When Kurt Cobain imagined his visceral grunge rock stripped to its bones, he pictured a shrine. “He said, ‘I want candles and Stargazer lilies,’” remembered Alex Coletti, producer of Nirvana’s celebrated MTV Unplugged show. “I said, ‘Like a funeral?’ He said, ‘Yes, exactly.’”

Sure enough, when the album recording of Nirvana’s flower-strewn MTV Unplugged in New York was released in November 1994, 30 years ago this week, Cobain seemed to be singing his own elegy. Seven months after a shotgun suicide that stunned the world, here he was, alive yet powerfully wounded, reaching into the gristle of songs such as “Polly”, “Something in the Way” and “All Apologies” in their most cathartic form – pulling out something raw, bruised and inconsolably honest. The album would reach No 1 on charts around the world, including the UK and US, and sell over 14 million copies, a vivid last testament to Cobain’s Nirvana, and a glint of a folk-rock revolution that would never come to pass.

Indeed, MTV Unplugged in New York itself almost never happened. From the off, this righteously punk-hearted band – shot so suddenly and unexpectedly into the heart of the mainstream with 1991’s Nevermind – were wary of the artistic compromise involved with collaborating so closely with the corporate MTV devil. The Unplugged series hadn’t exactly exuded punk credentials to that point, with the likes of Elton John, Sting, Crowded House and Aerosmith taking up the hollow-bodied baton. Eric Clapton had turned his 1992 appearance into the bestselling live album of all time, thanks to a heartbreaking rendition of “Tears in Heaven”.

“We’d seen the other Unpluggeds and didn’t like many of them,” Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl told Rolling Stone in 2005. “Most bands would treat them like rock shows – play their hits like it was Madison Square Garden, except with acoustic guitars.” But acts such as REM, Neil Young, The Cure and fellow Seattle grunge beasts Pearl Jam had risen to the challenge enough that Nirvana felt they could stamp their own subversive artistry onto the format – notably by defying MTV pressure to play their biggest hits in favour of more sombre tracks and choice cult covers.

“Kurt wanted to prove to himself that he could do this in an artistically successful way,” Geffen A&R man Mark Kates told The Ringer in 2018. “His creative mind at that time was going more in a quieter direction.”

All the better, perhaps, to silence the screaming. As the recording date approached, Cobain was in the vice-like grip of his heroin addiction. Rehearsals for the show, held in the SST rehearsal facility above a New Jersey pinball machine store accompanied by cellist Lori Goldston and new guitarist Pat Smear, were shaky at best, downright sloppy at worst. Though Nirvana had been playing an acoustic segment with Goldston on their recent In Utero tour, an entire show of stripped-down songs was tough to hang together. “By the end of the second day I was left thinking at this point it could be a mistake to proceed with the show,” their guitar tech Earnie Bailey told The Ringer. “The rehearsals were so loose; I don’t remember them making it through a full set.”

Anxious about the show, jittery from heroin withdrawal and frustrated at MTV’s icy response to their intended guest musicians – Cris and Curt Kirkwood from psychedelic country-punk band the Meat Puppets – the day before they were scheduled to record, Cobain refused to do the show. MTV’s Amy Finnerty put it down to run-of-the-mill cold feet. “People are like, ‘Oh my God, he’s gonna cancel, he’s gonna quit,’” she recalled. “No, he was just having a feeling.”

Nonetheless, it was a tense morning at Sony Studios on 18 November 1993. MTV’s gentle prods towards playing major hits like “Smells Like Teen Spirit” had been firmly rebuffed and Colletti was concerned that Cobain’s guitar – a Martin D-18E, complete with a Fender amp that was disguised as a monitor onstage – was so fundamentally electric it might slaughter the show’s entire conceit. Meanwhile, at the behest of a nervous fire marshal, production designer Tom McPhillips spent the morning dousing the set in sand in case any of the candles fell over. Coletti had also bought Grohl some brushes and lighter drumsticks to dampen his natural power for the performance. But it would all be for naught if the band didn’t show.

When Nirvana did finally arrive that afternoon, with a drug-shaky Cobain sipping on a large mug of tea and insisting – despite the studio’s tight security – on heading outside to greet the audience of specially selected fan-club members queueing along 54th Street, the relief was tempered with a frisson of uncertainty. The rehearsal run-through was halting and erratic; Cobain’s mood was unpredictable. “There was no joking, no smiles, no fun coming from him,” one observer said later, “everyone was more than a little worried about his performance.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

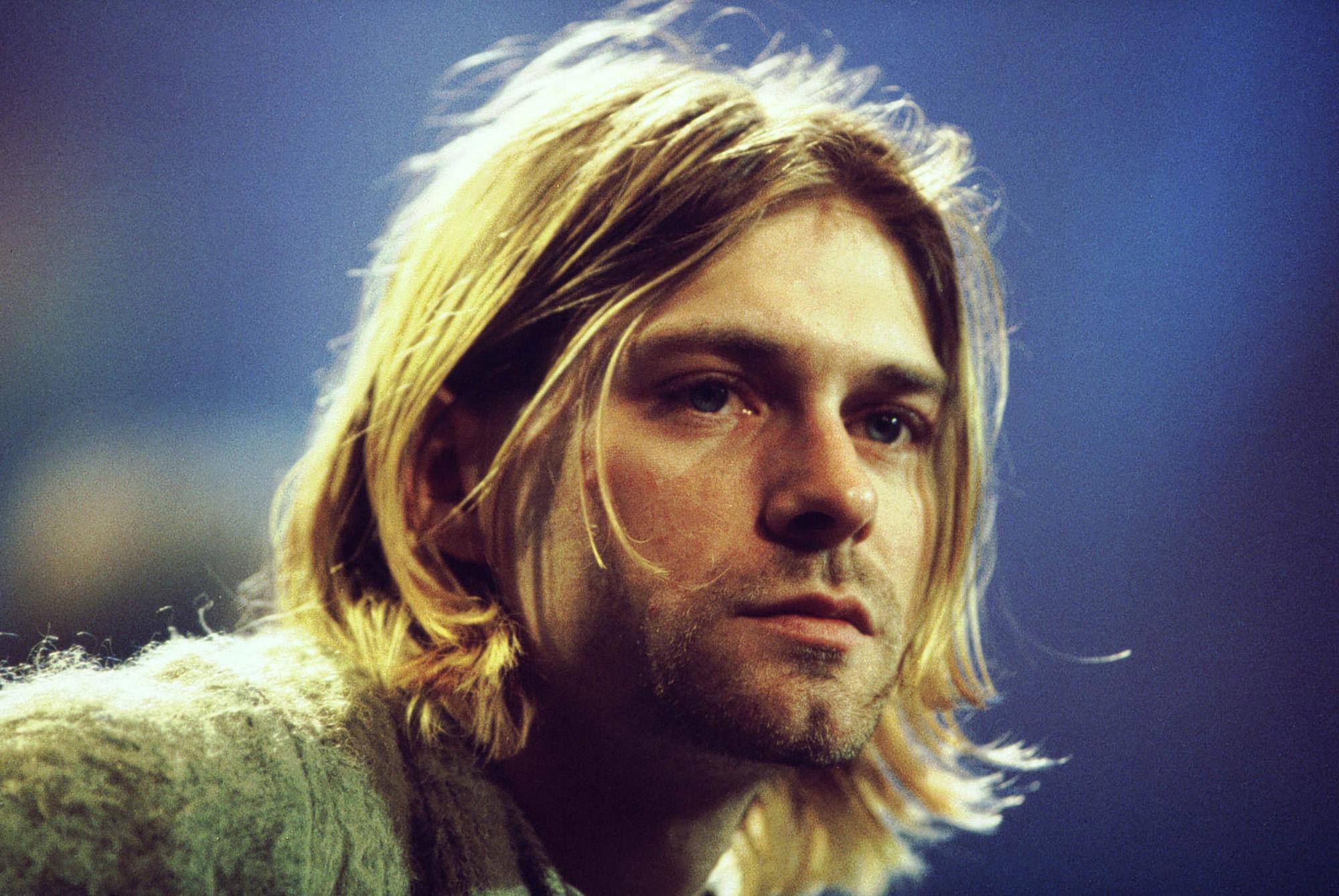

As he took to an office chair behind a balcony of lilies, clad in a T-shirt of San Francisco fem-punk act Frightwig and a ragged grey cardigan that would eventually fetch $334,000 at auction, Cobain began the set with trepidation. “This is from our first record. Most people don’t own it,” he muttered ahead of the opening chords of “About a Girl” from 1989’s Bleach. “We went into it so nervous and shaky,” bassist Krist Novoselic told Bass Player Magazine in 2018. But the nerves swiftly evaporated. “After the first song, and the reception they got, they settled in,” said the Unplugged album producer, Scott Litt.

Though Cobain ended that first number with a forced rictus grin – a sly sop to his management who’d told him to smile more onstage – the intimate style and setting of Unplugged in New York allowed fans into the fragile core of his songs, previously hidden behind a protective wall of abrasion. It afforded a glimpse into Cobain’s damaged mindset, too. “You kind of had Kurt Cobain at his wits’ end with everything going on with him in his life,” said Nirvana biographer Charles R Cross. “He was truly falling apart. Physically, mentally. He hadn’t been sleeping. And yet, on stage, once the tape starts running, it’s absolutely mesmerising.”

As they reached their first cover, a gentle rendition of Scottish indie rockers The Vaselines’ “Jesus Wants Me for a Sunbeam” (renamed “Jesus Doesn’t Want Me for a Sunbeam”) with Novoselic grooving folksily away on accordion, Nirvana’s ethos of twisting the mainstream to their countercultural will began to reveal itself. Cross points to the setlist – six covers, four songs from Nevermind, three from In Utero, and one from Bleach – as the least profit-driven Unplugged show in the series’ history. And although Cobain warned the crowd “I guarantee you, I will screw this song up” before taking on David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World”, the band’s confidence bloomed.

Novoselic put this now legendary performance down to a determination not to be beaten by the song. “I sat on the edge of my bed the night before the show and tried to figure out what the hell the bass was doing,” he told Bass Player. “I knew if I could get the bass run down, it would bring it all together. I sat for a half hour and played it over and over again, and I got it locked in… I still can’t believe we pulled that show off.”

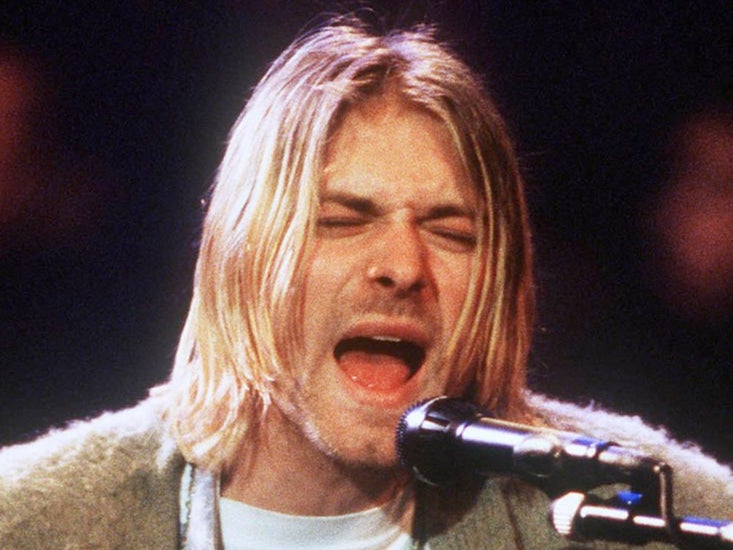

“I didn’t screw it up,” Cobain said on the night, mood noticeably lifting. A laidback tone took hold as the band discussed who should start “Pennyroyal Tea” and in which key. Grohl and Smear retreated to the back of the stage for beer and cigarettes as Cobain performed the song solo, pulling it down to a quiet mumble midway through. “That moment when he breaks,” Cross told The Ringer, “you think, ‘This is over. Everything is over. Not just the Unplugged show. Kurt Cobain himself is over. The entire career of Nirvana is over.’ And then he kind of pulls it together and moves forward. To me, it is his most vulnerable moment and one of the reasons that I think it’s his greatest single moment on stage.”

At the song’s close, Novoselic wandered over to reassure Cobain that the cover “sounded good”. “Shut up!” Cobain wryly snapped, and the pair set about bickering brotherly over what to play next. Cobain didn’t want to play “Dumb” and “Polly” back to back “because they’re exactly the same song” – his oft-hidden humour peeking through. Later, waiting for the Meat Puppets to set up behind him, he sat reading a fanzine and wisecracked: “What are they tuning, a harp?” When a crowd member yelled out a request for Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird”, Cobain instead led the band in a brief, drunk-drawled rendition of the same band’s “Sweet Home Alabama”.

It killed me, particularly where he paused before the end and gasped

Scott Litt, album producer of ‘Unplugged’

It was the closing song, though, that those close to Cobain felt was most revealing. Ignoring catcalls from the crowd for “Sliver”, “In Bloom” and “…Teen Spirit”, and Grohl’s comic suggestion of Pearl Jam’s “Jeremy”, Cobain struck up “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” by Lead Belly. “F*** you all, this is the last song of the evening,” he declared, letting on that someone had tried to sell him the revered 1930s blues and gospel singer’s original guitar for $500,000. Now considered a masterwork of mood-building and release, the song climaxed with Cobain’s scorched howl – “I’d shiver the whole night through” – sounding as much a personal exorcism as a full-hearted tribute.

For those in the room, it felt as though Cobain – an icon of angst who had almost named Nirvana’s third album, In Utero, “I Hate Myself and Want to Die” – was pouring his well-publicised pain into the song. “It f***ing killed me, particularly where he paused before the end and gasped,” said Litt, and Finnerty felt it too: “He made time stop.” Spin editor Craig Marks knew instantly he’d seen rock history being written. “You knew the dead second that it was happening that you were witnessing something phenomenal,” he told The Ringer. “You didn’t really even know he had it in him.”

Backstage, Coletti was tasked with coaxing the band back out for more songs. Cobain thought about it for a second, then said: “I don’t think we can top the last song.” Coletti immediately wrapped the shoot. Back at the band’s hotel, though, Cobain worried to Finnerty that no one had liked the show. “He’s like, ‘I’m really bummed… It was really bad’,” she said. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, you’re out of your mind… people just saw their version of God playing three feet in front of them.’”

In the wake of Cobain’s death, the show’s funereal tone took on a new meaning. The band’s light-hearted between-song banter was also edited out of the original TV broadcast. Look back at the full footage, though, and the performance actually represents the most honest, bare, and rounded look at Kurt Cobain available to us in concert form: his dry wit; his flitting between anxiety and confidence; his uncompromising punk principles; his pained power and his sublime songcraft.

Cross argued that, for the generations of fans who discovered Nirvana after the fact, it was the perfect entry point to understanding Cobain as a songwriter, singer, and person. “You’re getting unfiltered Kurt there,” he said. “There’s no lens you’re seeing him through. You are seeing him.” For that hour at least, unplugged and undisguised, Cobain came exactly as he was.