Cotton conquered the world. Not bad for a notoriously fussy plant that requires vast quantities of water, lots of sun and moderate heat, and which is easily decimated by drought, flooding or pests. In 1913, it accounted for 80 per cent of the fibres consumed globally; wool was a distant 16 per cent. It was dethroned in the mid-20th century by the development of synthetics, but still accounts for a quarter of total consumption today.

Historically, it powered global trade and industry. The historian Eric Hobsbawm said, in 1968: ‘Whoever says Industrial Revolution, says cotton.’ And calico, a relatively simple cotton textile, helped pave the way for all of this.

Calicoes are plain-weave cotton fabrics decorated with simple designs in one or more colours. They are generally woven in a ‘grey state’ (meaning undyed), before being bleached and printed.

Unlike chintz, a close relative, calico is unglazed and so has little or no sheen. It originates from India, and the earliest known mention of it is from the 12th century, when Hemachandra, a scholar and poet, described a chhimpa, or calico print, decorated with a lotus design. The oldest surviving fragment dates back to the 15th century and, although Indian in origin, was actually found in Cairo, suggesting that even then this was a fabric coveted abroad.

By the mid-17th century, Europeans had also gained a taste for Indian calicoes, which were lighter, brighter and more comfortable to wear than homegrown woollens and linens. The Dutch and British East India Companies seized the opportunity. By 1727, a writer in London groused that, ‘On a sudden, we saw all our women, rich and poor, cloath’d in Calico, printed and painted; the gayer and more tawdry the better’. The fabric also ‘crept into our houses, our closets, and bedchambers; curtains, cushions, chairs, and at last beds themselves were nothing but Calicoes or Indian stuffs’.

Its popularity was such that Britain’s textile industry began to suffer, resulting first in the passing of protectionist laws – the CalicoActs – and later in the development of machines that could imitate the skill of Indian weavers and dyers. This scramble to reproduce popular calicoes cheaply and locally fuelled the Industrial Revolution.

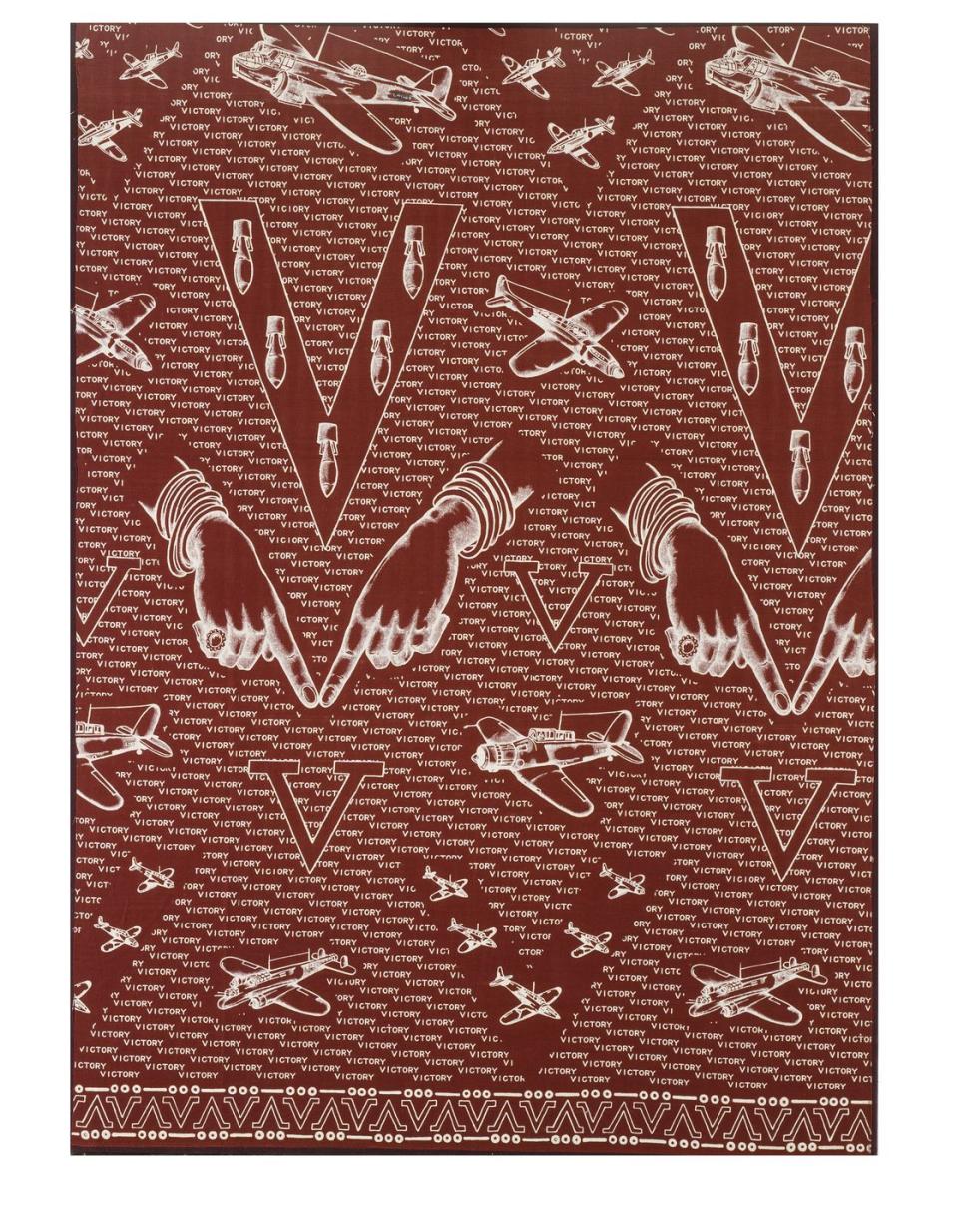

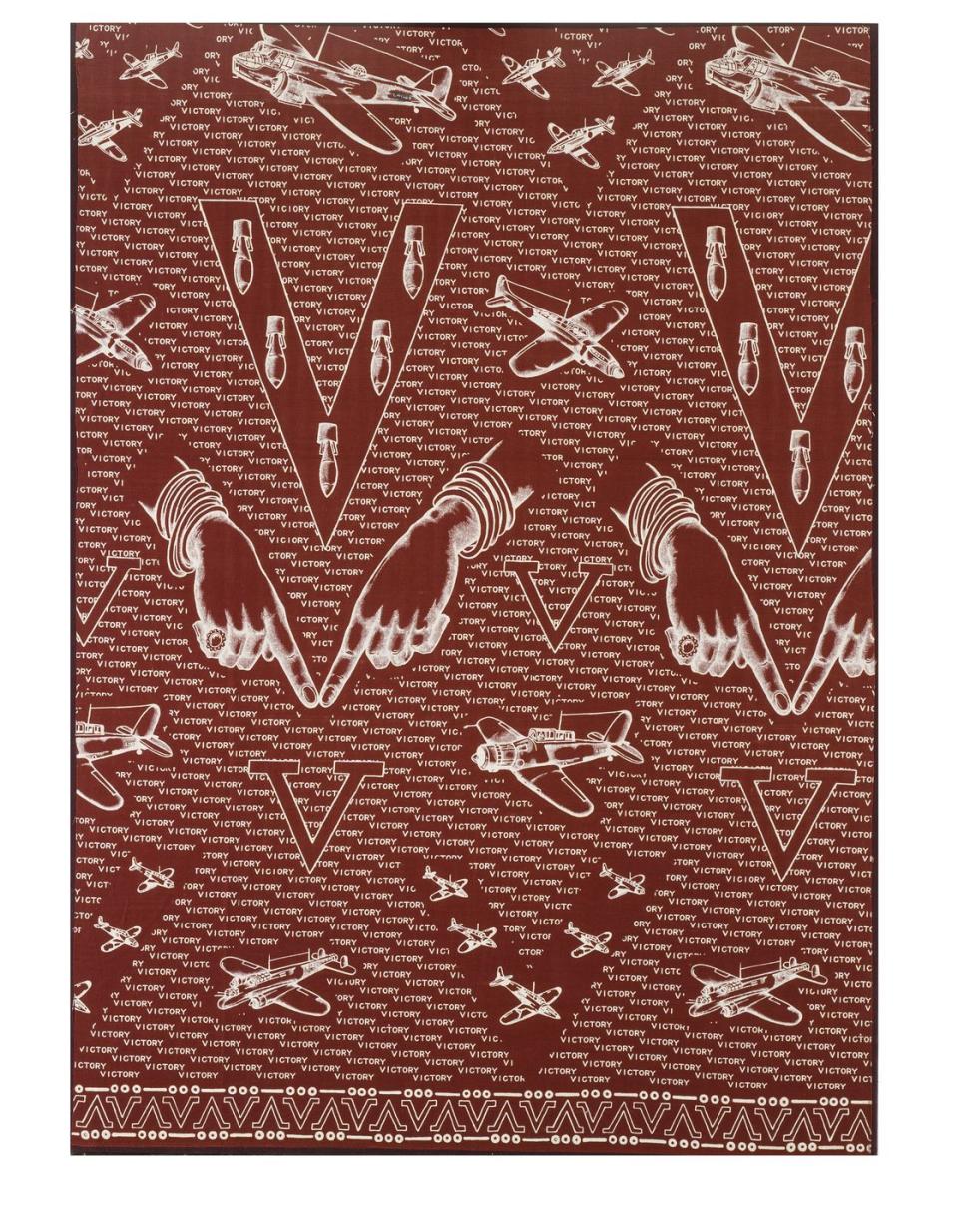

Calicoes are a peerless canvas for creativity and changing tastes. The Calico Printers’ Association, formed in Manchester in 1899, accounted for 85 per cent of Britain’s printed cloth and continued creating innovative and fashionable prints into the 20th century. A rust-red example, produced in 1941 and now held at the V&A, features planes, bombs and ‘V for Victory’ motifs. Even the decorative border is made up of a series of dots and dashes – Morse code for ‘V’.

Today’s calicoes similarly mirror today’s preoccupations, whether that’s for maximalist mixtures of pattern, bold shots of chartreuse or a cosy retreat from intrusive technology. Calico can do it all.