From bad backs to eye strain, office work can take its toll on the body.

But it seems such perils are nothing new: researchers have found Egyptian scribes experienced damage to their hips, jaws and thumbs as a result of their efforts.

Experts studying the remains of scribes buried in the necropolis at Abusir, Egypt, between 2700 and 2180BC say that, compared with men who undertook other work, the administrators showed signs of degenerative joint changes.

“Our study should provide an answer to the question of what occupational risk factors were associated with the ‘profession’ of scribe in ancient Egypt,” said Petra Brukner Havelková, the first author of the study, at the National Museum in Prague. She added the work could also help with the identification of scribes among skeletons of individuals whose titles or profession were not known.

In the journal Scientific Reports, the team told how they analysed the remains of 69 adult males from Abusir dating to the third millennium BC, 30 of whom were known to have been scribes.

With only 1% of the population able to read and write, such men had an elevated social status and undertook crucial administrative work. Veronika Dulíková, a co-author of the study from Charles University in Prague, said scribes had been known to start working as teenagers in a professional career that may have lasted decades.

However, it seems the job might have taken a toll. While the team found small differences in the prevalence of certain skeletal traits between scribes and non-scribes, suggesting the two groups were very similar, scribes almost always had a higher incidence of certain changes.

These included osteoarthritis in the joints between the lower jaw and the skull, the right collarbone, the right shoulder, the right thumb, the right knee, and the spine – especially in the neck.

The team also found tell-tale signs of physical stress on the humerus and left hip bone, as well as depressions in the kneecaps, and changes in the right ankle.

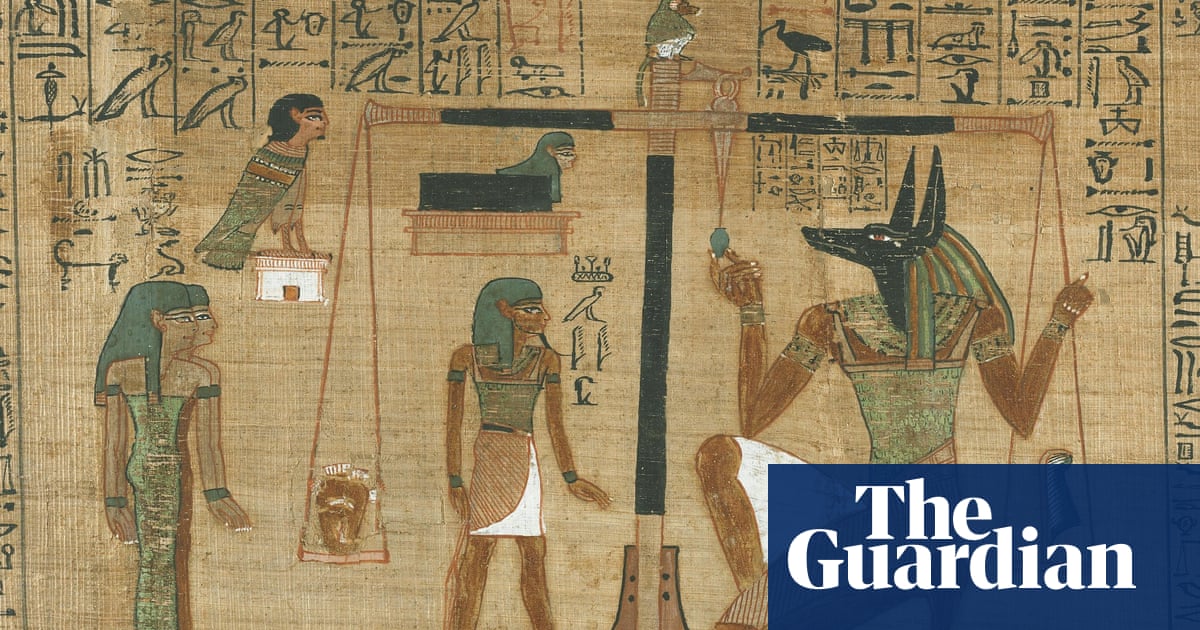

While the researchers noted some of the changes could have been influenced by some of the scribes being older at death, they said the results were consistent with the cross-legged or one-leg squatting postures scribes have been depicted adopting in ancient art, with their arms unsupported and their head forwards – a position that puts stress on the spine.

They said changes around the jaw could also be linked to such postures, or the habit of scribes to chew their rush tools to make a brush-like head. Changes in the thumb could be associated with the pinching grip scribes used to hold the pens.

Brukner Havelková said it was very likely scribes suffered from headaches at least occasionally, with evidence they also experienced jaw dislocations. “I wouldn’t be surprised if they also suffered from carpal tunnel syndrome on the hand, but unfortunately we can’t identify that on the bones,” she said.

Prof Sonia Zakrzewski, an expert in bioarchaeology from the University of Southampton, who was not involved in the research, welcomed the study.

“It’s a really nice hypothesis as we know that repeated activity leads to skeletal change and these are very plausible activities,” she said.

However, Prof Alice Roberts of the University of Birmingham said that with no comparisons in modern people, it was difficult to argue that the changes identified were really linked to activities and postures related to being a scribe.

“It has proven notoriously hard to link arthritic changes in ancient skeletons to any professions [or] activities with any degree of accuracy,” she said.