Figure 1. Feeding frenzy: The world’s largest fish, a slow-moving whale shark, feeds on snipefish herded into bait balls by agile tuna in the Azores. Attribution: Jorge Fontes

The competition highlights the wonders of the natural world, celebrating researchers working to understand its mysteries. BMC Ecology and Evolution and BMC Zoology invited anyone affiliated with a research institution to submit to one of the following four categories: ‘Research in Action’, ‘Relationships in nature’, ‘Protecting our planet’, and ‘Life close-up’.

Our Senior Editorial Board Members lent their expertise to judge the submissions, selecting the overall winner, best image, and runner-up from each category. The board members assessed the scientific stories behind the photos and their artistic merit.

Please enjoy viewing our winning images and discovering the stories behind the camera.

Overall winner

Figure 1. Feeding frenzy: The world’s largest fish, a slow-moving whale shark, feeds on snipefish herded into bait balls by agile tuna in the Azores. Attribution: Jorge Fontes

Marine biologist Jorge Fontes captured the winning photograph. Jorge works at Okeanos-UAc, Institute of Marine Sciences, and is involved in a project to study the impact of fishing on the largest animals in the oceans. “The world’s largest fish, the whale shark, is a gentle giant found in warm tropical and subtropical waters globally,” explains Fontes. “It likes to eat plankton, which it filters through its wide mouth. During warm summers, many adult whale sharks gather near the Azores. However, because these waters are not very productive in the summer, there isn’t much plankton for them to eat. Instead, the slow-moving whale sharks feed on snipefish, herded into tight groups at the surface by large schools of speedy bluefin and smaller tropical tunas, leading to a feeding frenzy. With the baitfish gathered together, the whale sharks use powerful suction to fill their huge mouths with food. This feeding partnership between sharks and tunas is rare elsewhere but common in these islands when both are present. To better understand this unique behaviour and the impact of local tuna fisheries, we have tagged whale sharks with advanced trackers (equipped with accelerometers, cameras, and sensors to measure location, pressure, and temperature)”.

Research in action: best in category

Figure 2. A Few Drops of Medicine: An ornithologist feeds a critically endangered Kiwikiu electrolytes and protein to prepare it for its journey to the Maui Bird Conservation Center. Attribution: Ryan Wagner

Ryan Wagner, a conservation biologist in the School of Biological Sciences at Washington State University, won best in category for “Research in action”. “A single mosquito bite can kill a Kiwikiu, one of the most endangered birds in the world, with only 130 remaining. Following the introduction of mosquitoes in the 1800s, which carry deadly avian malaria, native Maui birds have found refuge on the high, cold slopes of the Haleakala volcano. However, as climate change warms the islands, mosquitoes have reached previously inaccessible elevations, killing birds. In 2024, the Maui Forest Birds Recovery Project (MFBRP) made the difficult decision to catch several pairs of Kiwikiu to create a captive population. As shown in the photo, medicine administered by ornithologists provides a boost of electrolytes and protein to strengthen the bird for a quick helicopter flight to the Maui Bird Conservation Center. There, it will be treated for malaria and join a captive breeding program to help save the species from extinction”, explains Ryan.

Research in action: runner-up

Figure 3. Restoration of the Everglades: A postdoctoral researcher investigates the role fauna play in phosphorus dynamics. Attribution: Brandon Güell

The runner-up of the ‘Research in action’ category was Brandon Güell, a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Florida International University. High phosphorus levels from agricultural and stormwater runoff is harming the Everglades’ unique wildlife by affecting plant diversity and triggering algae blooms. To address this issue, the state and federal governments are funding the largest ecosystem restoration project in the world. Here Güell’s colleague, Dr. Janelle Goeke, is conducting research to understand the role of fauna in phosphorus dynamics and exploring the potential of managing fish populations as a restoration tool.

Relationships in nature: best in category

Figure 4. Chasing the fish: An Arctic Skua mimics the flight of a Black-legged Kittiwake to steal its fish. Attribution: Alwin Hardenbol

The winner of the ‘Relationships in nature’ category captured an Arctic Skua mimicking the flight pattern of a Black-legged Kittiwake in an attempt to steal it’s fish. The photo was submitted by Alwin Hardenbol, a postdoctoral researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Alwin comments, “This behavior, where one animal deliberately takes food from another, was observed from a boat near Vardö, Norway. Arctic Skuas often exhibit this type of behavior, known as kleptoparasitism, in large numbers. While in Norway, I observed Humpback whales bringing fish to the surface, which the Kittiwakes and other gulls caught. The Skuas then attempted to steal the fish from them. All of the Skuas’ attempts I observed were successful, demonstrating their efficiency in this relationship.”

Relationships in nature: runner-up

Figure 5. Sleeping on red velvet: A plant-pollinator interaction between a Helen’s Bee orchid and two Eucerini bees.

Martha Charitonidou, a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Ioannina, submitted the runner-up for this category. “Unlike the majority of Ophrys orchids, which produce flowers imitating female insects, Helen’s Bee orchid is the only species in this genus known to use shelter mimicry as its pollination strategy,” Charitonidou explains. “Helen’s Bee orchid is one of the most easily recognizable members of the genus Ophrys due to its large flowers with a specialised, burgundy-coloured petal (labellum), which in the bee visible spectrum looks like a black hole on the ground that a bee would use to seek shelter. As shown in this photo, male Eucerini bees can be seen crawling into Helen Bee orchid flowers in search of shelter during early morning or late evening hours.”

Protecting our planet: best in category

Figure 6: Coral health monitoring at the Great Barrier Reef: A park ranger assesses coral health at Lady Musgrave Reef in the southern Great Barrier Reef. Attribution: Victor Huertas

Victor Huertas, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at James Cook University in Australia, captured the winning image for ‘Protecting our planet’. The photo captures a park ranger assessing coral health at Lady Musgrave Reef in the southern Great Barrier Reef. Corals bleach when stressed, causing them to expel the colourful photosynthetic algae that live inside them and supply them with nutrients. The Australian government’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority recently reported that this summer the UNESCO World Heritage-listed reef system has experienced widespread coral bleaching, the fifth mass bleaching episode in the Great Barrier Reef since 2016. Victor explains, “Equipped with a slate and data sheets, the ranger examines coral colonies, documenting their condition. Monitoring coral health is important for understanding and preserving this delicate ecosystem. The vibrant reef and the marine life it harbours emphasise the beauty and ecological significance of the Great Barrier Reef and the need for ongoing conservation efforts.”

Protecting our planet: runner-up

Figure 7. Conservation of the Bonelli’s eagle: A GPS transponder allows researchers to identify the power lines a Bonelli’s eagle had visited before her death.

Roberto García-Roa, an evolutionary biologist and conservation photographer affiliated with the University of Lund in Sweden, submitted the runner-up for ‘Protecting our planet’. The photo tells the story of “Bruma”, a Bonelli’s eagle who sadly died from electrocution caused by a power line. García-Roa says, “The Bonelli’s eagle population is declining, and they are now considered endangered in the European Union. GPS transponders track the eagles’ movements, helping researchers identify high-mortality areas associated with power lines. In the image, Bruma, who was tagged with a GPS transmitter, lies lifeless after being electrocuted. Information collected by the tracker enabled scientists and authorities to identify the power lines Bruma had visited before her death. This information is crucial for modifying the power lines to prevent other animals from suffering the same fate. Such measures are critical, as thousands of birds die from electrocution in Europe every year.”

Life close-up: best in category

Figure 8. A concerned freeloader: A non-pollinating fig wasp uses its specialised ovipositor to deposit eggs inside a fig. Attribution: Abhijeet Bayani

Dr Abhijeet Bayani, a biologist from the Indian Institute of Science, captured the winning image for the ‘Life close-up’ category. Fig trees, crucial in tropical ecosystems as they provide food for many animals throughout the year, have evolved to have flowers inside their fruit. The only way a fig can be pollinated is with the help of minuscule fig wasps, which burrow inside and lay their eggs within. The relationship between figs and fig wasps is highly interdependent – both rely on each other to complete their life cycles, making it a classic example of co-evolution. The female wasps enter the fig, lay eggs, pollinate it and eventually die within the fig. Once the eggs hatch, the male wasps mate with the newly hatched female wasps and create an exit tunnel for the females to leave and locate new figs. Some fig wasps are essential for pollinating the figs, while others, like the non-pollinating wasp captured in Dr Abhijeet Bayani’s winning photo, have evolved a specialised ovipositor to cheat the fig, which is used to bore through the surface of the fruit from the outside and deposit eggs inside. Their offspring then develop inside the safety of the fig, seemingly without benefiting the fig tree itself.

Life close-up: runner-up

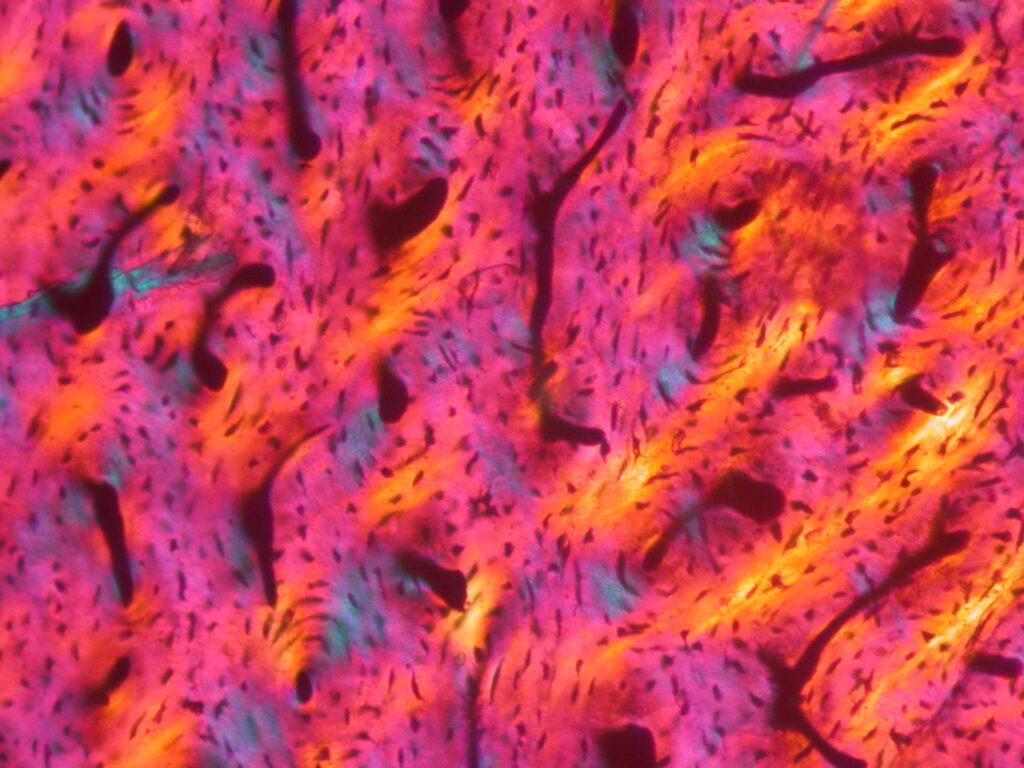

Figure 9. Inside a dinosaur bone: Unlocking the life history of Megapnosaurus. Attribution: Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan

Professor Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, a palaeontologist from the University of Cape Town, submitted the runner-up for ‘Life close-up’. Using a microscope, Chinsamy-Turan demonstrates how fossilised bones can provide valuable information about long-extinct species. Chinsamy-Turan explains, “When viewed under a petrographic microscope, this image of a thin section of a femur of Megapnosaurus, a predatory dinosaur from Southern Africa, reveals important information about the biology of this ~190-million-year-old animal. The large black areas once contained blood vessels, nerves, and other connective tissue, while the smaller black specks are the spaces in which bone cells were once located. After death, organic tissue decomposes, and the empty spaces are infilled with sediment and minerals. The vibrant colours visible in the image provide insight into the organisation of the apatite, which is the mineral component of bone that survives fossilisation. In life, collagen and apatite are intimately associated, and although collagen is no longer present, the overall arrangement of the apatite suggests that the bone was deposited rapidly.” Studying the microstructure of fossilised bone can provide valuable insight into the life history of dinosaurs and other extinct vertebrates. This can include details about the sex, growth rate, presence of disease, and the potential impact of environmental factors on the growth of the extinct animal.

Many congratulations to all of our winners!

All the figures have been released under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), so everyone is welcome and encouraged to share them freely, as long as you clearly attribute the image to the author. To learn more about the competition and the winning images, please read our accompanying editorial.