I’m paying £361 to stand in my local park.

After six hours doing battle with Ticketmaster, including spending several hours in the queue for the queue, I had about 90 seconds to put a price on my love for Oasis.

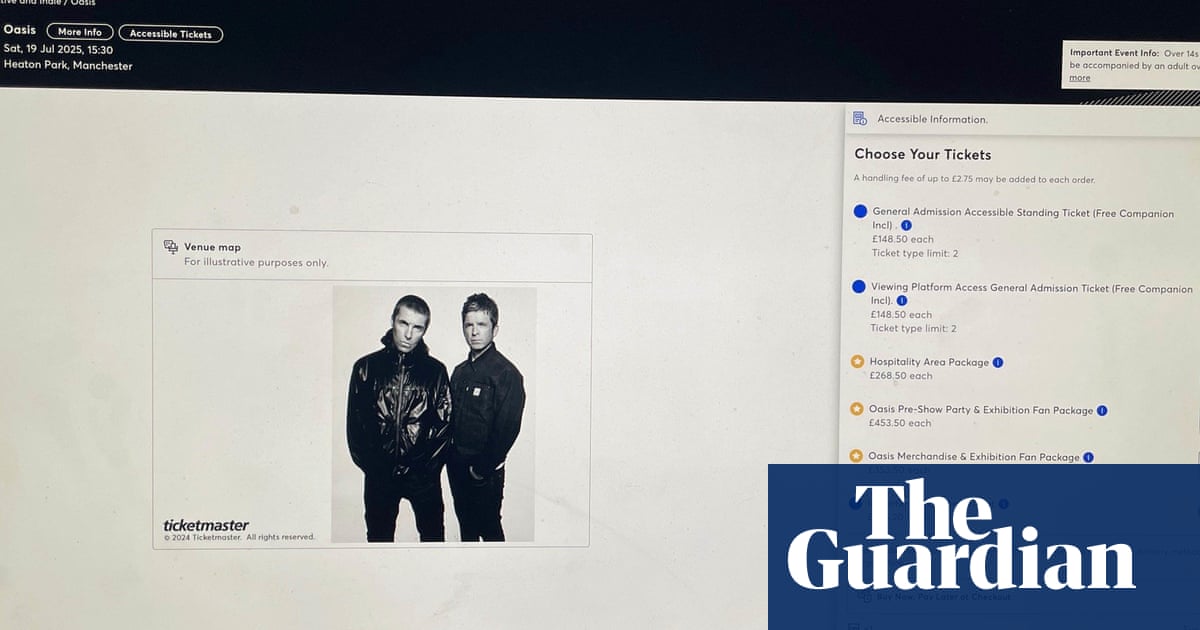

By 2.30pm on Saturday, all of the £135 standing tickets for the Manchester concert on 20 July next year had gone. The only ones left were “in demand standing” which – given the £337.50 price tag – I naively assumed would at least get you a better view.

Ten seconds. Nine seconds. Eight. There was no time to deliberate or ask friends whether they could afford such a hefty outlay. Do I choose principle or pleasure?

The overdraft alert from my bank this morning reminded me that I had chosen the latter: £1,423.55 for four “in demand standing” tickets – of which £73.55 is service charges and processing fees.

The total, including insurance, comes to a stomach-churning £361.13 a ticket. That’s the same price as Glastonbury festival and more expensive than four nights in Sharm El Sheikh. Was it worth the aggravation?

Any elation was pretty quickly subdued by the enormous financial cost. We had spoken beforehand about how much we could stomach paying to see the band we grew up adoring (even though, let’s be honest, the last couple of times we saw them – in 2008 and 2009 – they were underwhelming).

We agreed that £250 for hospitality tickets was just about OK. These were the most expensive tickets when prices were revealed last week; the first fans knew of the “in demand standing” ticket was when they reached the checkout.

The fact Oasis are playing so close by – I live under a mile from Heaton Park – made the emotional pull greater. I couldn’t miss it.

Ticketmaster rely on this emotional response to get people to pay such extortionate sums. And after queueing for six hours – and being kicked out several times for bot-like behaviour, despite simply having one tab open – the impulse to buy is overpowering.

after newsletter promotion

About 10,000 people an hour were dropping out of my queue by about midday on Saturday after either purchasing, being priced out, or, equally likely, giving up. At 1.12pm, 34,000 were ahead of me. Just over an hour later, it was my turn to buy.

Stan Collymore, the former footballer, compared this “buzz of getting into the buy phase” to the same dopamine hit that gamblers experience. He added: “At that stage, £150 to £400 price rise no longer is a choice, it’s an impulse buy. An unethical/should be illegal business practice.”

With any rush comes a crash. The feeling many fans will have today is of being exploited – not just by Ticketmaster but, worse, by the artist and their management who agree in advance to introduce this system of “dynamic pricing”.

Having opted for pleasure over principle, there is the feeling too that we are complicit in what feels like a supersonic swindle.