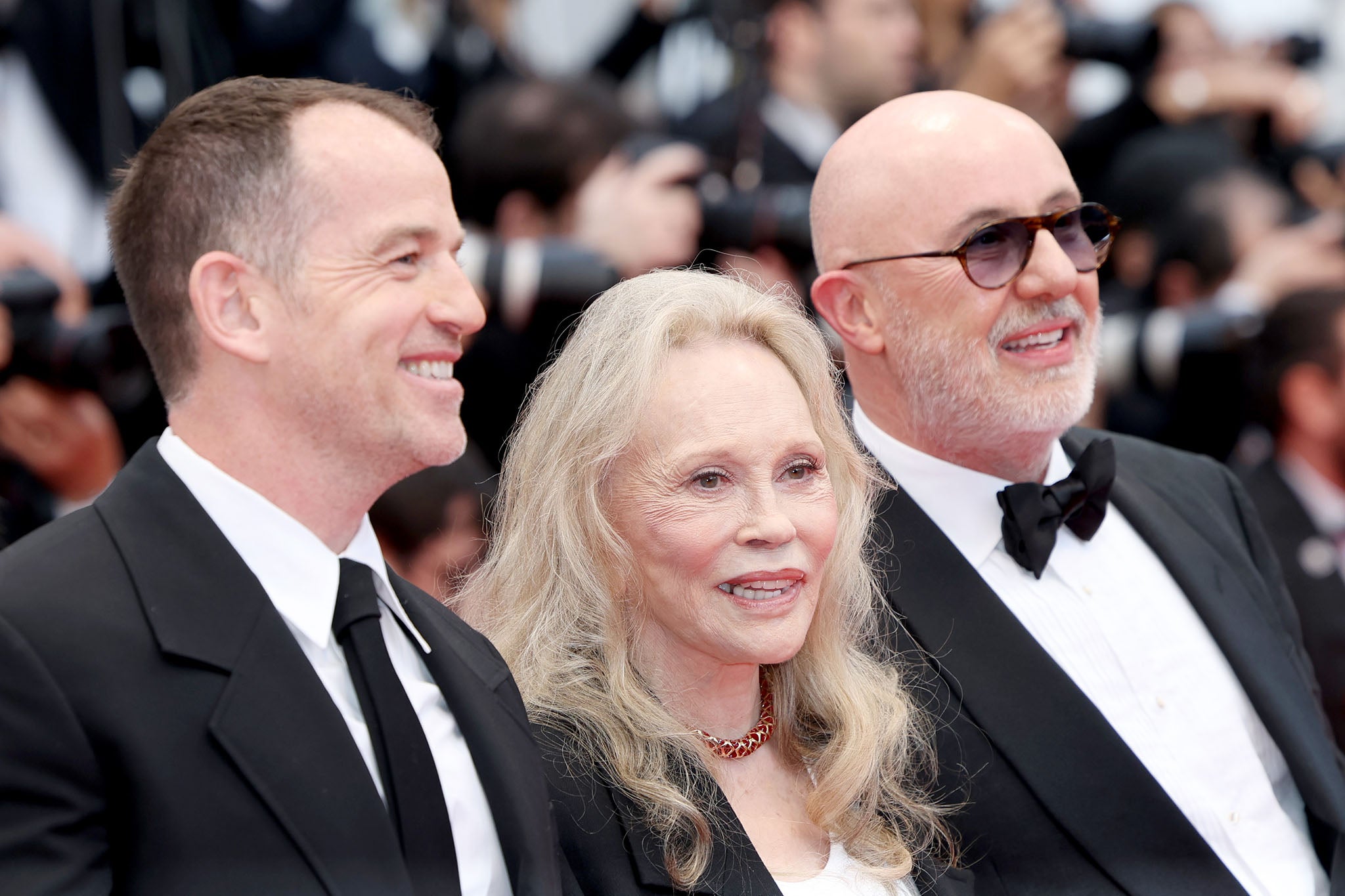

Emotion is a strength, not a weakness,” Faye Dunaway declares, as if it’s her pet mantra. The Oscar-winning star of Bonnie and Clyde and Network is sitting in a hotel in Cannes. Across the room is Liam Dunaway O’Neill, her son, with the British photographer Terry O’Neill, and alongside her is Laurent Bouzereau, the French-American filmmaker behind a new, revealing documentary about the star: Faye.

Dunaway credits the On the Waterfront director Elia Kazan – the man behind her 1969 film The Arrangement – with teaching her early on that she didn’t need to be ashamed of drawing on her rawest feelings in her work. It’s a technique that proved to be both her greatest asset and her biggest weakness. Bouzereau’s documentary may be fawning, but it deals very frankly with all those moments in which Dunaway’s emotions got out of hand and landed her in trouble.

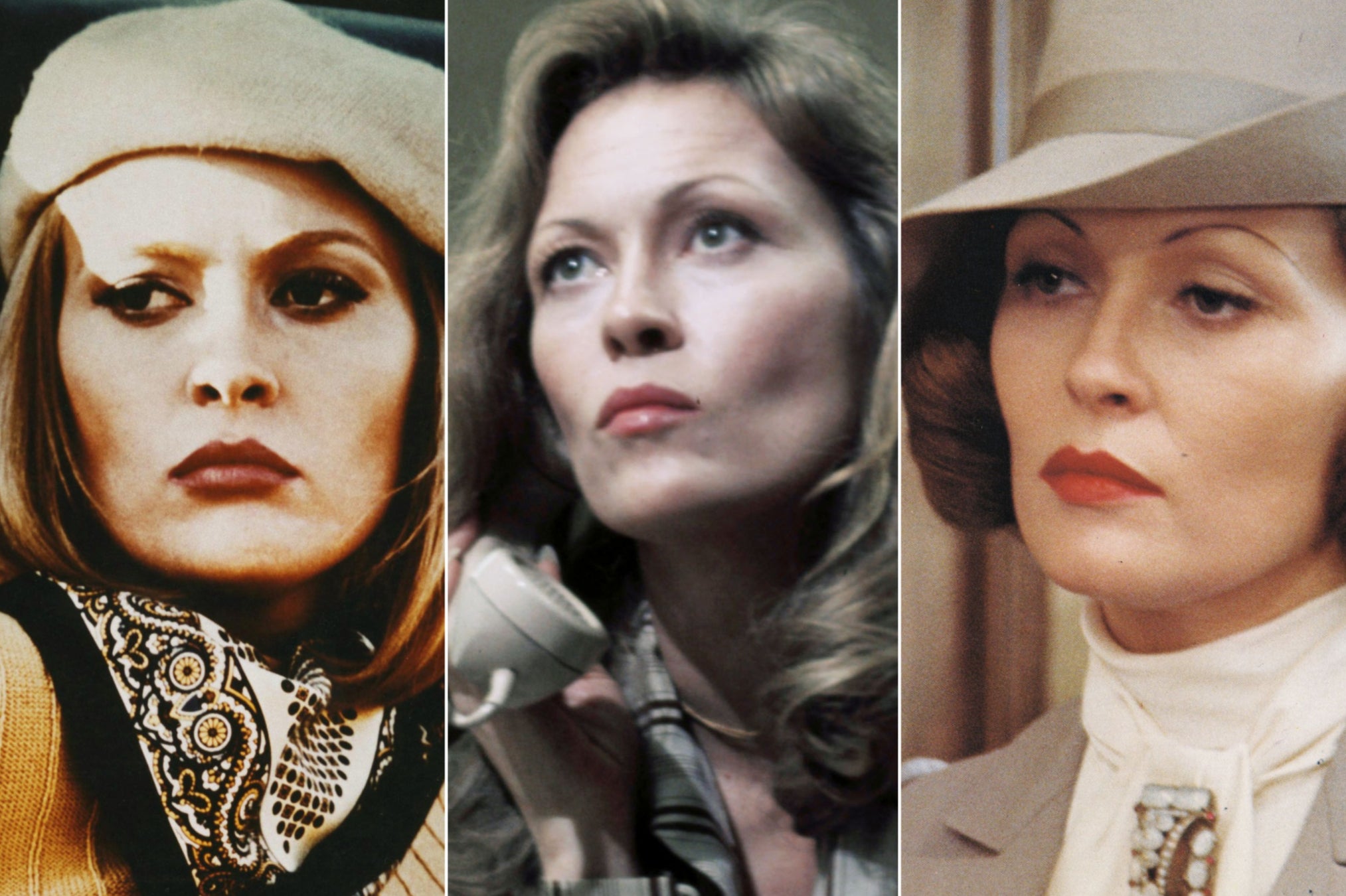

In the film, former collaborators openly call her “difficult”. We learn that Jack Nicholson nicknamed her “the dreaded Dunaway” – or “Dread” for short – on the set of Chinatown (1974), one of her most famous films. There is also an account of her famous feud with Chinatown’s director Roman Polanski. “Roman the terror”, she calls him today. The documentary includes the notorious clip from Johnny Carson’s chat show in which Bette Davis described Dunaway as one of the “worst people” she had ever worked with. It additionally addresses the catastrophic effect playing Joan Crawford had on her career – 1981’s Mommie Dearest is now a cult movie, but one that made her an object of ridicule upon release.

Looking back on those well-chronicled incidents where she lost her temper and berated colleagues, the now 83-year-old star cites her mental health as its root cause. “I actually have, we might as well say, a bipolar diagnosis,” Dunaway says. She talks in the documentary about consulting doctors who analysed her behaviour and ended up prescribing her medication that stabilised her violent mood swings.

The film, though, suggests that without her temperament, the Florida-born actor would never have been such a powerhouse on screen. When you watch her as the woman sexually abused by her own father in Chinatown, or as the obsessively driven TV exec in Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976), you realise that she is holding nothing back.

“The mania we tap into, and the sadness, of course… I don’t know how all that works exactly but I understand that I need all of that to use in my craft,” she says. “It has been a difficulty, of course, as a person sometimes. It’s something I’ve had to deal with and overcome and understand. It is something that is part of who I am, and that now I can understand and deal with much more.”

We wanted to tell a story that wasn’t a fluff piece, that wasn’t just all the good stuff. It had to encompass everything

Liam Dunaway O’Neill

Was the documentary cathartic? “Cathartic is a good word,” she replies. “It was. To look at it all and see what it added up to. It was difficult sometimes, because it is very private to me. I was a bit wary at seeing it all out there, but that’s the process – it’s the whole point of the film, the sharing of who I am. I dug deep!”

Another side of Dunaway’s story is the intense pressure she came under during the making of her best-known films. She was always expected to look immaculate. There would be little time to eat or rest between set-ups and it was hardly a surprise her nerves were on edge.

The documentary deals very openly with Dunaway’s resultant drinking: she had a love of gin martinis, which gradually tipped over into full-blown alcoholism. (She has been in Alcoholics Anonymous for 15 years now). It’s a disease that runs in her family. Dunaway’s father, who was in the military, also had severe drinking problems. One consequence of growing up as a soldier’s daughter was that she moved home every two years as her father received new postings. She believes this made her distrustful of long-term relationships.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“I learnt not to be too close to people because you’re going to lose them anyway,” she says in the documentary. It’s a remark made all the more poignant by her reflections on the romances that didn’t last. She calls the Italian movie star Marcello Mastroianni “in many ways the love of my life” – she had a fling with the married actor after working with him on the 1968 French-Italian romance, A Place for Lovers. Like so many of Dunaway’s relationships, it didn’t endure.

In the documentary, James Gray, who directed Dunaway in the crime drama The Yards (2000), pointedly claims that she’s been a victim of double standards and male chauvinism throughout her career. “Whatever reputation she had is also a comment on how women are in some ways treated and judged on a very different scale than men,” he says.

Nonetheless, when I ask Dunaway about the sexism she’s encountered over the years, she refuses to be drawn. “There are ups and downs,” is all she will say. “A career is a canvas. There are wonderful things. Then there are things that are less wonderful.”

Dunaway has endured her share of humiliations. Twenty years ago, it looked as if she would have an alternative career as a director. Her 2001 short film The Yellow Bird, adapted from a story by Tennessee Williams, premiered to favourable reviews at the Cannes Film Festival. “I liked that little story so much,” she remembers. “It was part of my past, [and] very connected with my southern background.” It revolved around a preacher’s daughter raised in conservative circumstances, but who “breaks out of her cage”.

But later, when she tried to write, direct and star in a film version of Master Class, a Terrence McNally play about the life of the opera singer Maria Callas – which Dunaway had appeared in on stage – it fell apart in disastrous fashion. The money ran out. The project had to be abandoned midway through. In the documentary, she remembers being “in pieces for quite some time, locked up in my room and going to analysis”, as if the failure was all her fault.

Interviewing the star with her director and son beside her isn’t an easy task. They are very solicitous and sometimes field questions intended for her. Bouzereau chips in with the observation that he has been on sets with “difficult” male actors making demands. “But that is never talked about,” he says. “If it’s a woman, it’s talked about. There definitely is sexism there, big time.”

He adds that male stars are able to withstand box office bombs in a way that women typically aren’t, referencing the 1987 disaster Ishtar. “That was worse than Mommie Dearest, but it didn’t destroy Dustin Hoffman or Warren Beatty,” he says. “But everybody wants to talk about freakin’ Mommie Dearest.” Dunaway chuckles at the observation with obvious approval.

Bouzereau tells me he didn’t want Faye to be “honey-coated”, that it had to have “that feeling of real life”. O’Neill chimes in, too, adding: “We wanted to tell a story that wasn’t a fluff piece, that wasn’t just all the good stuff. It had to encompass everything. My mom agreed because unless we talk about everything, it’s not the true story.”

He describes her as “a very strong woman… all of her characters in one in real life”. It’s an apt remark. Speaking to her, I realise that Dunaway approached the documentary in exactly the same way as any one of her acting assignments. That’s to say, she went all-in.

“I am very private,” she says. “Yet I shared everything.”

‘Faye’ is available on Sky Documentaries and Now from 18 August