Joe Biden unveiled plans for sweeping US Supreme Court reforms, as he seeks to cement his legacy in the twilight of his presidency despite Republicans branding the proposals dead on arrival.

Stung by shock rulings on abortion and other topics and by a series of scandals involving the conservative-dominated court, Mr Biden called for 18-year term limits for justices and an enforceable ethics code.

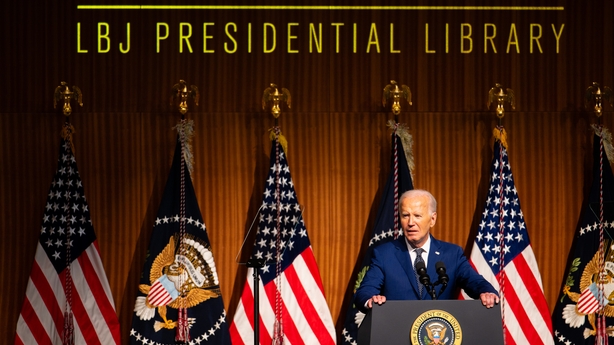

“Extremism is undermining public confidence in the court’s decisions,” Mr Biden said in a speech outlining the “bold” plans at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, Texas.

Making his first speech on the road since dropping out of the 2024 election, Mr Biden also proposed a constitutional amendment to reverse the Supreme Court’s recent ruling backing Donald Trump’s claims of presidential immunity.

“There are no kings in America,” he said at the library – which celebrates the legacy of President Johnson, or LBJ, the last incumbent US president not to seek a second term back in 1968.

Mr Biden’s move follows a series of shock Supreme Court decisions, especially the 2022 repeal of the nationwide right to abortion, an issue which has become crucial in November’s election.

Vice President Kamala Harris, now the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, said in a statement that she and Mr Biden both called on Congress to support the plans.

“These popular reforms will help to restore confidence in the court, strengthen our democracy, and ensure no one is above the law,” she said.

However, Mr Biden’s proposals have almost no hope of getting through a deeply divided US Congress, with Republicans holding a majority in the House of Representatives.

Republican Speaker Mike Johnson said in a statement that the “dangerous gambit of the Biden-Harris administration is dead on arrival in the House.”

Mr Biden however retorted in his speech that Mr Johnson’s “thinking is dead on arrival.”

Close to zero

The plans would see justices serve terms of 18 years with new justice appointed every two years. The ethics code would meanwhile force judges to declare gifts and possible conflicts of interest.

The US Supreme Court plays an outsize role in determining the lives of ordinary Americans, with justices appointed for life deciding on almost every key issue from reproductive health to the environment.

It currently has a 6-3 conservative majority, including three right-leaning justices appointed by Mr Trump while he was president.

However, public opinion has recently turned against an institution once seen as the last impartial arm of the US government, with a recent poll showing nearly two-thirds of Americans believe that the court’s decisions are mainly political.

As well as the abortion judgement, the court has also rolled back the power of federal agencies and blocked Mr Biden’s signature student debt forgiveness plan.

It then partially ruled in early July in favour of Mr Trump’s claims that he had immunity from prosecution for acts committed while president.

Mr Trump is now using that ruling to challenge his recent criminal conviction in an adult film star hush-money case and a series of other prosecutions.

Meanwhile the Supreme Court has been rocked by ethics scandals involving arch-conservative justices.

Justice Clarence Thomas recently admitted that two luxury vacations he took in 2019 were paid for by a billionaire Republican political donor.

Mr Thomas, the longest-service justice on the court, has also ignored calls to recuse himself from cases related to the 2020 election, after his wife took part in the drive to keep Mr Trump in power despite his electoral loss.

Justice Samuel Alito has also rejected calls to recuse himself from some Mr Trump-related cases after flags linked to the former president’s false election fraud claims were discovered to have been flown outside his home and vacation property.

Legal expert Steven Schwinn warned that Mr Biden had a “close to zero” chance of getting the plan through Congress.

However, Mr Biden was probably trying to “raise public consciousness” and “introduce the Supreme Court as an election issue,” Mr Schwinn, a law professor at the University of Illinois Chicago, told AFP.