Let’s begin with a brief recap of the current state of play at Intel. For starters, despite bold promises to regain technology leadership, it remains miles behind TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited) in chip manufacturing and indeed is increasingly relying on TSMC to manufacture its latest and future CPUs, such as Meteor lake, Lunar Lake and Arrow Lake.

Meanwhile, it’s losing market share to AMD in server CPUs, Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X Arm-based chips are a real threat in Intel’s largest consumer market, laptops, Intel’s Arc graphics effort has been a bit of a flop so far, and now its last two generations of desktop CPUs are badly broken.

Most recently, Intel announced some very poor financial results and decided it needed to fire another 15,000 employees after already trimming 5% of its workforce last year, a move that CEO Pat Gelsinger branded “some of the most consequential changes in our company’s history.”

That’s just the Cliff notes. There are several other lesser horror stories, like reigning in plans to build fabs in Europe and the fact that things are so bad Intel cancelled dividend payments to shareholders. But an obvious question follows. How did Intel get it all so wrong?

Arguably, you could say the rot set in when Paul Otellini replaced Craig Barrett as CEO way back in 2005. Barrett had a PhD in materials science from Stanford. Otellini was an economics grad with an MBA. Put simply, sales replaced engineering at the top of Intel.

Admittedly, Intel’s next CEO Brian Krzanich was from the engineering side, but let’s not allow details like that to get in the way of an easy narrative. The story goes that Intel got lazy and cynical under sales and marketing-driven leadership, leaned into its near monopoly status in the x86 market, and it was all downhill from there.

More specifically, the most obvious indication of Intel in decline were its troubles with the 10nm node. Originally scheduled to go into production in 2016, Intel first conceded that the node would be delayed in mid 2015.

Strictly speaking, Intel released a small number of dual-core Cannonlake CPUs on 10nm in 2018. But it wasn’t until the Ice Lake mobile CPU launched in late 2019 that 10nm really went live. Arguably, it wasn’t until 2020 that Ice Lake laptops were available in volume.

In the cutting-edge chip industry, that’s a catastrophic delay. Indeed, if you consider the Intel chips you can buy in PCs today, the picture barely gets any better. Those broken 13th and 14th Gen desktop CPUs are on the Intel 7 node, which is a rebrand and revision of the 10nm technology that was meant to go on sale nearly 10 years ago.

While you can get Intel 4 silicon in Meteor Lake laptop CPUs, it’s a chiplet design with only the CPU tile made on Intel silicon. All the other functional chiplets, which are the majority of the overall processor, are made by TSMC.

Oh, and Intel has conceded that even with just the titchy CPU tile made on Intel 4, it has been struggling to ramp up production. Sales of Meteor Lake laptops have been limited by processor production volume and the latest rumours claim that this problem is ongoing today.

Whatever, it is certainly true that both of the active tiles for Lunar Lake, Intel’s next-gen mobile CPU, will be produced by TSMC, not Intel. Only the passive base tile, which is basically a glorified PCB with wiring, is on Intel silicon.

It’s not totally clear how Intel’s next-gen Arrow Lake desktop chips will be made. But they’re definitely chiplet designs and rumours suggest that most models will have all-TSMC silicon for the active tiles, with perhaps a few low-end SKUs using Intel silicon for a single active tile.

In other words, Intel continues to increase the TSMC content in its chips, including for chips that have yet to go on sale. We’re still years away from Intel being able to reverse that placeholder strategy of farming out production because its own production nodes aren’t good enough.

It’s worth dwelling on that for a moment. He we are in 2024 and Intel is increasing the proportion of its production at TSMC for future processors because its own nodes aren’t good enough.

Further evidence for how far Intel is from truly turning the ship came in the form of a roadmap produced by Intel Foundry Services or IFS. That’s the business unit Intel has separated off composed of its fabs or chip factories.

Intel hopes to move from largely using its fabs to produce its own chips to also being a major contract manufacturer of chips for customers. It’s in that new role as a customer fab that it hopes to not only make better chips of its own, but also take on TSMC directly.

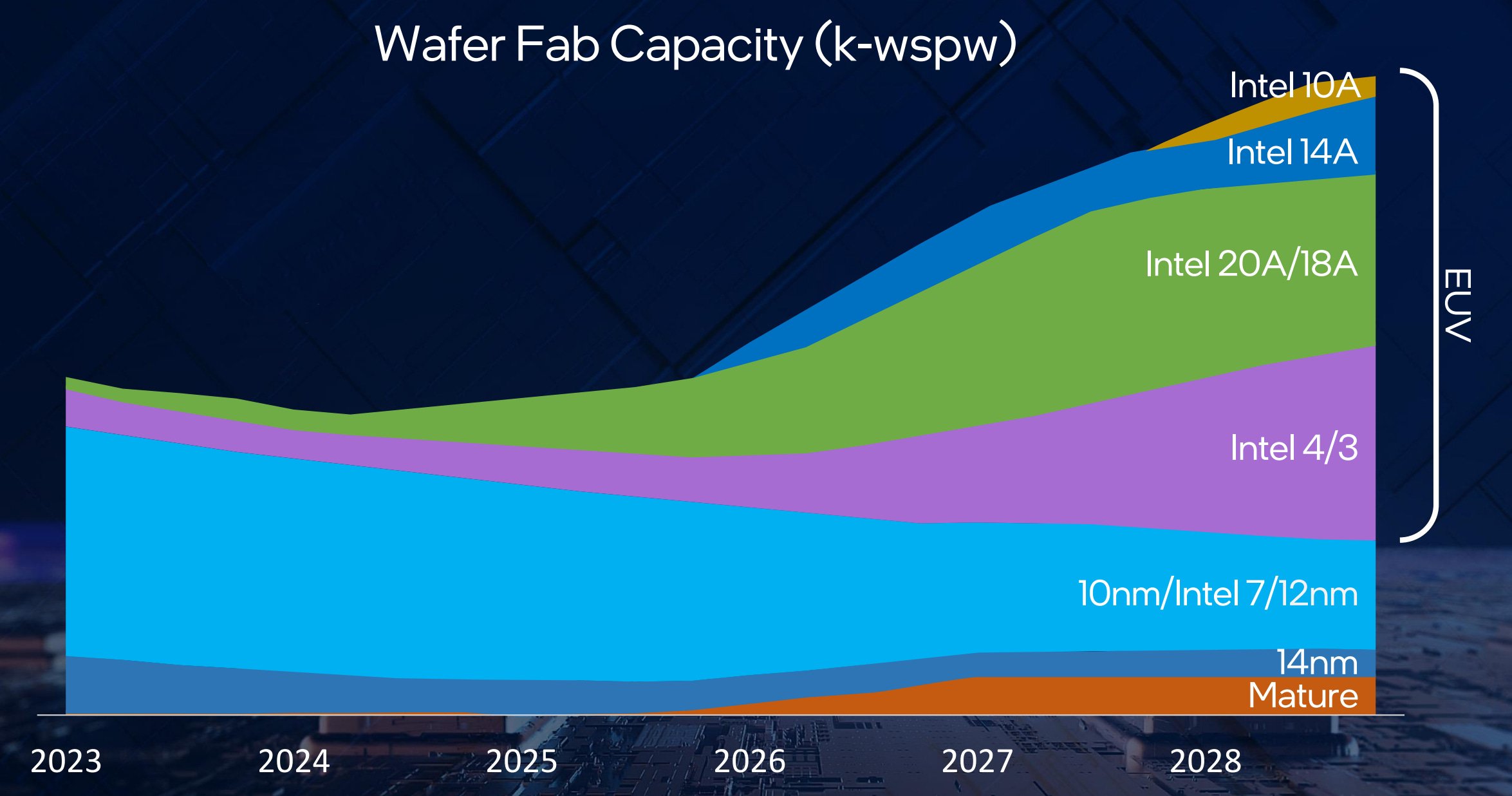

So, here’s the thing. Going by IFS’s own figures, which are presumably more optimistic than pessimistic, the majority of Intel’s production capacity won’t be on nodes as or more advanced as Intel 4 until 2027. Even in 2026, Intel capacity will be around 65% composed of 10nm-class nodes, now branded Intel 7, or older.

Moreover, if the rumours that Intel 4 yields are still problematic, what are the odds that its upcoming 20A and 18A nodes are going to be zingers from day one? When you put it altogether, it’s clear that whatever Intel is claiming for its bold strategy of introducing five new nodes in four years, the company is still a long way from recovery.

Indeed, when you factor in the debacle with 13th and 14th Gen Raptor Lake desktop CPUs, rumours of continued problems with Meteor Lake supply and Intel latest financials and belt tightening, it’s hard to see how things aren’t continuing to get worse.

That’s particularly disheartening in the context of the arrival of Intel’s latest CEO, Pat Gelsiginer, in 2021. Gelsinger is supposed to be one of the good guys, an Intel engineer who was forced out of the company during its marketing-skewed days, who then returned to right the ship.

At last, there was an engineer back at the helm. But as the years tick by, Gelsinger’s appointment looks less and less like a case study in how leadership can save a faltering giant and more like proof there’s only so much one man can do.

Obviously Intel is far from done. It’s still a huge company with massive resources. Who’s to say that two years from now it won’t have some stellar CPUs on the market, plus perhaps a third generation of Arc graphics cards taking the fight to Nvidia and AMD.

On that latter note, it would be a massive shame if Intel Arc graphics become a casualty of Intel’s need to save costs any time soon. The PC gaming graphics market desperately needs more competition and a healthy Intel would be good for all of us.

The same goes for CPUs, but perhaps to a lesser extent. In the long run, it’s hard to imagine that the PC won’t eventually be assimilated by the ARM architecture. Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X chip looks like the first genuine step in that direction. And if it does happen, if Arm does take over the PC, there could be all kinds of competition. Along with Qualcomm, we could see Mediatek, Nvidia and indeed AMD and even Intel making Arm-based CPUs for PCs.

If that’s somewhat speculative, what’s clear in the here and now is that Intel needs to get its act together and fast. The first thing it should do is provide far better clarity over the status of those borked Raptor Lake processors. Yes, it has now announced a two-year warranty extension, but there’s still a lack of clarity hanging over the whole affair.

After that, well, it really could do with sorting out those fabs. But that’s looking like a far, far taller order.