Those lucky few Aussie greasers who saw Bon Scott’s first ever performance with AC/DC in September 1974 witnessed a rock’n’roll rebirth, its nerves comprehensively drowned, anaesthetised and powdered.

“Bon downed about two bottles of bourbon with dope, coke, speed, and said ‘Right, I’m ready,’” guitarist Angus Young was quoted in music journalist Clinton Walker’s biography of Scott, Highway to Hell, recalling his chaotic try-out gig at the Poorkara Hotel in Adelaide. “There was this immediate transformation, and he was running around with his wife’s knickers on, yelling at the audience. It was a magic moment. He said it made him feel young again.”

A few weeks later, Scott was inducted as a full-time member of the band ahead of his official debut at Rockdale’s Masonic Hall on 5 October, 50 years ago this week. Neither his life, nor rock music itself, would ever be the same again.

With Scott’s bawdy, funny and chant-worthy lyrics lashed to Malcolm and Angus’s visceral boogie rock riffs, AC/DC found the formula that would carry them to the highest echelons of rock stardom. Classics such as “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock’n’Roll)”, “T.N.T.” and “Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap” paved the on-ramp to 1979’s Highway to Hell and its multiplatinum international success.

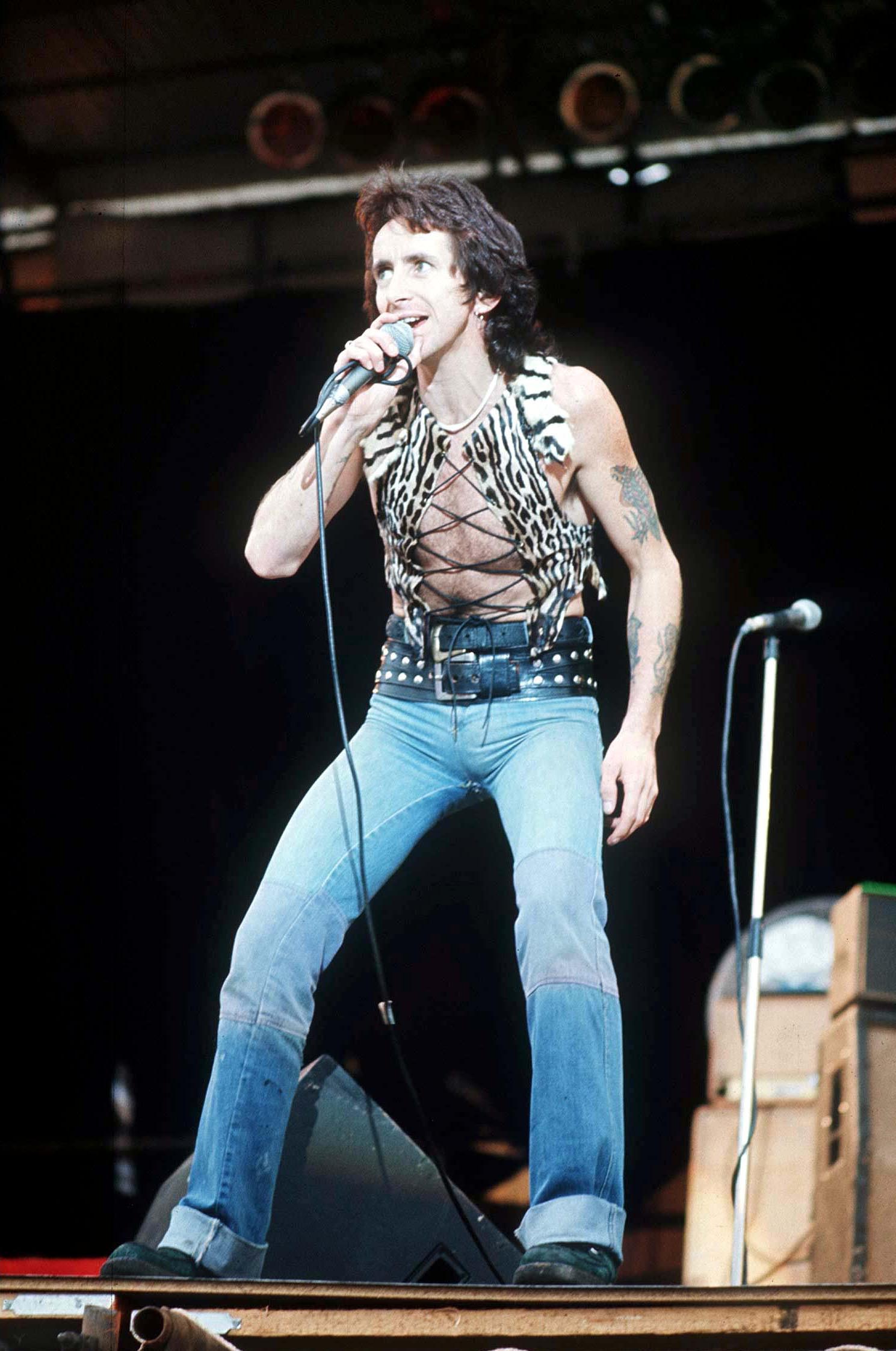

With his skintight T-shirts, ripped denim jackets, tattoos and attitude – outwardly at least – of brutish abandon, Scott epitomised the ragged rebellion at the root of the fun, dumb and dangerous-to-know hard rock music that AC/DC pioneered in the Seventies.

Sexy enough for the girls, tough enough for the bikers, he was an icon of larrikin living – roaring about sex, booze and rock’n’roll directly from the gutter. His piercing squeals and lock-up-your-daughters lyricism, often delivered with a lascivious smirk, became the definitive blueprint of what a rock lead singer should be for the coming decades.

Sadly, he’d also come to define rock’n’roll’s most classic trajectory of addiction and tragedy. It was in tribute to Scott, who died aged 33 from alcohol poisoning just six years later in February 1980, that Back in Black (released that year) became the second best-selling album of all time, behind only Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

At the time of his first appearance, this 28-year-old tearaway – born in Scotland but resident of Australia from the age of six – had already done a deal or two with death, become accustomed to the bitter sting of failure, and was ready to throw life to the four winds. His two previous bands, Sixties bubblegum popsters The Valentines and prog rockers Fraternity, had both fizzled out, landing him back in Adelaide with his rock dreams in tatters and facing the prospect of loading trucks at a local fertiliser plant to get by.

His 1972 marriage to office worker Irene Thornton was dissolving amid his emotional distance, hard drinking and drug habits that had earned him the nickname Road-Test Ronnie. After one major row, and copious Jack Daniel’s at a rehearsal with his latest local band The Mount Lofty Rangers, he jumped on his Suzuki motorbike and crashed himself into a three-day coma.

Lost, damaged and doing odd jobs for his former Valentine’s co-singer Vince Lovegrove, Scott had little left to lose. So, when in August 1974 Lovegrove urged him to catch a nascent Sydney rock’n’roll band called AC/DC at the Pooraka Hotel, knowing they were looking to replace their peacocking singer Dave Evans, Scott stopped by and was knocked out by what he saw.

“There’s this little guy in a school uniform [Angus], going crazy, and I laughed,” he told the documentary film Let There Be Rock. Backstage, according to Lovegrove, the long-in-the-broken-tooth singer faced off against cocky young upstarts Malcolm and Angus Young. “You reckon you can rock the arse off us?” Angus baited him. “You young kids? You bet,” Scott replied.

One rehearsal-cum-audition later and Scott was officially in. Thanks to a chameleonic ability to adjust to whichever sort of band he was fronting, his prowling onstage magnetism and impish menace slotted into AC/DC like a motorised wrench around a Harley Davidson wheel nut.

In her 2014 book My Bon Scott, his wife Thornton recalled his enthusiasm for his new role. “AC/DC played this loud, unapologetic rock that nearly blew your head off, and Bon’s voice just clicked right into it,” she wrote. “Bon looked genuinely, deeply happy, for the first time in a long time.”

“He was on about the third roll of the dice,” Walker tells The Independent, “it’s death or glory to a certain extent.” In his short but legendary tenure with the band, Scott would race on to both. His addition to AC/DC was fundamental in creating the band’s tone and image, which spoke to – or rather growled slyly in the ear of – the hedonistic everyday rock fan.

“Bon was this working-class tearaway kid,” says Walker. “That larrikin streak was a really romantic, antihero kind of thing, but also, he was a completely and utterly compelling performer [and] so cheeky. He was just mischievous, and you were never exactly sure if he was putting it on a bit. It was always with a bit of a wink and a tickle, like a bit of old-world vaudeville.”

“I’ve always thought of him as a Fagin-like character,” says Jesse Fink, author of Scott biography Bon: The Last Highway, which is released in paperback this week. “He had that edginess and sense of menace and hardness that I think they lacked with [former lead singer] Dave Evans.”

And while Scott’s lyrics were renowned for their punchy, ribald simplicity – dumbed down by the Youngs when he got too clever – Walker sees deeper meaning in his words, far beyond those tawdry double entendres.

“‘Jailbreak’ could be construed as autobiographical [Scott spent time in juvenile prison as a teenager for charges including ‘unlawful carnal knowledge’], but I construe it as part of Australia’s national biography, being a former penal colony,” he argues. And with lyrics including “I’m bleary-eyed and you’re waitin’ for the sunshine to come and kill me”, he considers “Carry Me Home”, a B-side to 1977 single “Dog Eat Dog”, to be an obscure song that prophesied his demise. “When Malcolm and Angus had the riff and Bon had the lyric and they’d work around the focal point of a chorus title tag,” he says, “that was such a great combination.”

Even on tracks that might be considered beyond the pale in 2024, such as the 1977 hit “Whole Lotta Rosie” – detailing Scott’s energetic, real-life motel encounter with a proudly plus-sized groupie – his hip-thrusting charm exonerates him. “It’s just a big lark,” says Walker. “Everybody seemed to be having a good time as far as I can tell. It’s totally affectionate. A lot of those songs are a bit loose, but it’s never mean-spirited, it’s always funny and joyous.”

The outward perception of Scott is that of a classic rock wild man tearing down the highway to hell with no brakes. “He was certainly a prodigious drinker and habitual user of drugs, which got him in the end,” says Fink. Contrastingly, Walker’s book depicts Scott as a hedonist who became increasingly hungry for more drink, drugs and sex the bigger the band got. “Bon was just outrageous, and he liked to be the life of the party, and had a magnetism,” he says. “You’re not going to slow down, you’re not gonna stop doing it.”

As with many alcoholics, Scott’s behaviour often tipped over into the boorish. He developed an ultra-crude interview persona, boasted of lining up 10 naked women at once in hotel rooms for sex, and, according to his mid-Seventies lover Silver Smith, could not maintain a relationship due to his unpredictability. “She described his tendency to basically f*** up at the most inappropriate times,” Fink says, “say the wrong thing, get out of control, drink too much, embarrass her and himself in front of family.”

Yet Fink paints Scott as a far more complex, deeply conflicted character – drinking heavily so as to overcome insecurities of class, education, and upbringing, or to gain the confidence to get onstage at all.

He had a very different life outside of the band… I felt like he was playing a role that he couldn’t get out of

Biographer Jesse Fink

“They deliberately tried to be as smutty and horrible as they could in interviews,” Fink says. Much of it was an attempt to out-punk The Sex Pistols – whom AC/DC often laid into with a Gallagher-esque fury for attention. “I don’t necessarily think that that was the real Bon in any way, shape, or form. He was actually quite an intellectual person. He read some very serious books, and he was listening to Steely Dan. He had a very different life outside of the band. He wasn’t destroying hotel rooms… he wasn’t a complete wastoid. I felt like he was playing a role that he couldn’t get out of.”

Scott’s lover, Smith, suggested to Fink that his constant drinking might have been the result of a deep-seated childhood regret. “His grandparents had come out to Australia at one point, and he was actually incarcerated at the time, and he never got to see them again,” Fink says. “This was something that he’d carried through his life and been deeply remorseful [about].”

Fink claims that Scott became increasingly dislocated from the band as their Seventies success grew, driven apart by his drunkenness and dissatisfactions; his yearning to settle down off the road and explore other creative avenues. “He had had enough,” Fink says. “He was tired of the relentless grind; his health wasn’t good. He had a developing drug habit. He hadn’t seen any money, certainly not until Highway to Hell had done very well. And I think he was looking to do other things beyond AC/DC […] He was looking at other options.”

Options he had little time to explore. On 18 February 1980, after a night out at the Music Machine club (now Koko) in Camden, the singer was left to sleep in the car of musician and alleged heroin dealer Alistair Kinnear after passing out. He was found dead the next morning.

In his book, Fink alludes to a long-running heroin connection – and two covered-up overdoses prior to his death – which the band has never admitted to. “His death in the back of a car in London in 1980 wasn’t an isolated thing,” Fink says. “He had taken a road to that point. It was a journey. [AC/DC] were constantly travelling, the amount of pressure that those guys must have been under [was] immense. I think he was dealing with a lot of his problems through his drinking, with rampant womanising and with increasing drug use.”

Fink feels that Scott simply ended up hanging out with the wrong people in his later years. “By the time that he got to London in early 1980 and fell in with the heroin crowd, he was ripe for basically going down.”

The coroner’s report found no heroin in Scott’s system and recorded his cause of death as alcohol poisoning. AC/DC have always denied the overdose theory. But Fink claims to have seen emails and conducted interviews which confirm the story. “Just this year I was put in touch with a woman who’s in the new book, who actually says that Alistair Kinnear came to her house right after Bon had died and admitted that he gave Bon the heroin that killed him,” he says. “This whole thing that Bon had nothing to do with heroin is just preposterous. The evidence is there.”

Walker agrees that Scott was surrounded by heroin in his final years but doesn’t believe he was a habitual user. “He had liver damage and he was on the road and just a bit shagged,” he says. “There are people who can exist in those circles without taking the stuff. It can and does happen. He drank himself to death though, there’s no doubt about that.”

The power of the AC/DC logo is basically the mythology of Bon Scott, of living life on your own terms, living for today, and not thinking about tomorrow

The Last Highway also asserts that Scott’s legacy is broader than we think; that he wrote lyrics for Back in Black for which he was not credited. “Silver said to me that Bon finished the lyrics for Back in Black the night that he died, and that was why he wanted to go out and celebrate,” Fink says.

While that remains contested, what is without doubt is Scott’s place as a defining icon of rock’n’roll anti-conformity. Fink lauds the songs from his era with the band as the bulk of their greatest material, and Scott himself as the lightning rod of hard rock’s sizzling electricity.

“The power of the AC/DC logo is basically the mythology of Bon Scott, of living life on your own terms, living for today and not thinking about tomorrow,” he says. “That’s really the ethos of Bon Scott. He’s like the archetypal rebel… Were it not for his lifestyle, his womanising, drinking and drugging, and the image that he created for himself with that band, I don’t think AC/DC would be what it is today.”

Scott’s dirty deeds ultimately came at great cost, but no one drove hell’s highway faster.