Getty Images

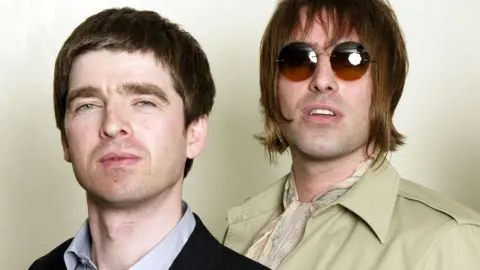

Getty ImagesThe first sign that the sibling warfare between Noel and Liam Gallagher was beginning to calm came during an interview last month.

Reflecting on the band’s sound, Noel told journalist John Robb: “It’s difficult to explain – when I would sing a song it would sound good, when [Liam] would sing it, it would sound great.”

Hearing Noel compliment his brother publicly after 16 years of insults certainly turned a few heads. But few people expected that just days later, the band – who broke up on the same week in 2009 – would dramatically reform.

A blizzard of headlines and a social media frenzy followed, cutting through the national psyche like the band’s two era-defining nights at Knebworth in 1996.

And now, we have a reunion. Tickets for the Oasis comeback tour went on sale on Friday for the pre-sale, and Saturday for the general sale, with fans racing to beat each other the booking queue.

But why reunite now?

There are several reasons – but the financial incentive is surely on the list.

£50m each?

“A deal would’ve been struck early by promoters, and I’ve heard numbers bandied around of the Gallagher brothers earning £50m each,” says Jonathan Dean of the Sunday Times, who first reported the reunion tour. That £50m estimate was made by Birmingham City University about the initial 14 dates.

“I think that is probably true, ticket prices are higher than they used to be.”

But, he notes, figures are difficult to estimate until the full extent of the live shows is known.

“This is being called a world tour, but currently it’s not going further than England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland,” he notes. “It doesn’t go to the rest of Europe, to America, so I think any earnings are completely up in the air until we know how far this tour is going to spread.”

EPA

EPABirmingham City University estimated that the initial dates could, potentially, bring in roughly £400m in ticket sales and other add-ons.

For comparison, Take That’s Progress Live tour in 2011 brought in an estimated $185m (£140m).

The Spice Girls – minus Victoria Beckham – caused Ticketmaster to crash for their 13-date tour in 2019, which earned an estimated $78m (£60m).

Abba were able to launch a hugely successful comeback without even performing live themselves, with the digital avatars used in Abba: Voyage said to be making $2m (£1.5m) in London per week.

But bands – including Oasis – are also presumably attracted to the idea of building their legacy as well as their bank balances.

When Blur played two nights at Wembley last year, critics’ reviews were breathless in their praise.

Banking on a sibling rivalry

To some, the Gallaghers’ sudden claims of a truce after years of ferocious barbs might cynically echo the Sex Pistols’ 1996 reunion. Frontman John Lydon admitted at the time that although the band still hated each other they had “found a common cause, and that’s your money”.

But although “money is king here”, says Robin Murray, music editor of Clash magazine, the timing is also arguably “quite natural”.

He notes both Gallagher brothers have just completed their most recent solo musical commitments. “There’s definitely an element of truth to this simply being two people, with a particular bond, being in the right place at the right time.”

Dean notes the Gallaghers are “very rich men anyway”, so there will have been other motivations.

“I think the family thing is key, I just think they’re older, and their ages has made them come together,” he says.

And their long rivalry, with its familial ties and shared legacy, has equally helped bring the band back together, suggests music psychotherapist Katerina Georgiou.

Both Gallaghers have had solo career success. But it’s Liam’s star that has risen the most in recent years. “The brothers spark off each other marvellously and there’s always been that edge of competition,” says Dr Georgiou.

“Of course seeing Liam sell out Knebworth and carry a Definitely Maybe tour on his own will have risen the stakes for Noel and vice versa, as Noel’s movement away from Liam pushed Liam to prove himself to his brother.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe pair will no doubt benefit from changes to the wider industry landscape. Streaming wasn’t around during Oasis’s heyday, but it has helped them reach new audiences in the intervening years.

Carl Smith, editor at the Official Charts Company, says “the timelessness of Oasis’s material transcends generations and holds up so well in the streaming era”.

It’s echoed by Dean, from the Sunday Times, who says their music is accessible. “What Oasis do is simple, and I don’t mean that in a bad way, it’s songs of escapism and going off and doing your own thing and being free of the drudgery of daily life and work, but done in a simple, slightly raucous, singalong way.”

Before the reunion had even been announced, Spotify said Oasis streams increased by more than 160% globally just on the strength of the rumours.

Another surge following the announcement led to three of the band’s albums going back into the top five on Friday’s official chart, with their greatest hits album increasing by 332%.

Many new Oasis fans are young women – capturing younger fans is crucial for future-proofing the band financially.

Liam’s popularity, in particular, is helping to carry the band’s music for a new generation. Just last week, aged 51, he headlined Reading Festival, a favourite of GCSE and A-Level students.

With reunions, come risks

For all the heady temptations reunions bring artists, they can easily go wrong.

Jennifer Lopez this summer cancelled her greatest hits tour midway through its run over poor ticket sales. Music journalist Michael Cragg, author of 90s and noughties pop book Reach for the Stars, says she had already “flooded the market” with several Netflix projects, making her music feel like “almost like the last thought”.

And the unexpected return of Oasis’s iconic Mancunian contemporaries The Stone Roses in 2011, after a 20-year absence, highlighted the danger of overpromising and underdelivering. Their initial comeback dates were rapturously received, but new singles fell flat and a new album never materialised.

Oasis’s return has, so far, avoided this pitfall, says the Independent’s music editor Roisin O’Connor.

For now, the band haven’t promised the world – they’re gauging reaction to the tour first, a tour which itself was a surprise.

“There’s no indication that they plan on releasing any new music, meaning there isn’t that risk of fans feeling let down if the material didn’t match those earlier albums,” O’Connor says.

But this doesn’t mean the tour isn’t without risk.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere’s a potential threat to Oasis’s working-class credentials, for example. If this tour becomes financially and logistically inaccessible, it could undermine this image.

Standing tickets for the Oasis tour are priced around £150, but premium packages cost up to £506. Some unofficial re-sale tickets are going for £6,000, though the band has warned these could be cancelled.

During Saturday’s sale, “dynamic pricing” on Ticketmaster, where prices rise in line with demand, set some remaining tickets to around £355 plus fees – up from £135 when the sale began.

Tickets to see the band at Knebworth in 1996 cost about £22 – but that doesn’t account for inflation and the new era of tiered pricing.

The pricing concern and clamour for tickets has also led to discussions around gatekeeping.

Some older fans feel they shouldn’t be in competition for tickets with fans who weren’t even alive the first time around. But many counter that music does not belong to anyone, it’s there for all to enjoy.

Last chance to see them?

The cultural impact of the 2025 shows is likely to be huge, suggesting Oasis “have already stamped their foot over next summer”, Dean says.

The fact the band have ruled out playing Glastonbury next year is likely to boost demand of their own tour: fans have been told the only way to see them live is to buy a ticket.

The appeal of the Oasis live shows is further underlined by the prospect of it being the last chance for fans to see them.

“I think this will be viewed as the latest – possibly final – chapter in the Oasis story,” says the Independent’s O’Connor.

“A moment of catharsis for fans who wanted that closure or a chance to see the band for a final time, and hopefully a mending of fences for Noel and Liam after all these years.

“After that, who knows.”

Additional reporting by Steven McIntosh