When it comes to space exploration, there is one name that has, quite literally, rocketed itself to the top of everyone’s mind. Since SpaceX was founded in 2002, the company has launched their Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets on more than 370 missions, and spearheading the company is Elon Musk, the controversial businessman who also holds the reigns at Tesla and X (formerly Twitter).

In the new book “SpaceX: Elon Musk and the Final Frontier” (Motorbooks), science journalist Brad Bergan creates a fascinating picture of Musk’s vision and how he came to build a business that has become vital to national agencies like NASA, and other ventures that have ambitions of exploring space.

In this excerpt, he explores the enormous costs involved with space travel, and why, despite the potential riches at stake, it might just be better to stay grounded for a while still.

“If we don’t improve our pace of progress, I’m definitely going to be dead before we go to Mars,” said Elon Musk at the Satellite 2020 conference in Washington, D.C., according to a report from the Los Angeles Times. “If it’s taken us 18 years just to get ready to do the first people in orbit, we’ve got to improve our rate of innovation or, based on past trends, I am definitely going to be dead before Mars.”

It was a sobering reflection of a dark reality that gives anyone pause. Whether you love the promise of space travel, hate the toll modern industries levy on the poor, or are completely indifferent — death is a constant reminder that no matter what you do, or what you build, its final fate will likely happen long after your life has expired.

This is something most readers will have in common with Musk: A human journey to Mars is very likely in the coming decades. But a settlement on Mars developed enough to support non essential personnel, with interplanetary tickets cheap enough to serve as a viable escape hatch from Earth for at least the middle class of the United States? Don’t bank on it in your lifetime — at least, not within the time frame where the physically healthiest among us could withstand the environmental and psychological pressures of the months-long journey there.

In terms of cost, Musk has said he’s “confident” that moving to Mars could eventually cost less than $500,000 — and “maybe even” less than $100,000. These figures were given in 2019. Not to hold a very rough estimation to an economic magnifying glass, but that’s nearly $600,000 and $120,000, in 2023 dollars, adjusted for inflation.

Still, that latter figure is in reach of a significant portion of the US workforce. In 2023, the average yearly income was $56,940 (before taxes). If inflation stopped, or wages were increased by federal mandate to keep up with inflation, the average American could spend their first 15 years saving money to escape to Mars, less time if there were a way to pay for your ticket in installments, or work off your debt in Martian mines.

But without significant changes in the US (fairly service-centric) economy, labor rights, taxes on the richest 1 percent, and leadership — in short, lacking a sociopolitical and economic about-face in the United States, fewer citizens in First World countries would be able to afford a ticket to Mars without finding jobs with salaries that are an order of magnitude or two greater than $60,000. Additionally, the process of installing a functioning, self-sustaining settlement is tantamount to launching a major world war from every side at once.

As for the cost of building a settlement on Mars, this would depend on the cost per ton of lifting material to the Red Planet. In 2017, Musk estimated that the price of moving material to Mars would be $140,000 per ton. That’d be $174,260 in 2023 — let’s be conservative and call it $200,000 per ton by the time Starship can start making trips to Mars. In 2017, Musk said $100 billion is a feasible figure for finalizing a settlement on Mars. Sticking with our napkin math, that’s nearly $200 billion.

Musk also gave estimates that this could be done as early as the year 2050 — but considering the many setbacks for NASA’s Artemis and SpaceX’s Starship, and geopolitical dissonance between spacefaring nations when it comes to . . . everything, this is a very idealistic estimate. Another oft-elided eventuality is how space contracts tend to emphasize a need to scale economic activity that has already been established as feasible. Once Musk proved his Falcon 9 rockets could deliver whatever we want to low-Earth orbit, SpaceX’s contracts quickly eclipsed launches operated by NASA, and any other entity or nation in the world.

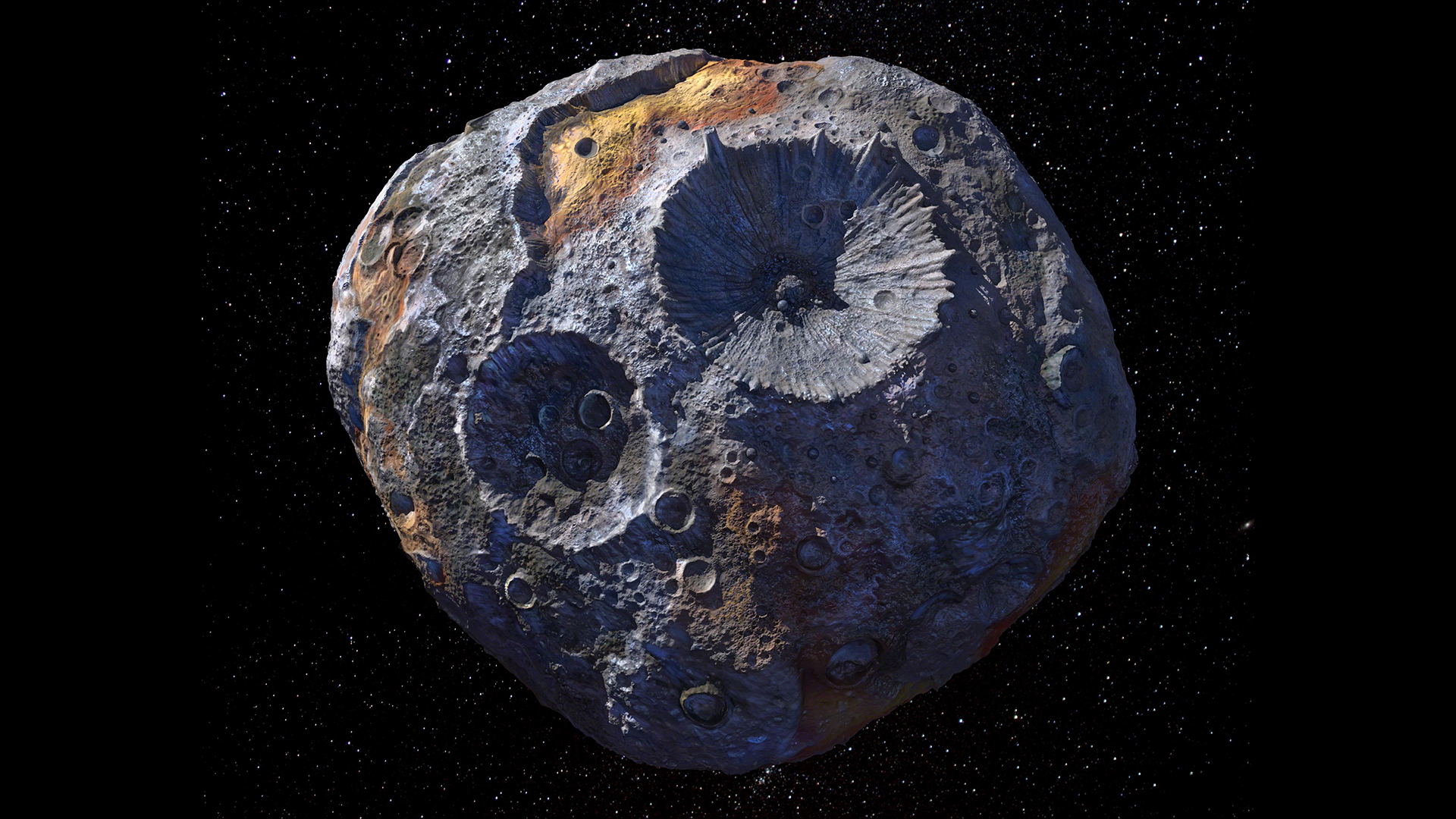

And although that money was used to spare taxpayers from footing the long bill of Starship development, the ongoing need to support and recycle crew from the ISS — not to mention SpaceX’s launch of several military assets — has contributed to economically positive horizontal growth for SpaceX. Once we get to the moon, every corporation that can afford to outbid the smaller ones will offer SpaceX, and any other private aerospace firm that can make the journey, untold riches to expand its activities on our lunar neighbor. Then there’s the riches of nearby asteroids that contain more money in rare metals than any single person on Earth has ever made or held — some of which, like Davida, 16 Psyche, Diotima, and more, hold quintillions of dollars.

In other words, no one is talking about the possible scenario where Artemis is a smashing success, where SpaceX and Blue Origin and NASA and friends are all expanding a permanent human presence on the moon, and those untold riches are being returned to Earth for the elites of the world. But despite all this success, a mission to Mars is perpetually delayed because there’s more money to be made by not going for several decades more.