When the late, great Fela Kuti drummer Tony Allen arrived at his Seventies-boho basement studio in Paris one morning in December 2016, he seemed unsure of the stranger with the flyaway hair and thicket of beard who was setting up in the live room. Dennis something? From some band called The Foals?

“He was smaller than I imagined him to be, quieter and more introverted,” says Yannis Philippakis of Allen, the French-Nigerian drum legend whom he met for the first time eight years ago. “I interpreted him as cranky, but it was early, it was December, he was probably like, ‘Who’s this guy that’s come off the Eurostar?’” says Philippakis, reminiscing over fruity lagers in the beer garden adjacent to his Peckham studio. Did Philippakis have to explain Foals, one of the UK’s biggest rock bands of which he is the frontman, to the 75-year-old musician? “I didn’t, but only because he didn’t ask.”

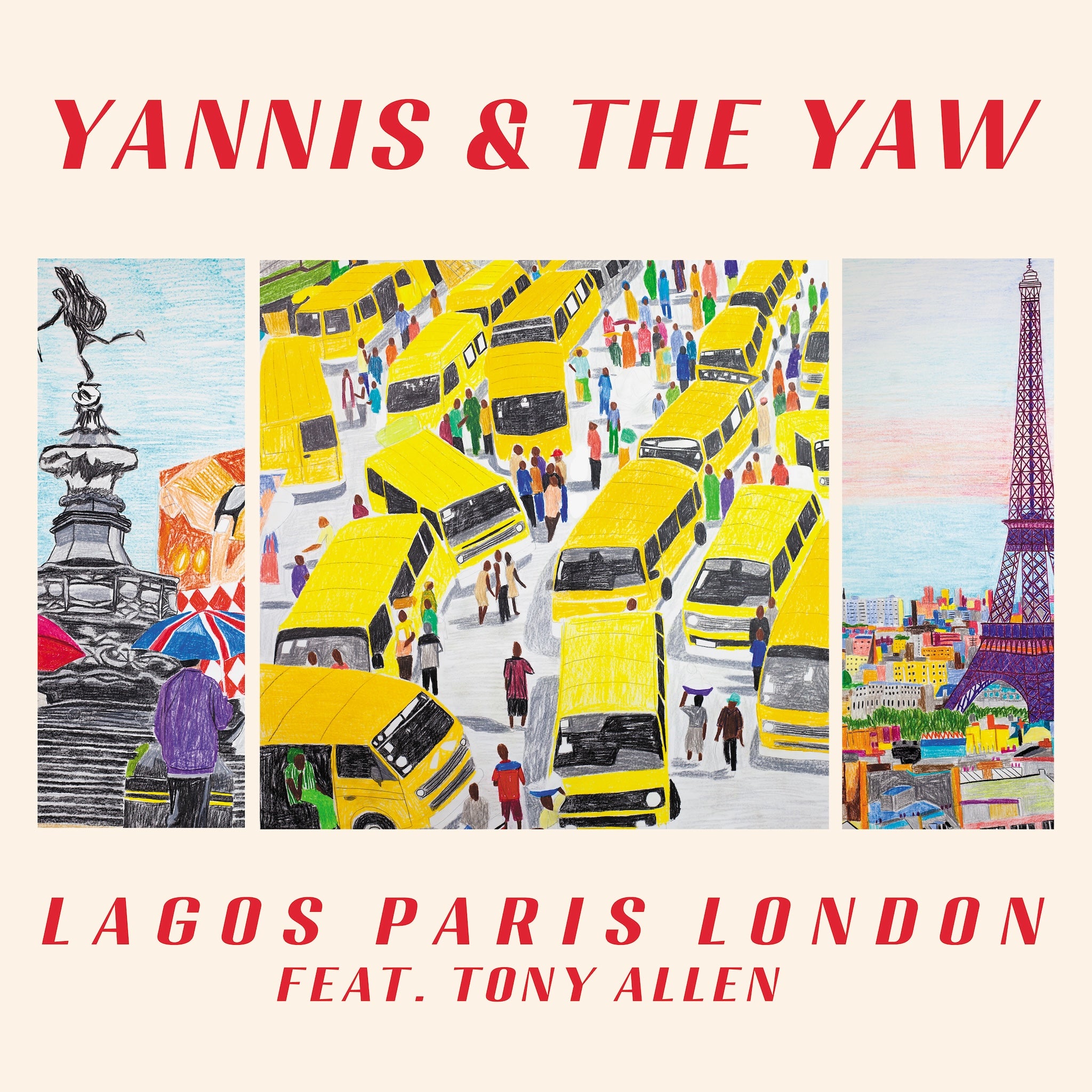

It was a meeting that would result in Lagos Paris London, the pair’s long-awaited EP out this week as Yannis & the Yaw. Their music is bred from the same stable as Foals, but with their Afrobeat and highlife elements drawn more directly from the source. On “Rain Can’t Reach Us”, Philippakis’s itchy ambience and brooding guitar work is wedded to earthy Allen polyrhythms. While “Clementine” finds Allen providing jazz-funk swing to Philippakis’s sun-kissed evocation of an obsessive holiday romance.

As a sometime drummer with Gorillaz, The Good, The Bad & The Queen, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sebastien Tellier and others, Allen was no stranger to a cool leftfield collaboration. But Philippakis was particularly attuned to the drummer’s instinctive rhythms, having grown up listening to his South African mother’s Afrobeat and the Sounds of Soweto album rather than The Beatles or Led Zeppelin. During the early days of Foals, Philippakis filled the band’s shared house in Oxford with the sounds of Fela Kuti. When they finally got together, the magic was instantaneous.

“One of the most exciting musical moments of my life was when I went into the live room to set up my amp,” Philippakis recalls. “Tony quite quietly came into this drum booth, and I almost didn’t notice. I was playing the first riff off [opening song] ‘Walk Through Fire’, because it’s the kind of riff that I would soundcheck with, the kind of riff that’s part of my musical DNA. And then all of a sudden, I could just hear Tony playing next to me. It was a thrilling moment.” That first session produced three of the EP’s five tracks; what he remembers most is the twinkle in the drummer’s eye as their connection fused. “It was like a dance,” he says. “The guitar and the drums were playing out some type of dance between us.”

A steely-eyed but amenable presence, now far removed from the angst-riddled young man of early Foals interviews, Philippakis is enjoying a period of relative musical solitude. Foals have paused activity following 2022’s seventh – and seventh Top Ten – album Life Is Yours, the climax of 15 relentless years on the album cycle treadmill. Now every day, Philippakis walks to the studio from his Camberwell home to make music for his friend Alexander Zeldin’s theatre production The Other Place (opening at the National in October) happily alone.

“We toured so much that by the end of Life Is Yours I felt like we just wanted to be at home, and feel solid ground underneath my feet,” he says. “It’s a bit of a holiday from myself, in a way.”

It’s a slower pace that Philippakis picked up from working with Allen. “I really learnt a lot about his rhythm in the studio,” he says. “I think I had quite an uptight, slightly anxious energy about wanting to milk every minute of the time in the studio and Tony had a very different, much more leisurely [approach]… you have to wait for the right moment to start to record.”

They also had to wait, on occasion, for drummer’s friend and technical assistant Jack Daniels to do his work. “It would be pot in the day and whisky at night,” Philippakis grins. “You could hear it in some of the takes – they would get really sloppy. [Allen] taught me how to pilfer whisky from studio budgets because he’d take these bottles home. He was mischievous in that way; he was fun and super young at heart.” His lip tightens. “It’s a shame we didn’t get to go on tour together. We would have caused havoc.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

On 30 April 2020, Allen died from an aneurysm in Paris, aged 79. “I just couldn’t really believe it,” Philippakis says, hardened to the loss now. “I had felt like he would have been around forever.” His main regret is that he had become complacent over finishing the project, allowing his work with Foals to stall their progress. “We thought we had more time than we really did. All of this would have been more rewarding had we completed it at the time,” he says. “But obviously there’s something magical in having just gotten to work with him. The fact that our axes got to cross is a genuine, proud moment. It feels like something precious.”

It was an important tribute, then, for Philippakis to eventually complete, release and perform the tracks. Comprising Philippakis and a band that includes Allen’s Parisian players and studio engineers, Yannis & the Yaw are set to play four shows across Northern Europe in September, culminating at a sold-out Camden Koko.

Given the EP’s material, the shows will be celebratory sets that bristle with a serious undercurrent. “Night Green, Heavy Love”, for instance, stalks in on Allen’s swampland percussion, a dusky vibe over which Philippakis whispers conspiratorially about “chasing the dragon”. “It’s not necessarily [about] addiction, but it’s a drug-taking song,” he explains. “It’s just from being younger and, like most 16- or 17-year-olds, experimenting with drugs. I was thinking about chasing the dragon and how intense those experiences with substances can be when you’re young.” The dragon in question isn’t heroin, he stresses. “No, I haven’t had heroin problems in my past.”

As they were recording in Paris during the refuse strikes of 2016, Allen encouraged Philippakis to sing about the unfolding discontent surrounding the sessions. Hence “Under the Strikes” is a highlife carnival through trash-clogged streets. “I was literally having to jump out of the way of football-sized rats,” Philippakis says. “There’s this sense that the city was born in a golden age [but] everything’s past its peak, and you’re living in the cooling ember of something that was great before.”

“Walk Through Fire” pays even greater tribute to the revolutionary tone of Allen’s work with Fela Kuti, dropping the listener in the heat of an urban riot: “The city burns while it says my name/ I walk through fire, I walk through flame.” When writing the lyric, he envisioned old black-and-white news footage of Sixties unrest in France or Greece. “That type of European left-wing revolutionary spirit has metastasized and come back as a right-wing expression, in the West anyway,” he says. “There’s this violence. Some things that are happening now, they feel anachronistic, that they belong to the past.”

Lots of people’s idea of the UK, rightly or wrongly, is one that there’s a sense of good sportsmanship or fair play. Something’s happened where we’ve hit this cavity where you realise it’s totally rotten on the inside

The narrowness with which France recently avoided a far-right Le Pen government was, he says, “abhorrent and terrifying” – as were the recent racist riots in the UK. But he feels optimistic about our political future here. “Hopefully common sense and clear-headedness and plurality and radical acceptances are going to win in the UK,” he says. “There’s something about Le Pen as a political force that’s been there for a long time and has hardened and has gained power. Thankfully, in the UK the extreme right wing seems to be more fractured and disparate and less organised. Especially now that Labour are in, I feel more optimistic. I think that getting the Tories out was f***ing great.”

The fraying edges of our society leave Philippakis aghast. He cites river pollution, energy company price gouging and flagrant Tory immorality as being particularly shocking. “Lots of people’s idea of the UK, rightly or wrongly, is one that there’s a sense of good sportsmanship or fair play, that things are above board,” he says. “And something’s happened where we’ve hit this cavity where you realise it’s totally rotten on the inside.”

His future is more pleasantly uncertain. The Yaw is now a hanging project, a means by which Philippakis might decide to collaborate with other musicians in the future, as cultural pilgrimages into Malian guitar music or his Greek heritage. “As I’m getting older, I feel almost like a familial obligation,” he says. “There’s something really rich to be mined, something to do with Greek music from the past and how Greek culture is vanishing through tourism and through homogenous globalisation.” He has recordings of his father, an architect and maker of Greek instruments, singing folk songs in the Sixties, which he’s considering incorporating.

As for Foals, they’re enjoying their brief hiatus before new writing sessions commence on what Philippakis hopes will be a more urgent, leftfield and hopefully definitive eighth album. “The thing that’s eluded us in some way is making the one album that is the defining record that balances the experimentation and the musicality with the hooks,” he says, amazed that this “mad family” remains harmonious as its 20th-year approaches.

The Yaw, then, doesn’t represent a break away for Philippakis, but a broadening out. “I don’t see myself as being defined in this mono way, where I’m meant to just be tethered to the band,” he says. “I want to be creative until my last day and in order for that to happen and for it to not get stilted, I want to be creative on different fronts. I just want to be wildly creative – that’s the way I want to use my time while I’m on the planet.”

Of all the things he learnt from Tony Allen, then, perhaps the greatest was to grab music while you can.

‘Yannis & The Yaw featuring Tony Allen’ is out on 30 August via Transgressive Records