2019 by the French and Canadian governments, has also been pushing for action. In a report last year, the group bemoaned “a notable absence of discussions on the technology’s impact on work” among world leaders.

But that’s changing – as indicated by Pope Francis’ star turn at the summit, focusing his speech on AI. It could, he said, improve “access to knowledge, the exponential advancement of scientific research and the possibility of giving demanding and arduous work to machines. Yet at the same time, it could bring with it a greater injustice between advanced and developing nations or between dominant and oppressed social classes.” To avoid a dystopia, he concluded, human morality must stay in control of the machines.

The data so far

Part of the policy problem is the sheer speed with which AI is developing. Much of the research on labour impact to date was conducted before the bombshell launch of Chat GPT and other general-purpose, generative AI programmes last year. “It’s different from previous technologies”, says Stijn Broecke, a senior labour economist at the OECD.

An International Labour Organisation study last year estimated that 5.5% of jobs in advanced economies could be automated by AI, compared to 0.4% in developing countries (due to their heavier reliance on agricultural and other resource-based industries.) But a higher share of jobs – 13.4% in developed countries, and 10.4% in developing countries – could be “augmented”, or transformed by using AI tools for specific tasks.

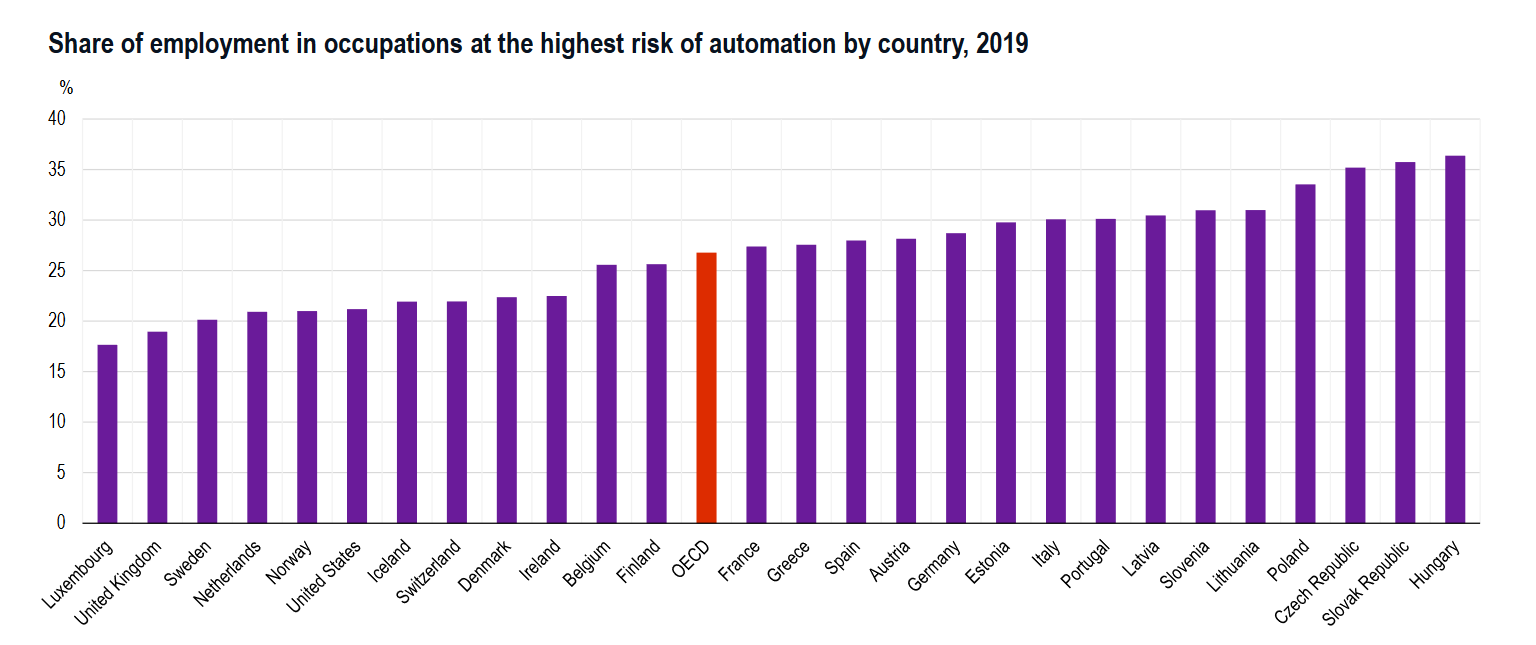

Even within regions, there will be big differences. In its annual global employment outlook, the OECD estimated that east European nations like Hungary and Slovakia have among the highest risks of job automation, while Luxembourg, the UK and Sweden have the lowest.

The potential impact also varies hugely by profession. An International Monetary Fund study suggested that truck drivers and dishwashers would be among the least affected – and professional dancers, not at all. Telemarketers, economists, lawyers and judges could be among the most affected.

Then, according to a GPAI research group, there’s a huge category of professions in the middle – the “big unknown.” This comprises 281 million people whose jobs could be automated or augmented by generative AI, but in ways we don’t yet understand. The group, whose work was cited in the G7 statement, urged research as well as new social protections, training and investment to ensure that, whatever the impact of generative AI, it’s positive rather than negative.

Research this year has also started turning up some encouraging results. So far, says Broecke, economists haven’t measured any actual loss of jobs due to AI; in fact, employment has continued growing in such highly skilled, and in-demand, professions as doctors and lawyers. And even within professions, there’s some evidence that where AI is used it helps make lesser-skilled workers more productive. Indeed, the overall economic effect could be positive: as workers get more productive with AI, goods and services could become cheaper – fueling more employment.

As an example, Broecke cites the introduction of bank cash machines in the 1960s and 1970s. At the start, widespread job losses were forecast among bank tellers. In fact, bank productivity – and employment – rose. With AI, a similar outcome is possible: “it will make us more productive.”

Problems ahead

But even so, economists warn, there are huge social and ethical problems ahead. As with any powerful new technology, some jobs will disappear and others arise – and the resultant turmoil may worsen inequality and strife. Other workplace risks include racial discrimination, loss of privacy, management-by-algorithm (as already happens in big Amazon warehouses) and more.

These issues are also now under study – in the G7, the OECD and other international groups, as well as national governments. The EU AI Act is the world’s first attempt at broad regulation to manage the multifarious risks of AI. So far in the US, where most of the hottest AI technology has arisen, legislators have been paralysed by partisanship and tech industry lobbying.

But as a start, more research could help the policy makers. For instance, says Peissner, we have to get beyond the broad, macro surveys on AI impact done so far – and focus in on specific professions and functions. There’s also the question of how to give workers a say in how these technologies develop. And, he notes, as big tech companies are leading AI, one might argue that “if they bring the technology to developing countries, shouldn’t they also bring education to those countries?”

“What we really need is to shed light on how we can react. How do we want to shape this future?”