Formula 1’s divisive 2026 regulations will be changed to address the biggest fears teams have raised so far, but only after an initial version is approved in the “most restrictive” form.

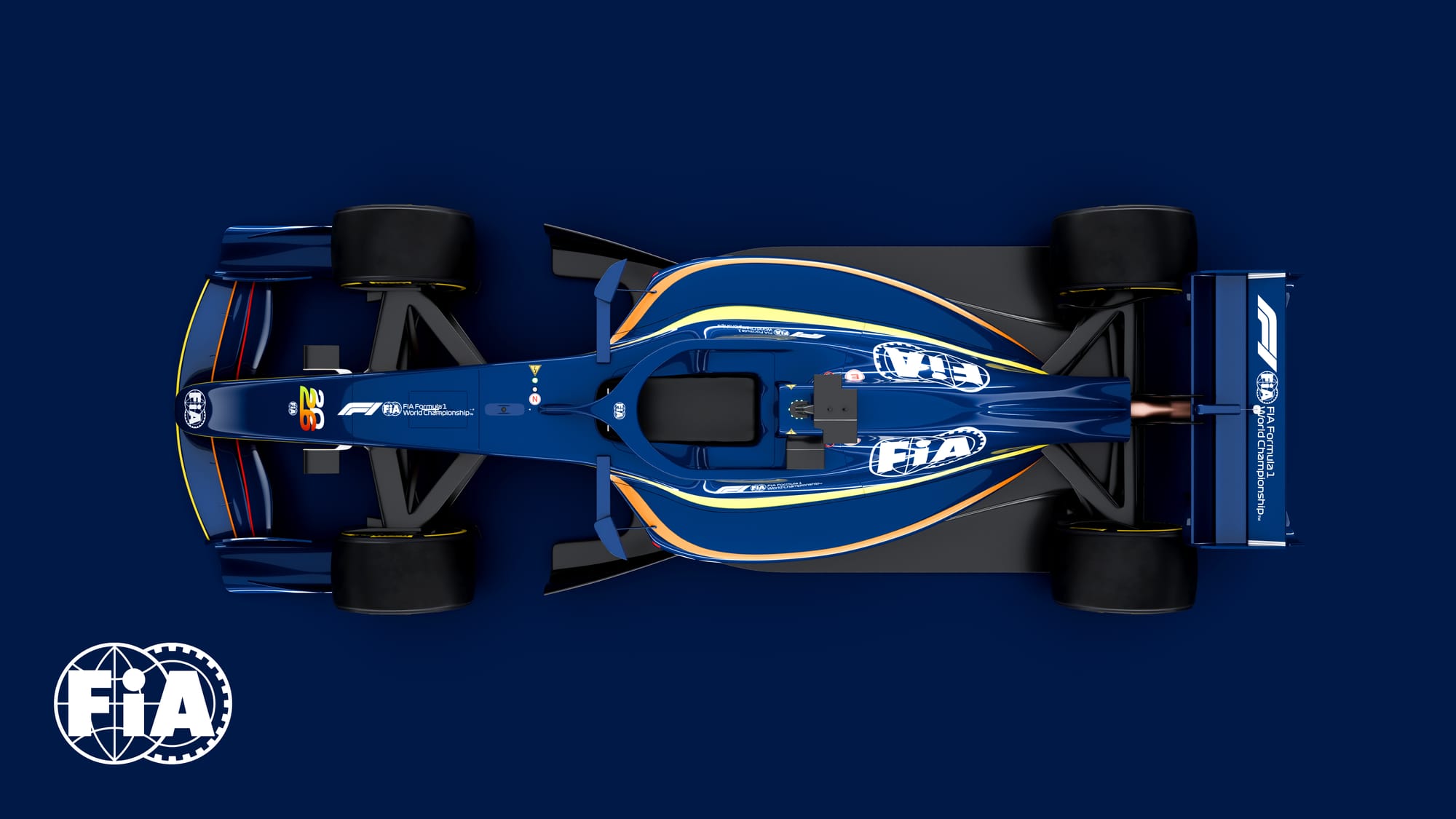

Concept images and a first tranche of detailed information were shared by the FIA this week, based on draft regulations that will be presented to the World Motor Sport Council on Tuesday next week, in what FIA single-seater director Nikolas Tombazis calls a “very extensive manner”.

The aim is to have them approved towards the end of the month, and a primary driver of releasing what the FIA has now is to make sure the “full picture” was shared early rather than through leaks.

But like all FIA regulations, these were never likely to be the final form with F1’s governance setting out a clear process for changes to be agreed and implemented before 2026 comes around.

“Most important of all is the World Council discussion, and hopefully the approval is the first step,” said Tombazis. “We’re not in the final set of regulations yet.

“We do have quite a few things that we need to define and discuss with the teams. We are fully conscious of some of the concerns and these are things that we class as the refinements that still need to take place.

“Between, let’s say, the end of the month, when these regulations will hopefully be published, and the start of 2025, when teams can start aerodynamic development, we do expect a reasonable amount of extra work to be done in full consultation with the teams, with FOM and everybody else.

“And hopefully that will then lead to some refinements that will be submitted to the World Council maybe a bit later in the year and hopefully approved.”

MORE FREEDOM WILL BE GRANTED

As Tombazis referenced, the current plan for 2026 is so controversial in some areas that some concerns have been raised about how mature the rules will be when they are initially approved.

Teams have called for extensive changes to be made over the next weeks and months to ensure the objectives of the rules can actually be met.

The FIA is already aware of the issues teams have with the draft regulations based on discussions in the Technical Advisory Committee, the group that helps shape regulatory decisions.

FIA single-seater technical director Jan Monchaux said the plan was to green-light a restrictive initial set to meet the deadline for approval demanded by the International Sporting Code – and then open up the regulations as necessary thereafter, through discussion with the teams and other stakeholders.

“They have expressed concerns for sure,” Monchaux said.

“Typically teams are always reluctant to large changes, so [there is a] bit of an ongoing compromise that needs to be constantly found.

“Effectively, the approach we have is we needed to respect framework in terms of date of publication. The regulations as presented and hopefully voted in will be the most restrictive teams will see.

“We think it will be far easier in the next months to start increasing the freedom and change aspects of the regulations that seem too constrained, than the other way round.

“Because they’ll all agree on more freedom. The other way round would be a lot of freedom in their ability to design the cars, then we realise in October or November we don’t necessarily want it because it might risk some of the targets.

“It’s more reasonable, this approach, since we have a solid basis to start discussions, and to review some areas where we offer little or no freedom.”

‘DETERMINED’ TO REDUCE WEIGHT

Question marks have been raised by teams about the viability of the 30kg weight reduction, with the minimum mass dropping from the current 798kg to a planned 768kg in 2026.

The FIA is confident the target is “challenging but feasible”, although work is still ongoing with teams in terms of understanding what weight savings can be achieved.

“We are quite determined to reduce the weight of the cars,” said Tombazis. “We’ve been working on a range of assumptions based on work that Jan has been doing in collaboration with the teams.

“We’ve got a range of areas where we know weight will go up and we’ve got a range of areas where we know weight will go down. What we have as a target is based on a challenging but what we feel is feasible target.

“Clearly, we’re going to be still asking teams for some estimates about the weight savings they can make and so on and we’re going through that process.

“But we are pretty determined to reduce the weight in a significant way, which is the first time this is happening I think in F1 since probably the 1980s or something.”

Tombazis also said that suggestions the driver minimum weight regulation is being dropped are inaccurate.

The regulation was introduced in 2019 effectively to set the minimum weight of the drivers at 80kg through the addition of ballast to the seat if required, but this figure will now rise by 2kg.

“No, it’s not correct,” said Tombazis when asked if the driver minimum weight regulation is being dropped. “The discussion has been whether the allowable weight should be 80kg or 82kg.

“The feeling was that 80kg could penalise a few slightly heavier drivers and we’re going to be going to 82kg.”

A ‘LOW BAR’ FOR PERFORMANCE

Massive changes to the performance profile of the cars are inevitable with the intention of cutting downforce by 30%, reducing drag by 55%, having slightly narrower tyres and overhauling the characteristics of the engine by reducing the V6 output and almost tripling the power from the MGU-K.

It’s led to worries about how fast the cars will be on the straights, and how much slower they will be through the corners, adding up to an overall performance deficit compared to now that detracts from F1’s status as the pinnacle of motorsport.

Monchaux admitted that top speeds will be “slightly higher than now” but insisted that will be closely monitored, and performance parameters controlled as required, to avoid speeds running out of control. The intention is for straightline speeds to be comparable to now, “plus or minus” a couple miles per hour.

“We’ll make sure that the top speeds are not reaching levels which would be a safety concern and we have means to do that,” Monchaux said.

“We can impact on the low-drag configuration, forbidding it on given straights or reducing how much you can open [the wings], to control top speeds.

“Similarly, deployment of electrical energy, we have the provision if needed to readjust where we feel is necessary to achieve top speeds in reality similar to now.

“We’re not interested in absurd risks. If we took no action the risk would be there but we’re aware of it.”

The FIA is somewhat unapologetic about plans to slow the cars down in corners, though. The desire now is to slow them down but make them more “nimble” – so they aren’t as quick, but they change direction better, aren’t as lazy to drive, and by extension can be raced better.

But Monchaux said the FIA is happy to discuss what an “adequate” downforce level would be once teams mature their designs and simulation work with an initial set of confirmed regulations. That means evolving the regulations, most likely in the floor, to add more downforce to the cars than what is currently expected.

The performance profile has also triggered a concern that the laptimes will be much slower than now, and potentially only a few seconds faster than Formula 2 pace. Tombazis called those fears “accurate” based on a snapshot of the draft regulations, but that as things evolve, this will be “100% resolved”.

“We have full expectation to make steps in performance,” he said. “That’s exactly why we’ve set the bar reasonably low to start with so we can build up with collaboration of the teams.

“To increase downforce of these cars is easy if you have regulatory freedom. That’s the steps we’re going to take.”

The changes to the tyres, which will be 2.5cm narrower on the front and 3cm narrower on the rears, will result in a small drop in grip. A first test will take place in September to maximise the development time for the tyres.

ACTIVE AERO ‘SIMILAR TO DRS’

One of the major changes in the 2026 regulations is the introduction of active aerodynamics. As announced earlier in the week, drivers will be able to switch between X-mode [low drag for straightline speed] and Z-mode [higher downforce for corner speed] with both the front and rear wing being active.

When asked by The Race to elaborate on how this system will be controlled and the regulations that will govern it, Monchaux said that much of the detail is yet to be finalised based on discussions with the teams.

However, he likened it to the current DRS regulations, as well as confirming that there will be parameters in place to prevent it being activated while there is much or even any lateral load on the car to ensure it is only used on straights.

“All that is currently still in discussion with the teams,” said Monchaux. “So it’s not like we have fully described all the detail of how and when you activate.

“The general line we will follow is similar to the DRS. So the DRS, you need to tick the box in terms of distance or laptime distance to the car in front of you at a given point, and then the driver can deploy. But it’s a driver that pushes a button and deploys the DRS. And he is also closing it.

“If you think about how the DRS works, we think the approach for the X-mode would be exactly the same. Some conditions are being fulfilled, like very low or no lateral acceleration, so effectively exiting the corner. If these conditions are ticked off, then the driver will press a button, and it’s not going to be automated, then his DRS and the front wing will open up to go in the low-drag [mode]. Then shortly before arriving on the braking zone, he will deactivate it.

“And if not, we will make sure it does deactivate. The approach on failure analysis, or FMEA [failure mode and effects analysis], the system could be subject to, it will be subject to the same approach that back in the day was done with the DRS. And we’ll just have the same extremely rigorous approach, making sure that the system, once deployed the first time during the winter test, will be just doing what it’s supposed to do and not subject to constant reliability issues or even worse, safety.

“That a few teams might have a few hiccups in the first winter test is to be expected, but I genuinely think the experience gained over the years on the DRS should be perfectly transferable on the front and therefore the system will not be a huge challenge for the teams in terms of can we get it to work and can we get it to work safely, reliably, because it’s going to be almost on every straight line. This we are not too worried about.”

POWER UNIT REGULATIONS COULD BE TWEAKED

The 2026 rules have been led by the power unit regulations, which were published in August 2022. But while these won’t change dramatically, the FIA believes the engine manufacturers are open to making tweaks if they are necessary to achieve the objective of the wider rules package.

This was something McLaren team principal Andrea Stella suggested is needed, arguing that “it’s time that all parties understand that they need to contribute to the success of this”.

Tombazis said that although the power unit regulations are ratified and published – and now onto their sixth version – meaning there are restrictions in terms of how changes must be voted through, the manufacturers will be open to potential changes in the way the rules allow the power to be managed.

“There’s a slightly different position in terms of governance in the power unit, as we’re already under governance agreement in relation to the power unit regs, which means that any tweaks that may be necessary will still need to be agreed with the power unit manufacturers and cannot be done unilaterally,” said Tombazis when asked by The Race about the scope for the engine rules to be modified if required.

“But because there’s generally speaking a very good spirit of collaboration. If there are some tweaks needed I’m quite confident the PU manufacturers would help and be collaborative.”

The objective for the power units is to produce roughly a 50/50 split in terms of V6 power and electrical power, but there are concerns that the way the power is created and managed could make it difficult to hit performance targets.

While the fundamentals of the regulations won’t be changed in terms of the architecture given manufacturers are already well-advanced in developing them, there is potentially scope for small changes in the rules governing the production and management of power.