By Rachelle Krygier and Laura García, BBC Monitoring and BBC Mundo

Getty

GettyFighters belonging to breakaway groups associated with Colombia’s largest rebel movement are posting videos on TikTok to entice young people to join them.

The BBC has investigated the growth of guerrilla “recruitment” videos, with dissident factions yet to agree to a peace deal with the Colombian government.

“One or two start the trend and it becomes fashionable in the classroom,” says Lorena (not her real name), a 30-year-old teacher in Cauca, a rural region in south-western Colombia.

She says as she enters her class, she is often met by students filming themselves on their smartphones, drawing symbols inspired by the now-demobilised Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia guerrilla group (Farc) on the blackboard, or dancing to revolutionary tunes.

Lorena, who asked to remain anonymous for her own security, says this kind of pro-guerrilla behaviour has become increasingly common among pupils.

“It used to be more secretive… [but] it has become completely normalised,” she said in an interview with the BBC over Zoom.

“Sadly, it’s one or two [students] that start to see the clips [on Tiktok] in one classroom – and then it becomes trendy.”

She said students then often disappear, and the next time she sees them they are appearing in TikTok videos – armed and dressed as fighters.

In Cauca, children and adults alike have grown up alongside the Farc, which has had a strong presence in the region since the leftist armed group was created in 1964.

The group, which had over 20,000 members at its height, officially demobilised and signed a peace agreement with the government in 2016.

Yet some dissident factions have yet to lay down their weapons, and some of the most powerful of those armed units are currently active in Cauca.

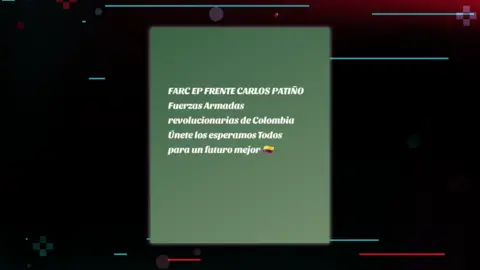

These Farc factions have joined forces to form a larger umbrella group, dubbed the Estado Mayor Central (EMC).

Authorities estimate the EMC has more than 3,000 members.

So far, attempts to negotiate with these diverse factions by the current left-wing government, led by President Gustavo Petro, have faltered.

The factions continue to operate, reportedly financing themselves through drug-trafficking and maintaining control of many rural territories.

Officials say the dissident groups continue to swell their ranks, with younger people among those being targeted for recruitment.

While the recruitment of children by guerrilla groups has been a problem in Colombia for decades, the infiltration of social media has made it more challenging to eliminate, experts and officials told the BBC.

The Colombian Ombudsman’s Office Early Alert System Delegate, Ricardo Arias Macías, told the BBC that at least 184 young people were recruited by guerrilla groups in 2023.

In 2024, in the first half of the year alone – up to June – 159 young people had enlisted – all of them under 18; 124 of them were children from Cauca.

“Those are just the reported cases – most of them don’t even get reported,” he said.

Lorena, who has been teaching in poor, remote communities for nine years, says in the past year at least 15 students from her school have left to join the guerrillas.

“You feel so much pain, disappointment… so much impotence,” she told the BBC.

According to Lorena, the guerrilla factions’ use of social media, particularly TikTok, “exploded” following the Covid pandemic.

Now, with the majority of students having phones with internet access, “we can’t control it,” she says: “They’re always on them”.

Over a period of four weeks, the BBC identified more than 50 accounts on TikTok promoting Colombian guerrillas – featuring fighters showing off their flashy lifestyle and rallying others to join.

They do not, however, dwell on the dangers of being part of an armed group.

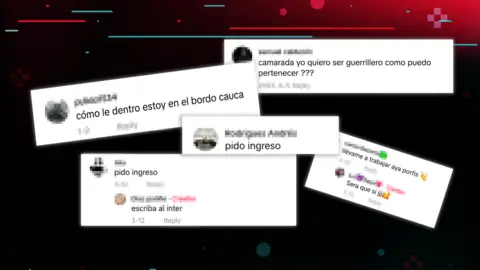

Many of the videos posted by fighters in EMC factions contained implicit recruiting language, encouraging viewers to join one faction or another. Repeatedly, users asked how to join in the comments section.

Songs extolling fallen leaders and guerrilla life provide the soundtrack to these videos, and young girls and boys are seen carrying weapons or standing beside coca crops.

While some accounts were explicit in stating the name of their faction, many alluded to Farc by using a samurai emoji with a Colombian flag.

In April, Colombia’s Defence Minister Iván Velásquez warned of the dangers of such EMC TikTok videos.

“These are recruitment actions that are being carried out to attract children – minors – in various regions of the country,” he said.

According to Santiago Rodríguez, a journalist who works for Colombian investigative site La Silla Vacia, the EMC has had official social media channels to share statements for a long time, including a WhatsApp group with journalists and a Facebook account.

But more recently the content has been migrating to TikTok – and, as such, reaching a younger demographic.

According to Sergio Saffon, Colombia expert for investigative media organisation InSight Crime, videos posted by EMC fighters are particularly effective with children living in poor communities.

Young people are sold “a great life where you can have anything you may want: money, women, motorcycles,” says Mr Saffron.

Many of the TikTok accounts that the BBC identified were eventually banned by the platform. Yet new content was constantly popping up, as other accounts were taken down.

TikTok did not reply to a written request for comment from the BBC, but their community guidelines say that “moderating millions of pieces of content each day is a complex effort, and developing a trusted process to do so is foundational”.

Countering the guerrillas’ social media drive is not simple for the Colombian authorities either.

The Ombudsman’s Office has created a new delegation specifically to tackle the issue, but it was only just getting off the ground, Mr Arias said.

Even the EMC is trying to prevent its members from grandstanding on TikTok, according to Sebastián Martínez, a member of one of the EMC’s factions in Cauca who is officially part of the group’s now-stalled dialogue commission.

“There’s no Farc propaganda campaign to recruit people through social media,” he told the BBC, in a Zoom interview.

“There are particular cases that sometimes get out of our hands… That can bring security risks, and we are trying to control it,” he said.

Mr Martínez conceded that the EMC’s financing came from illegal businesses, such as taxes on coca, poppy, and marijuana growers – though he claimed they were now venturing into legal agricultural crops as well.

He also admitted that the group was enlisting children as young as 15 years old, which Colombian authorities view as forced recruitment due to what is described as a “lack of agency” at that age.

Meanwhile, Lorena is struggling to save her students from the perils of guerrilla life.

She and a group of other teachers created a school network to monitor social media accounts, and set up an emergency chat for students to reach out when they feel at risk.

“We can’t give them everything. We fight tooth-and-nail, and try to ignore our fears.

“But when you see one life change – when they come back and tell you they’ve graduated college or started a business, that’s what keeps you fighting.”

Additional reporting by Jonathan Griffin, BBC Trending