Getty Images

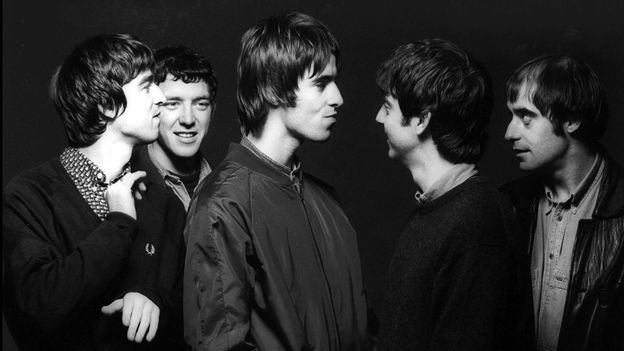

Getty ImagesThirty years after the release of their captivating debut album, Oasis have announced they are reuniting – news that has delighted middle-aged fans and a whole new generation alike.

Like all great bands, Oasis has a history that is enshrined in rock ‘n’ roll folklore: from their serendipitous spotting by record exec Alan McGee after they gatecrashed the bill of a gig in Glasgow in 1993, to the moment that marked the end 16 years later when Liam Gallagher threw a piece of fruit at his brother Noel backstage in Paris.

Warning: This article contains language that some readers may find offensive.

It’s a story that has only become more mythologised over the years as – despite persistent rumours and frequent pleas from fans – the brother Gallaghers could never quite manage to put aside their differences and get Oasis back together again. Until now. This week, almost 15 years to the day that they split up, the band confirmed they are reuniting for a string of live dates next summer. Announcing the news, they said: “The guns have fallen silent. The stars have aligned. The great wait is over.”

The huge UK and Ireland stadium tour (international dates are also believed to be on the cards) makes this one of the biggest – and certainly most-anticipated – musical comebacks in history. And it won’t just be middle-aged Gen X-ers dusting off their parkas and trying to snag tickets, but a whole new generation of fans, many of whom weren’t even born when the band first came on the scene. Oasis defined an era – but, as people of all ages unite in excitement over the news, they’ve also proved themselves to be timeless.

The reunion news comes in the same week that Oasis celebrate the 30th anniversary of their debut, Definitely Maybe. Released during the last gasps of summer 1994, just four months after their first single, Supersonic, it became the fastest selling debut album of all time in the UK, turning Liam and Noel into the rock ‘n’ roll stars they dreamed of becoming, and Oasis into the biggest UK band of a generation, who would go on to sell 75 million records worldwide.

It’s easy to look back now and see Oasis’s success as inevitable. From the start, the band stood out for their immense confidence – proclaiming early on that they would be bigger than The Beatles. Yet, for a group of working-class lads from Manchester, world domination was far from certain, something Noel recently admitted in an interview to mark Definitely Maybe’s anniversary. “A fucking singer who’s 19 and lairy, [me] writing the songs, ripping off everyone who’s fucking dead, the other three lads look like plumbers… you couldn’t invent it.”

Getty Images

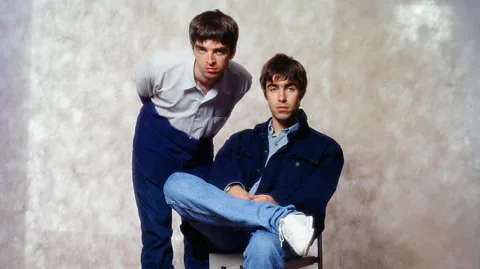

Getty ImagesBut it was their background and a burning desire to escape it that would prove to be Oasis’s superpower, connecting them to millions of others desperate to escape their everyday lives.

In the songs he wrote for Definitely Maybe, Noel captured that golden possibility of youth, when all that matters is your friends, your favourite bands and counting down the days to the weekend. The timing was fortuitous: Britain was coming out the other side of an economic recession and, with Tony Blair elected leader of the Labour Party, a switch in government was on the horizon. Change and optimism were in the air.

“In my mind my dreams are real”, sings Liam on Rock ‘N’ Roll Star, the album’s opener and statement of intent. “Tonight, I’m a rock ‘n’ roll star” – that wasn’t simply Gallagher bravado, but an invitation to anyone listening to swap the mundane for the magical, even if just for 52 minutes. “You can have it all, but how much do you want it?” asks the band on Supersonic.

Stratospheric success

Oasis emerged as British guitar music was having a resurgence, with bands like Blur, Pulp and Suede also riding high and providing an antidote to the US grunge scene that had dominated in the early 90s. But Oasis were never content being just one of many, and were unashamed in their ambition to be the biggest band in the world.

Paul Lester, editor of Record Collector, was working for weekly music paper Melody Maker at the time of Definitely Maybe’s release, and reviewed the album, describing it as “a record full of songs to live to, made by a gang of reckless northern reprobates who you can easily dream of joining.” Yet he says – despite the obvious hype for the band – it was hard to predict just how stratospheric their success would be. “Oasis were coming from another place, which was a populist place,” he tells the BBC. “They were more of a people’s band than a critic’s band. Yes, the critics absolutely frothed and raved about them, but we didn’t quite grasp how deeply these songs were going to become ingrained in the national psyche.”

The band would go on to have bigger anthem: Wonderwall, Don’t Look Back in Anger and Champagne Supernova were all still to come on their second album, (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?, but it’s the 11 songs on Definitely Maybe that really capture the spirit of Oasis.

You won’t find anyone belting out Bring It on Down at a wedding, but nothing sums up the early thrill of the band quite like a snarling Liam singing: “You’re the outcast, you’re the underclass. But you don’t care, because you’re living fast.” Noel Gallagher once called Definitely Maybe “the last great punk album in many respects… we had no effects, barely any equipment, just loads of attitude, 12 cans of Red Stripe and ambition.” If Never Mind The Bollocks was about the angst of being a teenager, then Definitely Maybe was about the glory of it, he said.

For all the Beatles-esque melodies, T-Rex-ripped riffs and Sex Pistols attitude, Noel’s influences also came from less likely places. “The good thing about Oasis is that the songs were all inclusive,” he said. “They weren’t elitist in any way. A lot of that for me came from acid house, [that] communal feeling of everyone together and that anthemic thing.”

You can feel it on Live Forever, the band’s third single and arguably their greatest song, a track whose lyrics: (“Maybe I will never be, all the things that I wanna be… I think you’re the same as me, We see things they’ll never see”) bottle that us-against-the-world feeling, when anything feels possible, even when the odds are stacked against you. Noel wrote the song in response to the Nirvana track I Hate Myself and I Want to Die. “We had fuck all, and I still thought that getting up in the morning was the greatest thing ever, because you didn’t know where you’d end up,” he said.

It wasn’t all inebriation and provocation. On songs like Slide Away the band showed their soppy side, too. There was an undeniable romanticism to Noel’s lyrics, but coupled with Liam’s raw, searing voice, often described as the perfect combination of two of rock’s most famous Johns – Lennon and Lydon – the songs became greater than the sum of their parts. “It’s the delivery and the tone of his voice… and it’s the attitude,” said Noel, reflecting on his younger brother’s charisma. “What he did was inspire the kids down the front to do something. You know if he can do it I can do it. And he’s still doing that now.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe dynamic between the two brothers was what drove Oasis to glory, and eventually into the ground. When the band parted ways in 2009, Noel said: “I simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer.” Since then the two have traded barbs in the press and on social media. Liam called Noel a “POTATO,” “a fucking stalker” and a “working-class traitor.” Noel described Liam as “a man with a fork in a world of soup.”

Noel’s recent thawing towards his younger brother was a sign that, just perhaps, a reconciliation was possible, though no-one dared believe it until the announcement came this week. With both Gallaghers having successful solo careers and each playing Oasis songs at their gigs (Liam recently completed a Definitely Maybe anniversary tour), you could also ask if we really need an Oasis reunion? Especially as, by the time the band split, they were far past their glory days.

A new generation of fans

Nostalgia is a powerful drug though, and there’s something undoubtedly thrilling about the prospect of seeing the brothers Gallagher onstage together again, especially when for years it has felt so unlikely. As Liam himself says in the announcement: “When we both come together, you have greatness.” An estimated 2.6 million applied for tickets for Oasis’s legendary Knebworth shows in 1996 (only 250,000 were successful). It’s likely far more will be scrabbling for tickets for this comeback tour. For many, it’s their first chance to see the band live. Oasis might have been on hiatus for 15 years, but their music hasn’t been, and in the interim it’s amassed a whole new generation of fans. Many have grown up listening to their parents playing Oasis records, the songs seeping into their consciousness. Others have been fed them through streaming algorithms, heard contemporary bands like Blossoms cite them as an influence or discovered #OasisCore on TikTok, where people share Oasis-inspired looks and strum the band’s tunes in their bedroom. Noel and, especially Liam, have seen their solo gigs packed with young fans.

It plays into a wider trend in which Gen Z have fallen for all things 90s. Mark Knox, who runs Brit Cult, an Instagram account dedicated to British pop culture from the 90s and early-00s, says lots of his followers are 18-24 year olds. He thinks, for a generation whose coming of age was curtailed by Covid, it’s an appealing time. “They never had their hedonistic party days and they are longing for it. So the 90s to these guys looks as radical and free as the 60s did to kids in the 90s,” he tells the BBC. A study earlier this year found that 29% of Gen Z prefer to listen to 90s music than anything from this century.

Neil Ewen, associate professor of media, communications and culture at the University of Exeter, is currently researching nostalgia for the 1990s. He thinks that the decade is seen through rose-tinted glasses – both by those who were there and those who weren’t. “We’re living in a time of perpetual crisis in the 21st Century,” he says. “Financial crisis, political crisis, climate breakdown, wars around the world… people are worried about AI. One of the reasons the 90s are seen as attractive is because we remember it as a period of relative calm. It tends to be thought of a decade of growth, of hope, moving towards the end of the century.” With the Cold War over and 9/11 still to come, there’s some truth to that, even if it overlooks the decade’s many other problems.

He also thinks it’s significant that the 90s was the last decade without social media (Noel Gallagher once described Knebworth as “the last great gathering before the birth of the internet”). “Young people, who are constantly told that they’re addicted to their phones, that nothing is real or authentic, they have a longing for the kind of connection that is romanticised when we talk about the 1990s,” says Ewen.

In an era where solo artists now dominate, a guitar band conquering not just the charts but the front pages too – especially one like Oasis – also feels like a distant memory. “Pop music has never been better… but where is the next Oasis? Rowdy, proudly working-class, making anthemic rock music. It just isn’t there,” says Knox. “I like Fontaines DC, Idles and Blossoms… but my mum can’t name any of their songs. Oasis looked like us, dressed like us, talked like us and wrote songs for us. And I don’t think anyone else ever came along after and did that again.”

For many, Oasis represent the kind of rock stars you don’t find any more. Their interviews were unfiltered, their gigs often spiralled out of control, their spats – whether with each other or their peers – were public. One 1994 interview, which descended into a raging argument between the Gallagher brothers on what was acceptable rock ‘n’ roll behaviour, was so legendary it was released as a 7in single. “They were a gift to the music press because they were so quotable,” says Paul Lester. “They’ve become this kind of exotic museum piece. You don’t get lairy bands on national TV at seven o’clock in the evening now.”

Britpop as a movement was boisterous, but its laddish-ness could also veer into sexism and misogyny. Later Oasis gigs often felt more confrontational than celebratory. It’s hard to imagine a more enlightened Gen Z readily accepting those attitudes. But on the same day the band confirm their comeback, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer warns people that things will get worse before they get better, perhaps it’s simply that feeling of sheer blind optimism and escape that people are hankering for, and that Oasis can hopefully deliver.

And for those of us who bought Definitely Maybe on the day it came out and spent hours on the phone trying to get tickets for Knebworth, an Oasis reunion offers a chance to revisit our youth, if only for a couple of hours. Because, as Noel Gallagher says: “People will never, ever forget the way that you made them feel.”