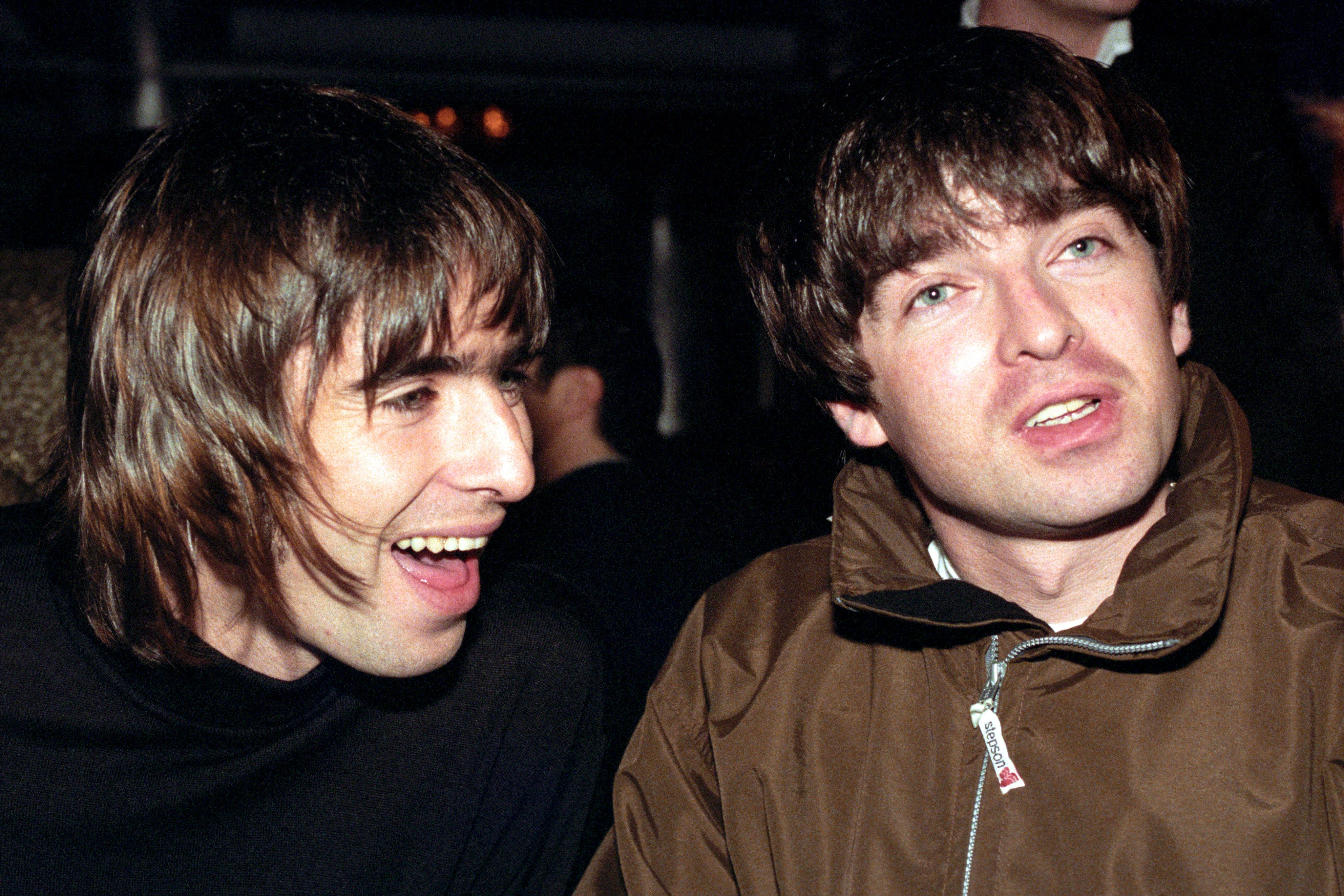

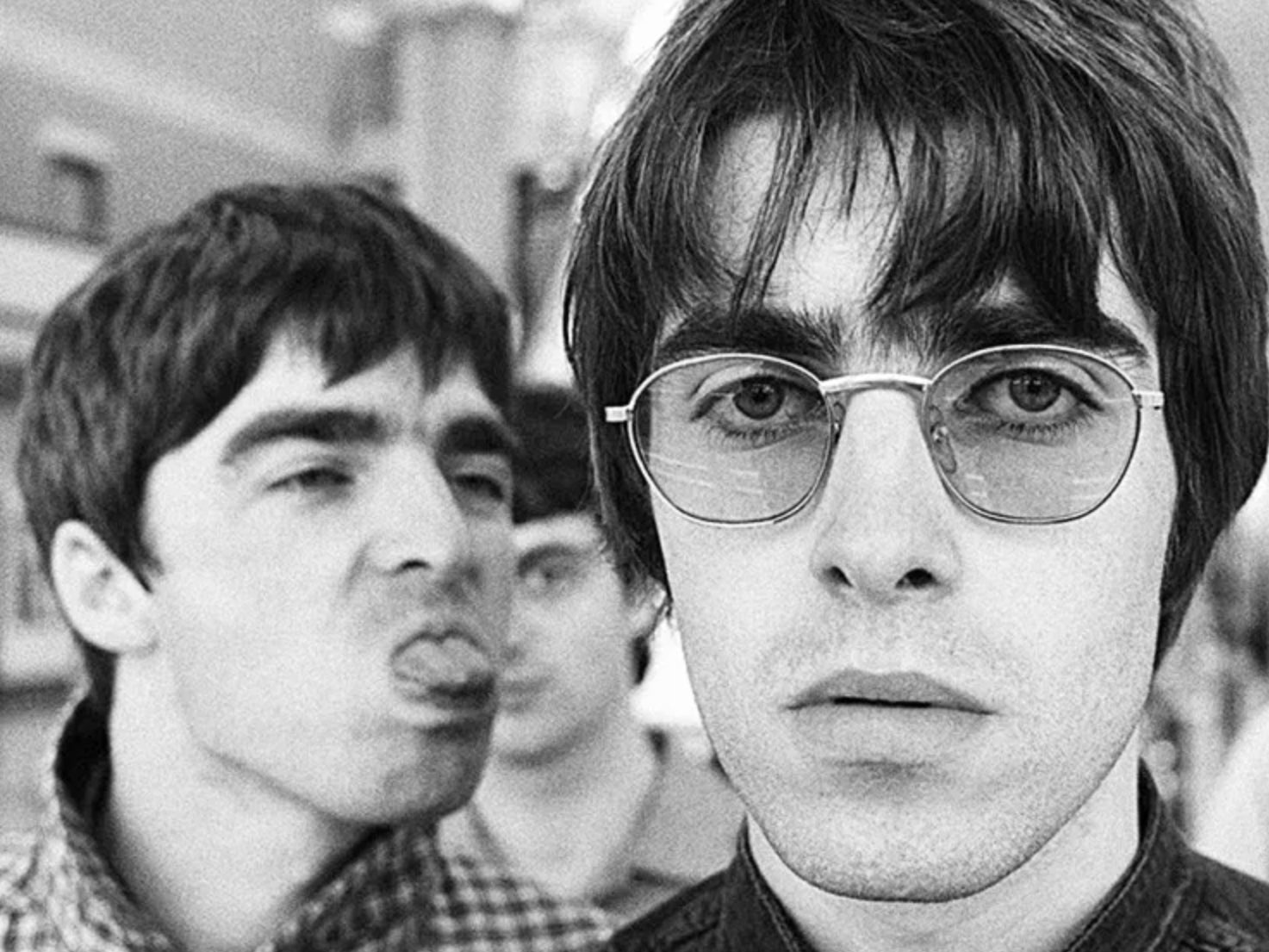

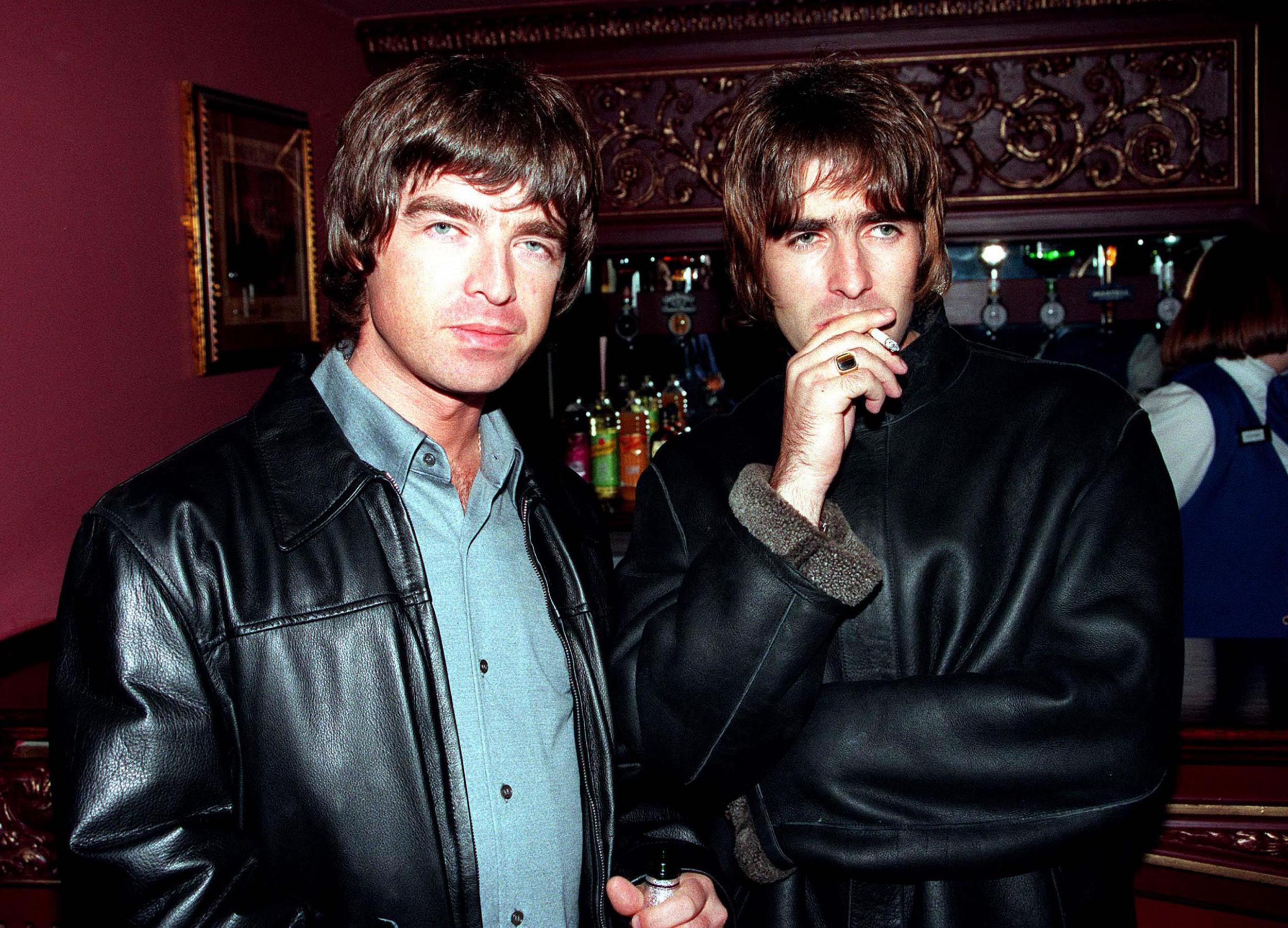

Finally, rock music’s biggest question mark has an answer as Oasis announce they will reunite for a 14-date tour next year, bringing an end to 15 years of intense feuding between Liam and Noel Gallagher. “The guns have fallen silent,” read the sibling’s joint statement announcing the news. But 30 years ago, back when the brothers’ exhilarating open warfare first broke out and swept the globe, it was all about the noise.

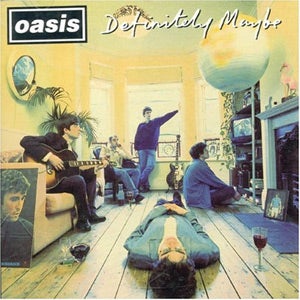

There’s a good few seconds at the start of Definitely Maybe, three decades old this week, where you might think you’ve put on an Eagles record. A very country riff strikes up over a grungy chunk of guitar, like a distant glimpse of the Californian dream – a sonic oasis, if you like. Ten seconds later, determined drums kick in, the guitar accelerates like a drag race to glory and a voice rises from the Manchester gutter, demanding the stars. “I live my life in the city, there’s no easy way out,” sang Liam as “Rock ‘N’ Roll Star” took flight, the ultimate example of manifesting one’s ambitions into cold, hard reality.

“The first line of that song is what my plan was,” Noel said in 2004’s Oasis: Definitely Maybe documentary, which looked back at the making of the seminal debut album. “I can’t wait to get out of this s***hole when I’ve made some f***ing money.”

He wouldn’t have to wait long. Before the album was even released Oasis were already bona fide stars thanks to the press hype frothing around early singles “Supersonic” and “Shakermaker”, as well as the Top 10 placing of “Live Forever”. And though 1995’s 23-million-selling second album (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? would be the record to make them global superstars, Definitely Maybe’s 100,000 first-week sales – en route to an eventual total of 15 million worldwide – made it the fastest-selling debut album in British history, and Oasis the phenomenon that ate Britpop for lunch.

At the time Alan McGee, co-owner of their label Creation – then £2m in debt – had far more modest ambitions for the record. “It was more like we could nick them in before the next Stone Roses album and maybe sell half a million copies and we’ll all have had a result,” he said in the documentary. “The idea was to get the record out to try to save a record company that was slowly going bankrupt.” Little did McGee know that his quick-buck Manc rock ploy would fast become a drawn-out and costly leap of faith – ultimately, though, a money-spinning behemoth of British rock culture.

Other classic Britpop records such as Blur’s Parklife or Pulp’s Different Class rival it for quality, but Definitely Maybe has aged significantly better, with still-elemental tracks such as “Columbia”, “Supersonic” and “Cigarettes & Alcohol” escaping the flimsy pop shackles of their era and entering the timeless rock realm. Liam’s recent arena tour, performing the album in full for its anniversary, was his finest solo outing yet, and its Reading & Leeds stop easily trumped his solo Knebworth 2022 show. Even the record’s backstory is legendary, involving drug-pilfering “ghosts”, acid freak-outs, magic guitars, and several blatant cocaine references that slipped right under Radio One’s nose.

As much as some of the lyrics about fish tanks and lasagne seemed thrown together last-minute after one too many drugged-up spins of “I Am the Walrus” – and in fact, the final verse of “Shakermaker” was written on the way to the studio, based on corner shops and traffic lights Noel saw out the car window – Definitely Maybe was no overnight phenomenon. Noel had been writing songs for up to five years while working as a roadie for Manchester indie heroes Inspiral Carpets and on breaks from his job signing out equipment for the gas board.

In contrast to the art school conceptualising, Kinksian whimsy, and chic cultural penchants of the emerging Britpop scene (Quadrophenia, The Italian Job, Performance), Noel’s songs were direct and unpretentious melodic throwbacks to The Beatles, The Who, David Bowie and TV ditties of his youth, drenched in heroic hedonism and brash emotions. “I wasn’t trying to impress anybody with my lyrical prowess,” he said. “I was writing about things that were true to me – shagging, drinking and taking drugs.”

When he caught wind that his younger brother and cock-about-town Liam had been recruited as a singer in a local Manchester band called The Rain – launched with little musical prowess by guitarist Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs, bassist Paul “Guigsy” McGuigan and drummer Tony McCarroll in 1991 – Noel turned up to rehearsals and insisted on being their guitarist and sole songwriter, transforming what Arthurs called their “racket with four tunes” almost overnight into a ready-made, amps-to-the-max, primal rock setlist. “I remember Noel coming in with ‘Shakermaker’,” said Arthurs. “I was just like, f***ing hell.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Multiplying like Fantasian brooms, Noel’s hefty cache of tunes allowed the formative Oasis – as they renamed themselves, after a venue on an Inspiral Carpets tour poster – to record 13 demo tracks at the studio of The Real People in the spring of 1993, having bonded with the Liverpool band over a 4am jam session. “With Liam looking like a star, and his attitude, even when we were working with them we weren’t saying if it happens… we were saying when it happens…” said The Real People’s Chris Griffiths.

Eight of those songs became the Live Demonstration demo tape, a copy of which was handed to McGee the night he famously caught the band when they forced their way onto the bill at Glasgow’s King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut that May, and offered to sign them on the spot. The more songs McGee heard, the keener he was to sign Oasis; he estimates that Noel had 50 tracks in the bag when they first met. “He used to lie and say he’d just written one on the train,” McGee said. “He had the first two albums.”

The volcanic demo version of “Columbia” was plucked straight from the tape and released as a limited-edition promo disc, garnering the band’s first attention from Radio One. Not bad for a song recorded in the 14th dimension. “All I remember about the night is that there was a lot of acid taken,” Noel said of the session. “Everyone was tripping in the studio and we did the demo that ended up getting about 50 plays on Radio One, all cabbaged beyond belief.”

The song – still probably the most powerful six minutes in Oasis’s oeuvre – had originally been their instrumental walk-on music, until The Real People suggested writing lyrics for it. From there, it became a tribute to the infamous rock’n’roll hotel that had been their regular London flop-house (the mad-fer-it cover of “Cigarettes and Alcohol” was shot there) until they were banned in 1994 for trashing the owner’s Mercedes from above.

An unpredictable group, tearing their way through the press with tales of cocaine breakfasts, brotherly scraps and their own unstoppable brilliance, Oasis still had plenty of spontaneity to offer on their debut album. At a demo session in Liverpool for its mooted first single, the estate-life Stooges tribute “Bring It on Down”, they couldn’t get the drums right; McCarroll would be shunted from the group before album two, despite McGee believing that “the punkiness of Tony McCaroll really did help that album” and Morris claiming “there was magic in the dumbness” of his primitive playing.

It sounded like a tame, major record company version of them rather than what they were

Alex McGee, owner of Creation label

Not wanting to return to Creation empty-handed, Noel disappeared into a back room with a fateful gin and tonic and came back half an hour later with “Supersonic” written in full. The famously nonsensical lyrics sprang off the top of his head, inspired by such on-hand influences as the BMW owned by Tony (brother of Chris) Griffiths and engineer Dave Scott’s flatulent rottweiler Elsa. “He just went, ‘There you f***ing go, ‘Supersonic,’” Liam recalled. The song was recorded that day at a cost of around £200 and presented to Creation as “our first single” in a fait accompli; the same demo version wound up on the finished album and gave Oasis their first Top 40 hit. “Why try and recreate genius?” Noel said of the decision not to re-record the track, which he described as “I Am the Walrus” of the Nineties.

When the album sessions did eventually begin with Kinks and Dr Feelgood producer David Batchelor at Monnow Valley studios in Wales in late 1993, classics were virtually dropping out of the air. Short of guitars, Noel asked his friend Johnny Marr to send some to the studio. “He sends down this Les Paul,” he said, “and I swear to you, I took it up to my bedroom, picked it out of the case, I sat down and [‘Slide Away’] wrote itself.”

If only the recording process had been so effortless. “It was a really difficult album to actually record,” McGee tells The Independent today. “On paper, it shouldn’t have been, because it was just a rock’n’roll band, but because it was Oasis, and I had seen astounding gigs before they went in to make that album, we knew the bar was really high.”

The Monnow Valley sessions, then, weren’t without incident. The Stone Roses were recording in the nearby Rockfield Studios and the two bands would sometimes hang out in their downtime, sharing drugs, road tales – and ghost stories. One night, high on mushrooms, Roses bassist Mani hotwired Rockfield’s tractor at 2am, drove to Oasis’s studio and broke in looking for alcohol. “Everyone was in bed, so I then went skulking round people’s rooms while they were asleep,” he told the documentary. “I spotted a big nugget of hashish by the side of somebody’s bed and I was reaching over to grab it and they were petrified because I’d given them this ghost story a few days earlier about the ghost of Monnow Valley.”

There was nothing supernatural about the recordings, however. Separated from one other in the studio, the Oasis chemistry dissipated and the dry, edge-free takes lacked their trademark roar. “It sounded like a tame, major record company version of them rather than what they were,” says McGee. Two weeks later, it was decided they’d scrap the entire session and start again. “I’ll always respect McGee for that,” Noel said. “He just said, ‘Go and do it again… you’ve got to get it right.’” McGee recalled the folly of putting Creation’s future on the line for the band, but still stumped up for another try: “I was a bit like, ‘I am scared but I’m not scared to the point that I won’t write a cheque.”

The second attempt at Definitely Maybe bottled Oasis’s raw lightning in just five days. With the band playing eye to eye in one room at Cornwall’s Sawmills Studio in January 1994 and their live sound engineer Mark Coyle now co-producing alongside Noel, the live magic instantly returned.

Admittedly, the recordings were still missing some heft, and with no chance of a third run at it, the tapes were sent to Welsh producer Owen Morris to mix into shape. Stripping away extraneous layers of guitar, and cutting Noel’s more Slash-like solos, he mixed the record in what he called a “brick-walling” style. “I’d be on the red line constantly,” he said. “There are no dynamics, it’s just full-on, all the way [and] it worked. On jukeboxes around the country that first year, Oasis would come on louder than everybody else.”

“Owen had never seen an [Oasis] gig,” says McGee. “God knows how he knew that was the sound of that band, but he absolutely nailed it.” And, when it did emerge – advertised in football magazines and match programmes as well as the music weeklies, and wrapped in striking cover art packed with personal references (Noel’s favourite Sergio Leone films on the TV; pictures of Burt Bacharach and Manchester City’s Rodney Marsh) – Definitely Maybe barged its way to the forefront of Britpop. Where Blur, Suede and Pulp were making wry, fantastic records of observational suburban culture, outsider pride and trash-poet romance, Oasis sounded like the unbreakable spirit of a Britain that Noel claimed was “in the toilet” post-Thatcher.

“Cigarettes & Alcohol” remains Britrock’s most air-punching celebration of breadline hedonism. “We’re the only band to get a song in the Top 10 that advocates cocaine use,” Noel claimed. A generational bravado found its voice on “Live Forever”, written partly in answer to Kurt Cobain’s “I Hate Myself and Want to Die”.

“This f***er, an extremely talented guy, had everything I wanted,” Noel told Blender in 2007. “He was rich, he was famous, he was in the greatest rock’n’roll band of its time, and he’s writing songs saying he hates himself and wants to die! My way of thinking was, well, I f***in’ love myself, and I’m gonna live forever, man.”

Even the relatively throwaway “Digsy’s Dinner”, the album’s most Blur-like song concerning the everyday joys of a lasagne supper, was a microwave-ready classic – although Digsy himself (Noel’s nickname for Smaller singer Peter Deary) actually hated the stuff. “I’m a pie and chips man,” he revealed in the documentary.

Within months, Oasis had exploded out of the tiny Manchester clubs into the major leagues, and the album shot to No 1. It seemed only the writers of The New Seekers’ “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (In Perfect Harmony)”, who sued the band over similarities between “Shakermaker” and their song, weren’t swept along in their slipstream.

“We seemed to catch the mood of the mid-Nineties,” Noel argued. “People always go on about the past being this magical, wonderful thing but that early period [of Oasis] really does seem like the last golden period for music.” The greatest debut album of all time? Maybe. What’s definite, though, is that when the reunion shows roll around next year, it will be this record’s visceral thrills, more than any blustery rock ballad of their later material, that truly capture the shock of Britpop’s brightest lightning.