BBC/Léa Guedj

BBC/Léa GuedjAn audible sigh of frustration drifted across the packed seats of courtroom “Voltaire” in Avignon’s Palace of Justice, as the lead judge, dressed in a scarlet robe, announced an unexpected but unavoidable delay to a trial that has gripped France.

“He is ill,” said Presiding Judge Roger Arata, indicating that this extraordinary case of 51 alleged rapists would be delayed for “one, two, three days” or possibly even longer, after it was revealed that Dominique Pelicot was too sick to attend.

His lawyer said later he had been taken to hospital.

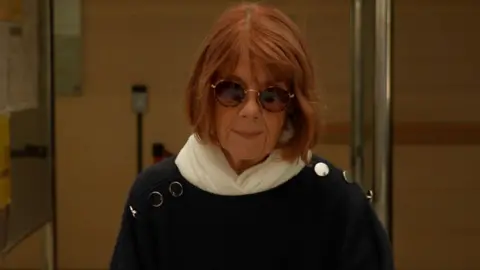

On the right edge of the courtroom, her head leaning gently against a wood-panelled wall, Gisèle Pelicot showed no visible emotion at the news that she would not, after all, be seeing her husband give evidence that day.

Last week, Gisèle Pelicot, 72, told the court that her calm demeanour masked a “field of devastation”, triggered by the instance, four years ago, when a French policeman had informed her that her apparently loving husband had, in fact, been drugging her for a decade and inviting strangers – more than 80 local men – to enter the family home, and the couple’s bedroom, to rape her while he filmed them.

She has waived her right to anonymity to highlight the danger to women of being drugged and sexually attacked – known as “chemical submission”.

It is little more than half an hour’s drive – through the gentle hills and vineyards that surround the looming, almost lunar landscape of Mont Ventoux – from Avignon’s courthouse to the quaint, medieval village of Mazan. The village was once briefly known for hosting British actress Keira Knightley’s wedding.

This is where the Pelicots lived, and where Dominique Pelicot filmed the local men that he had contacted online.

The mood in any place, at any one moment, is always hard to sum up.

“Honestly, no-one here gives a damn,” said a local caterer, Evan Tuvignon, leaning on his shop counter and suggesting that people were fed up with the whole case.

But several women told us the village was not only in shock, but that the unfolding revelations in court were causing new tensions in Mazan and the surrounding villages.

The names of the accused were recently shared widely on social media, and some of those men have since complained to the court that they, their families and children are now facing harassment on the streets and at school.

Two local women, loading their car on a narrow street in Mazan, said they’d seen the names and had recognised at least three of them.

“It creates tensions, you can imagine. You don’t know who to trust on the street. I’m relieved that I’ll be moving away from this village soon,” said Océane Martin, 25.

But beside her, Océane’s mother, Isabelle Liversain, 50, raised another, deeper concern.

It has been revealed that, while the police have already identified and detained 50 of the men whose images appeared on Dominique Pelicot’s hard drive, another 30 suspects – as yet unnamed and untraced – remain at large.

“So, we know 30 out of 80 still haven’t been caught. There are tensions here because people don’t know if they can trust their neighbours. You ask yourself – is he one of the 30? What is your neighbour getting up to behind closed doors?” said Isabelle Liversain in a voice sharp with frustration.

But Mazan’s 74-year-old mayor, Louis Bonnet, sought to play down those tensions, arguing that most of the alleged rapists came from other villages and seeking to frame the Pelicots as outsiders who hadn’t lived there long.

He went further, saying the threats against the accused and their families were to be expected.

“If they participated in these rapes, then it’s normal that they’re considered targets. There has to be transparency about everything that happened,” he said, while also condemning the accused and their actions.

In his interview with us, Bonnet talked about the case itself, and in doing so veered towards the sort of attitudes that have already sparked fury in France as well as deep admiration for Gisèle Pelicot’s courage in confronting them.

“People here say ‘no one was killed’. It would have been much worse if [Pelicot] had killed his wife. But that didn’t happen in this case,” Bonnet said.

Then he went on to address Gisèle Pelicot’s experiences.

“She’ll have trouble getting back on her feet again for sure,” he agreed, but suggested her rapes were less troubling than those of another victim in the nearby town of Carpentras who “was conscious when she was raped… and will carry the physical and mental trauma for a long time, which is even more serious”.

“When there are kids involved, or women killed, then that’s very serious because there’s no way back. In this case, the family will have to rebuild itself. It will be hard. But they’re not dead, so they can still do it.”

When I suggested that he was seeking to play down the gravity of the Pelicot case, he agreed.

“Yes, I am. What happened was very serious. But I’m not going to say the village has to bear the memory of a crime which goes beyond the limits of what can be considered acceptable,” he said.

His phrasing seemed clumsy. He was condemning the case. He didn’t want his village to be branded by it forever.

But he also appeared to belittle Gisèle Pelicot’s trauma.

I pushed back once again. Many women believed this case had exposed particular types of male behaviour that needed to change, I said.

“We can always wish to change attitudes, and we should. But in reality, there’s no magic formula. The people who acted in this way are impossible to understand and shouldn’t be excused or understood. But it still exists,” replied Bonnet.

Inside the courtroom in Avignon, some of the accused – the 18 now in custody – sat inside a special glass-walled section watching the proceedings. A white man with grey, straggly hair stroked his bearded chin. Nearby, a younger black man seemed to be dozing.

Earlier, dozens of their fellow accused – those not in custody – jostled beside journalists in a large queue outside the courtroom.

Most of the men sought to hide their faces with masks, but a few did not. A larger man shuffled forward on crutches. Someone pulled a green hood down over their face.

French law offers the accused some protection from being identified in the media, but Gisèle Pelicot has declined her own legal right to privacy, preferring instead to become a symbol of defiance for many French women.

“She has shown such dignity and courage and humanity. It was a huge gift to [French women] that she chose to speak to the whole world in front of her rapist. They said she was broken. But she was so inspiring,” said Blandine Deverlanges, a local activist attending the court today.

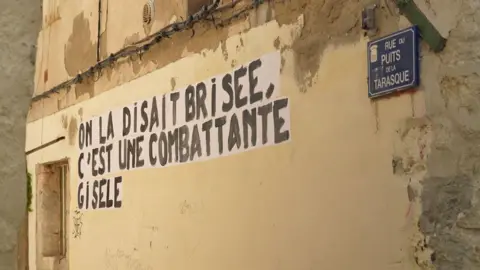

She and her colleagues have recently painted slogans on walls around Avignon. One reads: “Ordinary men. Horrific crimes.”

CHRISTOPHE SIMON/AFP

CHRISTOPHE SIMON/AFPSeated beside her mother, the couple’s daughter, Caroline, 45, did not hide her emotions.

She was recently shown evidence that her father had taken pictures of her, without her knowledge or permission. She believes she was drugged by him too and has become a campaigner on the issue of rape and drugs – a problem many experts believe is woefully under-reported and under-investigated in France.

At times, in court, Caroline frowned or raised a hand to her face in apparent frustration or disgust, as various defence lawyers raised objections or debated procedural issues. A police officer began giving evidence, speaking in the strong accent of southern France. Bright sunshine flooded through a skylight above the judges’ heads.

The atmosphere in the elegantly decorated court was calm, but it felt shocking, nonetheless, to see the family – mother, daughter and at least two sons – seated just metres from so many alleged rapists, now all with their masks removed.